The women of Twitter answer the billion dollar question.

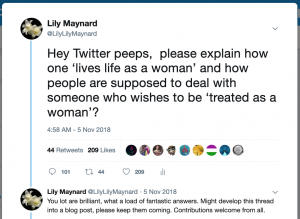

I asked “Hey Twitter peeps, please explain how one ‘lives life as a woman’ and how people are supposed to deal with someone who wishes to be ‘treated as a woman’?”

These are just some of the responses I received. A few have been shortened.

So. Now we know.

Woman: pay them less and ignore them in meetings? ?

Man: I’ve got a great idea: pay them less and ignore them in meetings… (Sorry, crap joke, *gets coat*)

Today a lot of male barristers interrupted me constantly in court. I sighed quietly and let them speak. Pretty sure that’s “living life as a woman.”

How does it actually ‘feel’ to be a woman? I am demonstrably one and I have no idea. Without resorting to superficial gender stereotypes, who can say how it ‘feels’ to be either sex.

It’s so sad that it’s assumed that all women ’feel’ the same. I don’t think there is enough recognition that we are all individual people with unique personalities, likes and dislikes as men are. We are not Stepford wives or mere sex objects. Is that clear enough?

“Lives life as a woman”? I think that means being paid less, judged on your appearance 24/7, interrupted constantly, and told you don’t know what you’re talking about by men who know far less.

Women just live. We deal with rape, assaults, periods, giving birth, guilt of being a working parent… Under pressure for our looks, makeup, weight etc in ways men aren’t but these are gender stereotypes. I’ve always been a woman. It’s not a feeling, it’s our anatomy. End.

I’m living life as a woman by dealing with a plumber who only wants to speak to my husband.

I’m living life as a woman by taking my husband to the household tip with me – apparently only men can put our rubbish into their correct container.

I’m living life as a woman by enduring office jokes about the menopause.

OMG I just asked this on another forum and haven’t had one direct answer yet, instead more accusations for asking the question, mainly by men. So today, that’s what living like a woman is, well that and dealing with a kid who won’t get in the shower while I’m making risotto.

Juggling, juggling, juggling – constant juggling of kids, work, meals, housework, while striving to include exercise, bit of a social life, all wrapped up in constant mild exhaustion and the banality of rarely being listened to or taken seriously. Yep that is it.

I’m living life as a woman by tidying my car (found a winning scratch card) and taking the cats to the vet. (I’m also growing a human being but that’ll happen no matter what I do at the moment)

This evening I am living as a woman by reading a sci-fi/spy thriller/lovecraftian horror book* while my husband cleans the kitchen and cooks dinner.

I live life as a woman by being invisible now I’m over 40.

I’m ‘living life as a woman’ by primping in my boudoir (pink of course).Oh wait, that’s never happened. I’m in jeans and working on a PowerPoint pres for tomorrow. Did manage to put on mascara though so I might squeak in at 2/10 in competitive wommaning 2018.

“Could you be a doll and take the coffee order? You’re so good at that!”

By doing men’s share of the emotional and relational work in our marriage, so that he can avoid being vulnerable and escape true intimacy.

I’m living as a woman by hiding from my kids in the bathroom, with my phone. I can hear them looking for me, I’m being really quiet (they are very annoying today!)

Sadly I have been womaning very badly today by working on engineering documentation all day and asking engineers pointed questions about their data. Also listening politely, nodding and smiling as appropriate. However I AM wearing a dress, so go me.

Well I would suggest just asking people to pay you less than men and to ignore your expertise or opinions. That’s a start.

I live life as a woman by presenting evidence for whatever I say, as being believed/respected is only automatic for men.

And apologising for having an opinion, even before I even express said opinion. I’m sorry. Just my opinion, of course.

As someone with a vagina who has been heavily socialised as a female from birth, I’m not sure I’m qualified to answer the question

Today, I ‘lived like a woman’ by having it gently explained to me on the internet (with much use of my username eg ‘actually, squirrel’ urgh) that if I insist womanhood is based on a biological ‘technicality’ then I am erasing women. Wokebro logic makes my dainty little head spin.

