In November last year, a friend of mine and her date were attacked on a London night bus by a man and two women who objected to them showing affection. The couple was beaten and left bruised and traumatised. Both had chunks of hair pulled from their heads, one suffered whiplash, one lost a small part of her scalp. You won’t have read about it in the papers.

The women, let’s call them Jill and Cathy, had been to meet up with some friends and then moved on to a bar in Baker Street before going out for a meal together and catching a bus back to South London.

The women, let’s call them Jill and Cathy, had been to meet up with some friends and then moved on to a bar in Baker Street before going out for a meal together and catching a bus back to South London.

“We had such a good night, “ recollects Jill. “It was so fun. we’d all been rolling around with laughter in the bar! I was really happy. It was such a good night.”

Cathy nods.

“And then we went for a meal in Chinatown. Cathy, you ate prawns even though you’re vegan!”

Jill laughs and Cathy rolls her eyes amiably.

“Yeah, and then we got a bus.” Jill’s tone becomes more sombre. “We got a nightbus from Charing Cross Road. And it was full, so we went upstairs, which I would never normally do…”

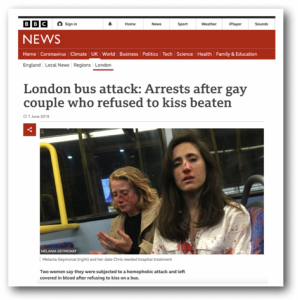

Melania & Chris

Before we move on with Jill & Cathy’s story, cast your mind back a few years. You may remember in 2019 when lesbian Melania Gaymonat and her bisexual partner Chris were attacked by a group of young males on a London bus.

Before we move on with Jill & Cathy’s story, cast your mind back a few years. You may remember in 2019 when lesbian Melania Gaymonat and her bisexual partner Chris were attacked by a group of young males on a London bus.

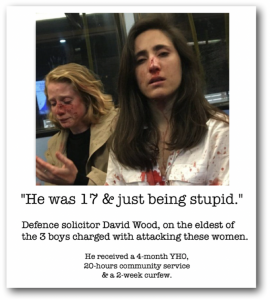

Like Jill and Cathy, they were attacked on the top deck of a London night bus. They were attacked for showing physical affection and left covered in blood after being punched and pelted with coins.

Then-Prime Minister Therea May called it a ‘sickening attack’ and Jeremy Corbyn and other politicians jumped in to tweet their support of the LGBTQ+ community in general.

The photo of the bleeding women was all over social media and the press.

The country was indignant, shocked and horrified.

But was it really?

“He was seventeen and just being stupid.”

The eldest of their attackers was sentenced, later that year, to a four-month youth rehabilitation order, 20-hours community service, and a two-week curfew.

The eldest of their attackers was sentenced, later that year, to a four-month youth rehabilitation order, 20-hours community service, and a two-week curfew.

“He was 17 and just being stupid,” his defence solicitor said.

A sixteen year old involved in the attack, who also stole from the women, received an 8 month YRO and a £100 fine.

A fifteen year old was ordered to attend ‘diversity sessions’.

“It is clearly a case of immaturity and stupidity rather than hostility.” claimed his defence.

Of course, we all know these sentences are not really surprising. We live in a culture where violence against women is repeatedly excused and glossed over.

From women judged complicit in their own deaths in ‘sex games gone wrong‘ to women jailed for killing their rapists (USA), to women made to refer to the man who attacked them in court as ‘she’, we are repeatedly shown how unimportant attacks against us really are in the eyes of the law.

Chris later wrote an article for the Guardian in which she claimed that the case only got attention because ‘we’re white, feminine and cisgender’. The article is thought-provoking and I would certainly agree that the photograph of the young, bleeding women captured the imagination of the nation. Chris’s article is a frenzy of apology for her own prettiness and white privilege and how it has evidently helped her ‘evade much of the violence and oppression imposed on so many others’.

Her bloodied and bruised face in the photos might suggest otherwise.

