The third- and hopefully final- part of ITV’s mini-drama Butterfly hit our screens tonight.

(See also my reviews of episodes 1 and 2)

Although Vicky hasn’t made time to phone Stephen or Lily, Max has posted a selfie of himself and his mum on social media with the tag ‘Boston’.

Although Vicky hasn’t made time to phone Stephen or Lily, Max has posted a selfie of himself and his mum on social media with the tag ‘Boston’.

Stephen is understandably miffed.

“She’s going to get treatment for Maxine. Is that wrong?” asks Grandad, rhetorically.

“It makes her a crap mother!” sulks Stephen, adding, “This should’ve been our decision.”

“But if Maxine was desperate for it to happen…” continues grandad and I wonder if he would have maintained such enthusiasm had Max really, really wanted a tattoo.

Cut to the pristine glass and neon hospital where Dr Farrell appears like a genie, waving a greeting to Vicky and Max, by a big glass elevator.

“Turn into, transform, become, blah blah blah,” he waves his hand with a worrying lack of eloquence, or interest in the method of the wheels he’s about to set in motion.

“Turn into, transform, become, blah blah blah,” he waves his hand with a worrying lack of eloquence, or interest in the method of the wheels he’s about to set in motion.

“Let me ask you a question, Maxine. Are you a caterpillar that wants to turn into a butterfly?”

“I’ve always been a butterfly.” says Max.

“Yes you have, by God, yes you have! Ok, now here’s the thing. I’m not a paediatric, endocrinologist, transgender doctor,” he chortles, leaving me wondering for a minute if they’ve bumped into a particularly quirky patient by mistake. “I’m someone who helps children give birth to themselves. It’s so rewarding.”

So rewarding. I half expect him to whip a lollypop out from behind his ear and trot laughing all the way to the bank.

The most expensive parts of this treatment, Doctor Lollypop tells Vicky, is the psychological assessment. He adds that this part won’t be necessary if they have a confirmed diagnosis. Vicky shakes her head. “A letter from a gender expert?” he enquires. Still no. “Documentation from a school councillor or therapist?” he tries again, hopefully. Would he actually have provided puberty blockers on the sayso of a school councillor? Surely not- but we don’t find out, because Vicky, who has already forged Stephen’s signature on the consent form, agrees to pay for the hospital to do the tests.

“It’s all sounds very invasive, but it’s not,” says the doctor, reassuring her that she doesn’t have to pay for it all once. Of course, depending on how far down the path Max eventually goes, the process could end up being very invasive indeed.

It’s my baby’s only chance, so…” says Vicky solemnly, once again reinforcing the notion that Max’s options are transition or die. “I’ll do whatever it takes.”

In the montage that follows, less than a couple of seconds covers the psychological counselling. The viewer accompanies Max along a trail of blood tests, examinations by various important and expensive looking machines, body scans and Xrays, all giving the impression that some sort of grueling physical diagnosis is taking place. These will be the standard tests to ascertain Max’s physical health of course, not the psychological tests mentioned by the doctor, but the casual viewer could be forgiven for thinking that some official scientific ‘gender confirming’ process is taking place. I half expect Doctor Lollypop to pop up saying “By Jove, we’ve found it! He does have a pink brain after all!”

Back home, Lily is sad. “I know I’ve never had as much attention as Maxine,” she tells her dad. “I’ve never been a problem. It’s all about Maxine.”

Her phone rings, she throws it to Stephen who answers. Cut to Vicky who hangs up. The camera pans round to focus on Max who is standing by a fountain of cascading water and golden mermaids.

Of course Lily is right. It is indeed all about Max. Her dad proves this by crying in the bathroom until she forgives and consoles him, then dumping her at her gran’s house to make chocolate cake.

“What are you going to do?” asks Lily, as her dad drives off to file charges against her mum at the police station. There he’s told that Vicky’s actions can be classified as parental child abduction.

“Do you really want to pursue a criminal case against her?” asks the police officer. Stephen, moody and silent, does not answer.