Spend a certain amount of time in intense pain and have doctors hint that you are imagining it.

Ignore that person’s right to bodily autonomy, never miss an opportunity to tell them how they are doing/saying/thinking something wrong, shamelessly steal credit for their ideas (inc those that you have previously derided), privilege their sexual marketability over everything.

I’m “living life as a woman” by listening to my husband complain about my daughter + vice versa. I’ll leave work shortly to give a statement to the police about a narcissistic psychopath whose rage might see him end up in court. Then it’s home to walk dogs and pick up shit.

As a Canadian, I’ve no idea. But if one were to immigrate to Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, etc., they can get the “full” woman treatment of clothing laws, having to be chaperoned by male relatives, being examined to verify virginity, honour killings, forced marriage, etc.

If the person who gave you stress incontinence gets your attention by pulling your bra down and screeching “mummah, NURSE!” you may be getting close…

As I can’t live my life as an otter, a man, a blackbird etc., I can’t answer this question.

Realise it’s Monday and that you haven’t had a shower since Friday. Realise you have to go out and pick up any random item of clothing off the floor and hope it’s clean. Pick your toenails. Spend most of time watching cat videos.

Think about other people’s needs all the time. Don’t expect to be taken seriously by men. Hide your considerable talents for fear of showing men up. Never quite feel entitled to anything much.

I live life as a woman by fixing bikes in a job that I can’t really afford to stay in but do because I can dictate the hours I can do around my childcare situation. So, part-time, low-paid, despite my degree. I do like being oily and wearing trousers though. Must be a fake woman.

Being the one person in the house who knows where anything is? (Apart from the toolbox, obviously).

A couple of weeks ago I was womaning in the hospital for 3 days with a massive abscess between my ovary and fallopian tube.

Today I lived as a woman by not sleeping all night and getting up to discover my barely there period has decided to stay for 2 weeks. Laundry time….

I’m living my life as a woman by being a middle-aged freelancer and earning exactly a tenth of what I earned ten years ago for the same work.

Try being a white haired woman over 60 who lives on her own, doesn’t wear make up and only wears flat shoes. Invisible woman is how I get treated!

A woman fosters life, nourishes growth in herself and others, and knows her dignity. Her femininity shapes society. When these values are withered down or pushed aside, women find themselves used, with low self esteem, and desperately trying to imitate men. Embrace womanhood.

For me, one lives life as a woman constantly wondering why people are arguing with me over common sense things (because, as I don’t walk around feeling ‘less than’, it never occurs to me that there is a reason my opinion is not being taken seriously).

You must wait patiently whilst middle age men laugh uproariously after you mention that you are buying a FIAT 500. They will talk about having to push it up hills, and snigger when they ask what colour you chose. Remember, this is hilarious.

This is a question which genuinely confuses me. I am a woman, I am autistic so struggle a LOT with things being redefined or commandeered. What makes me feel like a woman? I have no idea. How do I live my life as a woman? I just do. Because I am one.

Well first off they should do ALL the washing up.

I, for one, can’t live ‘as a wo +man’. I’m not a man. Fem was renamed (wo) man in 11th C to support patriarchy, and this is exactly what it does.

I’m really tempted to say pay them less than men and sexually abuse them but I don’t suppose that’s the right answer. It reflects reality though.

I don’t know the first one even though I am a woman. I just do me. The second? The same as I treat everyone else to be fair x

I’m living life as a woman while dealing with dysmenorrhea and ovulation pain EVERY SINGLE MONTH intercalated every 13 days. And having men saying “that’s why women should be submissive, their weak”… my ass!

Getting ready for a job interview and trying not to look too much of anything….a bit of makeup to look professional but not too much…heels but not too high – slutty and frivolous …smart tailoring but can’t make my butt look too good etc

Getting tail gated when following the speed limit and shouted at by male drivers.