Women- even articulate, outspoken ones- are trained to be complicit in our own silencing. Women will frequently find excuses for men’s violent behaviour and reasons not to hold them accountable. I have done it myself. The endless speculation about the race of the boys that attacked Chris & Melania strikes me as a distraction from the issues in hand, which in this case are not how pale or pretty the women were, or what colour skin their assailants had, but male violence, misogyny and lesbophobia.

Reactions to trauma

Like Jill and Cathy, Melania and Chris were not entirely clear about the exact words in the verbal exchange which took place before the assault, but both groups of women were clear that sexual comments were involved.

“They wanted us to show them how lesbians have sex.” Melania told the press. “They said ‘show us’ and I don’t remember if it was on its own or part of a larger phrase but the words were said.”

“My memories of the fight are addled by adrenaline. Maddeningly, I don’t remember exactly how it started.” reported Chris.

“I can’t say verbatim,” Cathy, who is bisexual, told me of the attack on her and Jill, “but they were asking us about our relationship and our sexuality. And the girl- the blonde girl- I remember was just disgusted. I just remember her face. I don’t remember what she said. But I remember the tone of her voice and her facial expression.”

During a traumatic event, the neurotransmitter norepinephrine is released and it allows the brain to ‘zoom in’ on some things and tune out others. The brain then stores clear details of some aspects of events and brushes others aside.

During a traumatic event, the neurotransmitter norepinephrine is released and it allows the brain to ‘zoom in’ on some things and tune out others. The brain then stores clear details of some aspects of events and brushes others aside.

“You can think of it like turning up the contrast on your TV,” says Charan Ranganath, director of the Memory and Plasticity Program at the University of California. “If the contrast is low, you can see everything, even though some things are brighter than others. But if you crank up the contrast, what you’ll find is that some things are super bright and everything else is kind of hard to see.”

Cathy & Jill

The downstairs of their bus being full, Cathy and Jill went and sat upstairs at the back. Cathy had her back to them, but Jill noticed a group sitting across the back seats.

“The male was definitely young because I just seem to remember him having like a shadow here,” she gestures to her lip, “like, not a real moustache. Like his moustache was just coming in. He was using that gas, you know, those gas canisters and I remember,” she grimaces, “he was blowing up a balloon with it. So it was quite a sight. It’s kind of bizarre because you know, they’re, like, childish brightly-coloured balloons and they’re used to do this nasty stuff.”

“The male was definitely young because I just seem to remember him having like a shadow here,” she gestures to her lip, “like, not a real moustache. Like his moustache was just coming in. He was using that gas, you know, those gas canisters and I remember,” she grimaces, “he was blowing up a balloon with it. So it was quite a sight. It’s kind of bizarre because you know, they’re, like, childish brightly-coloured balloons and they’re used to do this nasty stuff.”

Jill felt the man was invading the space of the blonde woman he was with, so gestured to her, ‘are you ok?’ and the woman nodded. The man with the tiny tash & the balloon didn’t like this interaction and growled something along the lines of, “mind your own fucking business”.

His response, recalls Cathy, was, “the first sign of menace.”

Cathy and Jill looked away and engaged in conversation together for a few minutes, before kissing briefly.

“I could see over Cathy’s shoulder, that girl with the blonde hair saw us, and her face was just- disgust.. and it definitely was, you know… us being affectionate was definitely the trigger.”

Neither of the women can remember exactly what was said. The blonde woman looked repulsed, they recall, but the man seemed more- interested. He leered at them and asked if they were girlfriends.

“He asked something like ‘what are you?’ and ‘are you two girlfriends or what?’ I think we called him a creep. We were obviously pissed off with that.”

“I wasn’t really paying attention before,” said Cathy. “Then the threat level went up a bit.”

She is unsure of exactly what she heard or saw, but suddenly found herself saying to Jill, “We need to get off and we need to get off now!”

Cathy moved quickly towards the stairs.

“…and that’s when the guy ran after me and tried to shove me down the stairs. And then I heard Jill screaming and that’s when I went back up and fought my way through him. I thought there were about four or five people! But when you’re in that moment it’s pure adrenaline and I was just thinking ‘I’ve got to get Jill out of this situation and get out of there.’ I remember punches being thrown… I just have flashes of what happened. Apparently that’s quite normal. When you’re running on adrenaline your brain just doesn’t function. Your body takes over.”