Cut to Boston. Dr Lollypop tells Max he’ll see him in three months. Next stop the airport. As Max and Vicky arrive back in England, we see Stephen flexing his excellent parenting skills by turning up to watch Max being dragged away as Vicky is arrested under Section 1of the Child Abduction Act.

Cut to Boston. Dr Lollypop tells Max he’ll see him in three months. Next stop the airport. As Max and Vicky arrive back in England, we see Stephen flexing his excellent parenting skills by turning up to watch Max being dragged away as Vicky is arrested under Section 1of the Child Abduction Act.

Vicky is told by the police that if she takes Max abroad again she’ll be reoffending.

“Is she going to jail?” asks a perfectly coiffed Max, seeming entirely unruffled by the experience.

“She knows how much it matters to me.” he explains, adding ominously, “She doesn’t want me to get suicidal. .. She’s just trying to help me become what I am.”

Lily, grandma and dad are at the front door, looking sour-faced, when Vicky and Max arrive home.

“You think you’re a great mother, don’t you Vicky?” sneers Dad of the Year, dismissing further trips to Boston as impractical.

“Being in the wrong body’s impractical,” mutters Vicky, in the second most excruciatingly gauche line in this episode. “You can punish me but please don’t punish her.”

“You and Maxine, you both lied to me, you both went off together.” accuses Lily.

“It wasn’t about you.” replies Vicky.

“I hate you both,” retorts Lily.

“You saw what she did to herself and you didn’t do anything,” cries Vicky to Stephen, her arm tight around Max.

Weighed down by accusations, Stephen walks out on his family yet again, goes to stay with his dad and starts stalking ex-girlfriend Gemma.

Vicky’s solicitor tells her that the police and the school have already made referrals to the local authority. Her solicitor, like everyone else in this episode, has no problem using the name ‘Maxine’ and female pronouns when referring to this confused little boy. She tells Vicky she might get an interim care order if they think Max is at risk of significant harm or emotional abuse.

“What do you want most in the entire world?” an impassioned Vicky asks Max, who replies,‘To go back to Boston.”

Vicky tells Max that if he takes blockers, ‘everyone else at school.. Molly.. will be changing and developing. You won’t, you’ll stay the same for three years. Are you okay with that?”

Max, unsurprisingly, considering the alternatives that are expected of him, concedes.

“If it stops me becoming more of a boy it will be worth it, won’t it?”

Vicky smiles.

Max’s friend Molly, the girl used in episode two to push the idea that while anorexia is an illness, gender dysphoria isn’t, is unlikely to be developing at any time in the near future. She has been hospitalised again for her anorexia. Later in the episode, Max visits her. He keeps his distance, perched at the end of her bed.

“Don’t give up, Molly, don’t give in to it. Get better.” he advises her, calmly.

“You’re so strong,” she breathes.

Max looks away.

Dad of the Year catches Gemma while she’s out for a run.

“I don’t have anyone else to talk to,” he moans. Gemma is not impressed.

Stephen tells Vicky he’s withdrawn his statement concerning her abduction of Max. Vicky is not very impressed either. She scoffs at his idea of going back to Ferrybank to talk about things further.

“She needs her puberty suspended otherwise she’s going to get more sick. I’ve already told you that. God knows what she’ll do!”

“I’m not going to listen to emotional blackmail,” retorts Stephen, perhaps the most sensible thing he’s said all episode.

As she starts out for the school run, the postman hands Vicky an envelope containing a care order for Max and prohibiting further trips abroad.

The document blithely refers to Max as Maxine and uses female pronouns to refer to him, despite a court order being an official document and the child concerned being legally and biologically a boy. Remember, Max still doesn’t even have his official diagnosis. Would a court really do this on nothing more than the sayso of the very person they were serving with a care order? The very person or people they suspected might not have a child’s best interests at heart? I wonder.

The Guardian arrives at the Duffy home. She tells them she’ll have to write a report and observe the family.

Max shows the Guardian his bedroom, a plethora of pink, My Little Pony, feather boas and fairy wings, inspired he tells her, by his sister and Zoella.

“Very grown up,” she lies.

“What did you expect,” sneers Max, as he moves past a poster of Little Mix. “Pictures of Harry Styles?”

“Selfish bitch,” shouts Lily, talking to the Guardian on the way to school. She is evidently talking about Max.

“Bitch?” accuses the Guardian, “Your own sister?”

“Yes, my sister!”

Poor Lily. Nobody cares what she thinks.

There’s no doubt that his mother loves him, but is anyone genuinely looking out for Max, really looking for him; trying to see the little boy that lies under the make up and his mother’s constant assertion that his options are transition or die?

When the series began I expected the writer to at least give lip service to the idea that someone – just one- of the cast might have a calm, gentle, loving chat with Max about the fact that he actually might be a boy after all, but no, not even that.

The Guardian continues to observe and assimilate.

Vicky bitches about Stephen. “He’s a coward.”

Stephen bitches about Vicky. “She’s reckless, irresponsible, obsessed.”

“There’s no sign any boy ever lived in here,” Max tells her, serenely, wearing a darker than usual shade of lipstick.

“Where’s Max now then?” asks the Guardian, curiously.

“Max is in here.” he says, showing her the suitcase of ‘boy things’ still stored under his bed.

“Is he? But weren’t you always a girl anyway?” she asks.

“I don’t know.”

“What do you think Maxine wants?” the Guardian asks Vicky.

“Isn’t that obvious? She wants to be a girl.”

Max tells Stephen over breakfast how great things are going to be in Boston, anticipating a heady combination of chats with Doctor Lollypop, puberty blockers and sightseeing. Stephen, angry that Vicky hasn’t told Max this won’t be possible, goes snitching to the Guardian, who is not impressed.

“You’ve made promises to Maxine that you just can’t keep.” she accuses Vicky. “It’s emotional abuse.”

“It’s Stephen who abused her,” retorts Vicky. “He hit her.”

“I’ve seen enough.” The Guardian leaves and all is not well in the House of Duffy.

In third place for ‘most awkward and contrived line in the episode’ comes Lily’s next offering to Vicky.

“You’ve just been running round like you’ve only got one daughter.”

Gemma bumps into Vicky in the mall while Lily and Max are trying on clothes and introduces herself.

“Maxine’s a beautiful looking girl,” says Gemma. ”She’s a beautiful girl full stop… look how she just marches into the changing room, and why shouldn’t she?”

You guessed it, that line gets first place.

Vicky is down by the canal path. Sunlight dances in her hair and meditation music plays. Stephen arrives. They giggle as the sunlight glistens on the water.

“You’re still funny,” she tells him.

“I’m still here,” he says, although we do wonder if that would be the case if things had gone better with Gemma at their last meeting.

United in their rekindled love, Vicky & Stephen go back to Mermaids.

“How can we tell her she can’t go back to Boston? It’s basically her only hope,” observes the ever-optimistic Vicky.

“Go back to the clinic, make them change their minds.” advises Alice.

The family are immediately inspired and determined. Max and Stephen hug.

“Only girls hug you like this.” says Stephen. “Only daughters.”

But wait, there’s trouble afoot! The Guardian tells them she’s going to recommend a care order made and Max could be removed from the family home. She’s also going to recommend the court prohibits treatment. All seems lost. Unless… but wait! It seems that there is hope after all! Only a positive outcome from a visit to the Ferrybank Clinic can save the family now.

“If the Ferrybank say it’s for the best we wouldn’t stand in the way of her treatment.” offers the Guardian.

Max’s final attempt to convince the Ferrybank to refer him reminded me of a contestant on the X factor trying to convince the panel to give them a shot at stardom. I half expect them to ask him, “How much do you want it, Maxine? Do you really, really want it?”

“I’ve been too silent,” he muses. “… if I’d stopped trying to please everyone I could have been more true to myself. I’ve been living as Maxine for months now. I’ve stood up to bullies and people who don’t treat me as a girl. It feels right. In Boston there’s a trans-girl. She got her first puberty blockers injection: you should’ve seen the look on her face, it was peace. I want to feel that peace.”