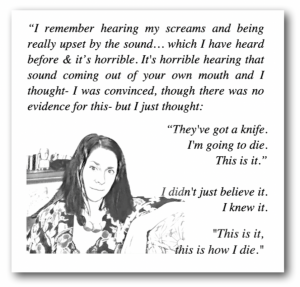

“When they landed on me,” Jill relates, “they grabbed my hair and I just remember how my head pulled back. It was really painful: it’s a horrible, vulnerable feeling because they’re in control, they’re in complete control of your head and it’s a horrible feeling. So I pulled hard to get my hair back off of them. And then I remember hearing my own screams…”

Jill threw herself into a double seat with her back against the window and kicked out hard and repeatedly at her attackers while trying to protect her body and head.

“There was a man in the seat directly behind me but because I was turned in my seat kicking he was on my right, if that makes sense, and he just sat there. I remember screaming at him, ‘Why are you doing nothing? Why are you doing nothing?’

In that moment I just couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that this was happening and no-one was doing anything. It really hurt me to my core. He didn’t speak to me or reach for me, even though he could have put his arm around me with little stretching. I’ll never forget that.”

Cathy remembers trying to fight them off in an attempt to get to Jill and pull her free.

Neither Jill nor Cathy are certain how much time passed before some women from the lower deck came up the stairs to help them and the assailants fled downstairs. Some other passengers tried to stop the attackers leaving the bus and called 999.

“There were several 999 calls made,” Cathy told me.

Jill and Cathy were helped off the bus by the women who had come to their aid. The driver however, who will have been able to view the attack on his live CCTV and who will have heard Jill’s screams, closed the doors and Jill recalls that he was about to drive away.

“I heard the sound of the bus doors closing and I banged on the cab and was sort of howling, sobbing, shouting at the driver. I remember being so upset and outraged. It was as if what happened was completely irrelevant to the driver who just wanted to keep going.”

The bus didn’t pull away and the three women who had intervened stayed with Jill and Cathy until the police arrived, hugging them, reassuring them and even going to a nearby shop to buy them bottles of water and tissues.

The evening after I spoke to Cathy and Jill about the attack, Jill sent me this message.

“When the attack was happening and no one was helping us and there were grown men all around us doing nothing I felt despair. When the attackers ran off the bus and we had help and the help came in the form of women it was a tonic. I mean, on the one hand it’s disgusting that the men, who had the physical advantage to help us, did nothing: but I’ll never forget the women who got off the bus with us. They recognised misogyny and homophobia when they saw it. They gave witness statements, backed up everything we were saying, and spoke with an anger, outrage and disbelief that mirrored my own.”

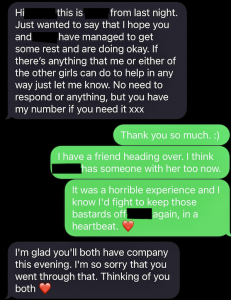

Cathy showed me a text she received from one of the women the next day.

Cathy showed me a text she received from one of the women the next day.

“Hi, this is —— from last night. Just wanted to say that I hope you and (Jill) have manged to get some rest and are doing okay. If there’s anything that me or either of the other girls can do to help in any way just let me know… you have my number if you need it… I’m so sorry you went through that. Thinking of you both <3”

The police

Cathy remembers the police arriving very quickly.

“The female officer was lovely, I liked her.”

“The female officer was lovely, I liked her.”

“The male officer was really annoying and very unsympathetic,” reflects Jill. “The first thing he said was something along the lines of ‘have you been drinking?’ or ‘how much have you had to drink?’ or something like that. I mean, that’s not the first thing you asked two women who’ve just been attacked! I remember telling him in no uncertain terms I didn’t want him anywhere near me. “

The officers took statements from Jill, Cathy and the witnesses and then drove the two women back to Jill’s flat.

Jill and Cathy had decided not to discuss the attack too much among themselves before giving their full statements to the police, whch happened a week or two later. The police interview process was thorough: it took over three hours for Jill’s statement to be recorded. By the time of our chat, both had given their statements and had had time to discuss it together.

A few days before our meeting, Cathy heard from the officer in change of the case that all witness statements had been received, and the CCTV report, and that stills from the CCTV footage had been issued to police departments. He read her the CCTV report and assured her that the three attackers have had their photos circulated amongst 33,000 police officers.

Cathy, who had her back to the attackers for most of the journey, was deeply distrubed by her inability to remember how many attackers there had been. She had remembered there being at least two more.

“It made me feel like I was going mad!” she told us. “It troubles me that my memories don’t align with what he told me the CCTV footage showed.”

“But we didn’t know we were going to be attacked for no reason!” Jill reassured her. “It’s not our fault. No one should have to go around committing every single thing to memory on the off chance that they’re going to have to tell it to a police officer one day. We did nothing wrong. We didn’t attack anyone. We didn’t commit any crime or any violent acts. They did: only them.

The police officer said that it doesn’t matter that we don’t remember stuff because it’s all on CCTV. He said there’s no dispute about what happened; he said it doesn’t matter even if you didn’t remember a single thing; it’s all there, they know what happened.”

The attackers

I ask Jill and Cathy about their attackers and they described to me what they could recall of them.

“He must have been a good six footer,” remembers Cathy, “because I’m tall and I had heels on and he was a good couple of inches taller than me. He was tall, very white, and I think he had closely shaven hair if not a shaved head and, I said to the police, I think I want to say that he had a blue jacket on? But he was so, just like… average.”

“He was pale. Almost see-through.” adds Jill. “As if he’d never eaten a vegetable in his life. I think he wore sportswear or a tracksuit, and I remember blue. I think there was a cap. And that tiny moustache.”

“One of the women was black, or south Asian maybe. She had dark skin and black hair. Medium height and build, I think. I don’t remember much about what she was wearing, she was further away from us when I was facing them and I was focusing more on the male, who was the threat.”

“I didn’t notice the women as much either. They were quite small, I think.”

“The female who was behind us, she was white, she had badly-dyed blonde hair, I think it was long. Lots of make-up and I think a puffa jacket.”

“Yes, really badly-dyed blonde hair- not that I can talk! – an orangey-yellow colour.”

Cathy would place them all in their mid-twenties, Jill thought they were a little younger.

“A lot of the stuff I remember about them was so, you know, changeable. I don’t know if I’d recognise them again. Especially individually. One can change the colour of one’s hair; one can grow hair or cut it. You can, you know, take your makeup off. These things can make a big difference.”

Injuries

Both women were left with bruises. Cathy is less forthcoming and more stoic about her injuries but is clearly traumatised by the experience. Jill got the worst of it, Cathy says, but she still showed me a bald patch on her head where part of her scalp had been pulled out along with her hair. Cathy didn’t see a doctor but has suffered with flashbacks and insomnia and has not been on a bus since the attack.

Large chunks of Jill’s hair had been pulled out, and as well as whiplash she had bruising along her back and hips where she had been pressed up against the window.

“For me the pain was really bad in my neck, and I was getting referred pain going down both my arm. The doctor said having your head pulled back like that, and then pulling it in and back again, can cause whiplash. She said it sounded like classic whiplash and prescribed me codeine for the pain. My neck and shoulder pain lasted about six weeks with me taking codeine for about three of those weeks. My scalp, where they tore my hair out, stung for about four days. It was really tender ;I couldn’t brush my hair or wash it.

I had a really bad period of insommnia. Really bad. It was worst for about two weeks. When you’re really tired you’re just not as robust as you’d like to be so just everything’s bit harder.”

Does she go on the bus now?

“I have hopped on a bus for just one or two stops if I’ve got heavy bags but only if it’s four o’clock or something: not at night time. I’ll never go upstairs, ever, never again. I need to be near the door.

I was standing near the bus stop recently and that bus pulled up. It was like it was cold calling, you know, I looked and I saw the number on the front and my stomach just went: I thought I was going to lose my lunch. I thought wow, I didn’t expect such a strong reaction. When I see buses at night now, that horrible blue light; that horrible cold lightless inside- that gives me shivers in the way that a bus in the daytime doesn’t.”