Rather than Max’s simplistic view of the solve-all properties of puberty blockers setting off alarm bells, the panel seem convinced.

“My mum and dad aren’t at war anymore but my body and brain still are.” he concludes, and there isn’t a dry eye in the house as the family smile and hug and tell Max how proud they are.

Cut to the car park.

They all get into the car in silence- then burst into peals of happy laughter. The Ferrybank were convinced by Max’s eloquence! Everything is going to be perfect now!

Fast forward. Max is looking in the mirror.

“What sort of girl will I be?” he asks Vicky. “How real will I be? Will I be as real as you and Lily?”

“I think you already are.”

“Not undressed I’m not.”

“That will come. We’ve got a long way to go, but it will come.” says Vicky. “Look. You’re beautiful.”

Max looks in the mirror for a long time and then pouts.

Fast forward.

At the hospital, Max is receiving his first puberty blocking injection.

“Does it hurt?” asks Vicky.

“I’ll get used to it,” says Max and the music reaches a rousing crescendo as his parents hold hands and he smiles beatifically into the camera.

Credits roll.

What’s really interesting about the ending of Butterfly is that it’s not the ending. Max may well have been temporarily suspended in prepubescence but there is so much that is left untold.

No one seems to have trouble remembering to call him Maxine, everyone adjusts seamlessly. Max is now she, Maxine, a daughter, a girl… Max is indeed shut away in the dark under the bed.

Throughout the series,all those around Max have affirmed his feeling that he is actually a girl. His mother has kidnapped him and flown him halfway around the world so he can begin to be physically moulded into a girl. She has talked about him being ‘born in the wrong body’. She’s also made it clear, more than once, in his presence, that she doesn’t believe Max can survive without physical transition.

His dad, always disappointed in him as a boy, only shows true affection once Max presents as a girl. “Only girls hug you like this.”

What else struck me? Well, apart from the casual sexism, Max’s astonishingly unrealistic ability to perform a gauche version of femininity under all circumstances. Looking as if he’d just stepped out of a photoshoot after a ten hour flight from Boston and being seized from his parents, through medical procedures and early morning breakfasts, his blusher and eyeshadow remain perfectly in place, his lips are unsmudged, his hair perfectly coiffed.

Awkward as these trappings are, they are needed to convince the audience that Max is more than ‘just’ a feminine boy. Without the pretty hairgrips and the make up, how would we know?

When Max pouts into the mirror at the end, when Max talks about being treated like a girl, when he is given permission to hug his father and people finally start telling him he is beautiful, he is embracing the very trappings of femininity that patriarchy pushes on women whether they like it or not.

I feel as if I should have so much more to say with an analytical mind. To me the quotes seem to speak for themselves, showing the cognitive dissonance and the determination not to dig too deep, to fix what is on the surface without questioning what lies behind it. But I know that much of the general public doesn’t see it like I do, and that the series will continue to be described with words like truthful, powerful, heartfelt and sensitive.

It’s fiction, of course. It is what it is. Superficially it’s a happy ending, parents reunited, Max becoming what he’s ‘always been’. An advert for Mermaids, a cautionary tale, a dark science fiction piece worthy of the greats of the mid 20th century. It is what it is: a tale from a world where sexism masquerades as progressive; where the gender cult is heralded as liberating while it squeezes young people into boxes woven so finely they can’t even see the threads that hold them there.

All photos are screenshots from the ITV mini-series ‘Butterfly’

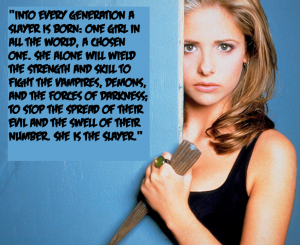

Buffy, of course, is a teenage vampire slayer, star of a cult TV series that bridged the 20th and 21st centuries. Episodes started with this opening ““Into every generation a slayer is born: one girl in all the world, a chosen one. She alone will wield the strength and skill to fight the vampires, demons, and the forces of darkness; to stop the spread of their evil and the swell of their number. She is the Slayer.”

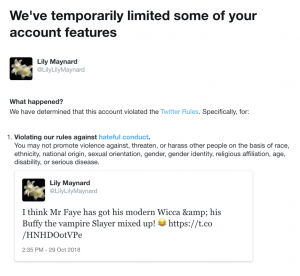

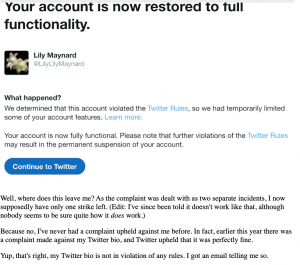

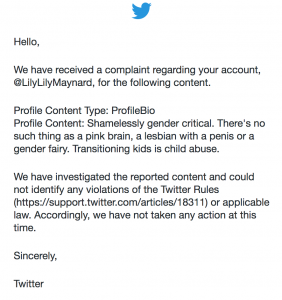

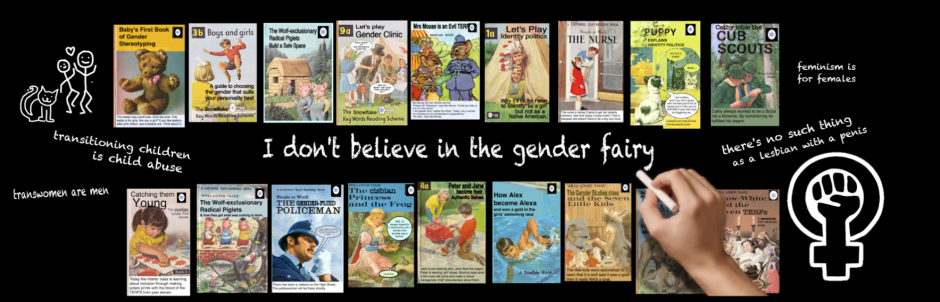

Buffy, of course, is a teenage vampire slayer, star of a cult TV series that bridged the 20th and 21st centuries. Episodes started with this opening ““Into every generation a slayer is born: one girl in all the world, a chosen one. She alone will wield the strength and skill to fight the vampires, demons, and the forces of darkness; to stop the spread of their evil and the swell of their number. She is the Slayer.” Well, I’ve never been in Twitter jail before. Better women than I have been forced out entirely, of course, Venice Allan and Posie Parker spring to mind, and numerous others are much missed, or have had to temper their speech in order to stay on a now watered-down platform.

Well, I’ve never been in Twitter jail before. Better women than I have been forced out entirely, of course, Venice Allan and Posie Parker spring to mind, and numerous others are much missed, or have had to temper their speech in order to stay on a now watered-down platform.

Although Vicky hasn’t made time to phone Stephen or Lily, Max has posted a selfie of himself and his mum on social media with the tag ‘Boston’.

Although Vicky hasn’t made time to phone Stephen or Lily, Max has posted a selfie of himself and his mum on social media with the tag ‘Boston’. “Turn into, transform, become, blah blah blah,” he waves his hand with a worrying lack of eloquence, or interest in the method of the wheels he’s about to set in motion.

“Turn into, transform, become, blah blah blah,” he waves his hand with a worrying lack of eloquence, or interest in the method of the wheels he’s about to set in motion.

Cut to Boston. Dr Lollypop tells Max he’ll see him in three months. Next stop the airport. As Max and Vicky arrive back in England, we see Stephen flexing his excellent parenting skills by turning up to watch Max being dragged away as Vicky is arrested under Section 1of the Child Abduction Act.

Cut to Boston. Dr Lollypop tells Max he’ll see him in three months. Next stop the airport. As Max and Vicky arrive back in England, we see Stephen flexing his excellent parenting skills by turning up to watch Max being dragged away as Vicky is arrested under Section 1of the Child Abduction Act.