Catching the bad guys: don’t hold your breath.

This all sounds very positive until you realise that police officers are confronted with scores of new photos every day when they arrive at the station. And despite telling Cathy that the CCTV footage is ‘incredibly clear’ there are no police plans to release it to the public.

The attackers did not swipe their Oyster cards on boarding the bus, so are untraceable. Without a media storm it is seeming less and less likely with each passing day that the attackers will be caught.

The women were told that this decision is normal: photos and footage aren’t usually circulated among the public except in extreme cases. But that isn’t entirely true. CCTV footage from the bus was circulated after the attack on Chris and Melania. So why not this time?

As Chris acknowledges, Melania and Chris were photographed immediately following their attack and the pictures were circulated on social media. Without photos of the incident to capture the eyes of the press, it has not picked up on Jill and Cathy’s story. Without the attention of the press, perhaps it isn’t so important for the police to be seen to be doing something.

And if the attackers are caught, what happens next?

They’ll be told off for ‘being stupid’ or reassured that they had been acting with ‘immaturity and stupidity rather than hostility‘.

Naughty children. Try not to do it again.

This is a large part of my anger. I’m not suggesting that we lock away angry children or young people and throw away the key. We need fewer people in prisons, not more. I am suggesting that writing off such attacks as down to stupidity or immaurity helps nobody. It certainly doesn’t help to teach the perpetrators that violence is unacceptable.

As for the message it gives to lesbian and bi women who may wish to express physical affection- a mere kiss- in public, the message is far darker. Politicians may be happy to use you to signal their support to the LGBTQIA2+ ‘community’ but the judiciary, basically, doesn’t give a shit.

“How many people go missing each day, yet never appear on a milk carton? Who decides which missing child is important or which murdered woman makes the newspapers?”

“How many people go missing each day, yet never appear on a milk carton? Who decides which missing child is important or which murdered woman makes the newspapers?”

Jill reflects that there’s a lot of work for an already overstretched police force involved in circulating photos: someone has to collect the screenshots, crop them, publish them, write the copy, distribute them…

“…and if they were doing it for everyone it would take hundreds of hours, I suppose,” she says doubtfully.

Yet the police seem to have plenty of time on their hands for checking people’s thinking and investigating non-crime hate crimes.

Time enough for chasing and arresting women who might or might not have tied ribbons near a man’s place of work and posted photos of them on social media, or who tweet about farmyard animals in fake hairpieces.

Time enough for chasing and arresting women who might or might not have tied ribbons near a man’s place of work and posted photos of them on social media, or who tweet about farmyard animals in fake hairpieces.

There’s plenty of money to wrap police cars in rainbow colours, send officers for diversity training and issue them with LGBTQ+ lapel badges.

In 2020 the Scottish Sun reported thast UK police forces had spent over £90,000 on Pride-styled pens, lanyards and stickers.

The police are certainly very keen to be seen to be LGBTQIA+ friendly.

Finally

The two attacks in London that I write about here are, of course, not isolated events.

The two attacks in London that I write about here are, of course, not isolated events.

In 2016 a man called Sazi Tutani, who had been taking cocaine, called Allessandra Field and her wife ‘fat dykes’ and assaulted both of them on a London street. Field reported that she was left scared to leave the house. The man was caught, but left the country and did not return for his trial.

In the same month Cathy and Jill were attacked, in London’s West End, a woman told a man who was hassling her that her companion was her girlfirend. He called them a lesbophobic slur and punched her so hard she spent several days in hospital with a broken jaw. Photographs of him were made public but (as far as I can tell) he has not been caught.

Later in 2019, shortly after Chris and Melania were attacked, two women in Southampton had stones thrown at them from a moving car for kissing in public. A newspaper article about the attack was later ammended to use ‘they’ pronouns to refer to one of the women.

But attackers are unlikely to ask for your preferred pronouns or induldge in a discussion about your gender identity before assaulting you.

The police might do well to reflect on this when they eventually file away the unsolved case of an assault on two women who dared to kiss on a bus.