Asking the gyno NP about my tanking libido with perimenopause, and getting “It happens. Not much we can do about it ¯\_(ツ)_/¯”

I live life as a woman by suffering from ME, the hysteria of our times, and being treated as though it were a psychological condition because it’s a ‘women’s illness’.

The only thing that makes you a woman is being born female. There is no set of social conventions or set of behaviours specific to women.

Guys, I’m not sure I’m womaning correctly. Today I complained to the electrician who cut a hole in my ceiling & left it there. I insisted he return to patch the hole, & he condescended to me & said I must not know how to use a power drill. I snapped at him. Am I still a woman?

I treat people as people but I always risk assess biological/natal males- every single time.

No idea. It’s my life, l live it. I hope I’m respectful to others, expect no less in return. Doesn’t always work out. Keep on trying.

Give them the household organising: packed lunches, permission form for school trip. Kids need dentist. Send birthday card to Auntie. Rubbish out tomorrow, oh God have we paid electric bill? RSVP party invite. Clean uniform. What’s for dinner? Done homework? Shopping order.

For me, living life as a woman means being on constant alert while in public places and jumping out of my skin when men raise their voice.

I live as a woman by automatically being 90% responsible for the childcare responsibilities for our child. 100% for my first child. I’m treated as a woman because it’s not considered “real work.” And I’m always last in the queue for the bath or a break.

Today I lived life as a woman by watching the salesman in the computer store direct all attention at my husband until I explained why – I – need the i9 processor in the laptops for – MY – business. Lol.

My authentic female experience of the day involved me running the toilet as soon as I got to work due to a close encounter of the menstrual kind and finding out that I’d leaked all over my underwear.

I’m living my life as a woman by sharing my morning ablutions (& tweeting on the loo – bit crowded in here, zero privacy) w/ 3 kids under 5 before getting them ready for pre-school, & spending the day studying tax law while surreptitiously eating said children’s Halloween treats.

If someone wants to be treated like a woman try walking home from pub alone and being so scared you hold your keys as a weapon. Also try being ignored in meetings and being told to smile more to make you prettier.

Spent all day fixing stopcocks, soldering, making up diluted acid from concentrate, maintaining 6 fish tanks, in jeans and trainers. Paid less than living wage for hours that fit round my kids – that should give you a clue to my sex!

Unless you’re living with the things that females have to live with because of their biology, you can’t. You’re either female or you’re not. If you aren’t a female all you can ever do is copy what you perceive a female does. That’s acting.

Easy peasy: 1. Don’t listen to them 2. Do everything possible to silence them 3. Demand they do more than you 3. Tell them to STFU when they try to raise valuable issues 4. Hit them and blame them.

To treat someone as a woman, do the following: Talk over her, explain things she already knows (slowly and using simple words) and offer unsolicited advice.

Don’t ask me, womaning is a mystery to me. Yet somehow, I am still a woman, amazing.

I’ve lived my life as a woman today by being annoyed that I can’t even walk down the fucking street in a straight line without stress because men expect you to move out of the way for them (spoiler alert, men: I don’t).

I’m living as a woman by never being the parent who takes kids to doctors when they’re sick. Husband is treated with respect and understanding by GP when he goes, I’m treated as if I’m suffering from munchausen by proxy.

Accept being mansplained at even by your nearest and dearest without objection least you be seen as rude. (Husband explained probability to me the other day, I have a BSc Mathematics, he hasn’t done maths since finishing high school)

Get them to make the refreshments for everyone at board meetings – even if they happen to be the Head of Mergers and Acquisitions. Even better, make the request while they’re in the middle of giving a presentation, then fight over the sugar and sandwiches while they’re talking.

Sandwich them between children & ageing parents. Get them to feed & clothe all of the above whilst doing a full time job. When they finally collapse into bed of a night soak them regularly in hot water. If duvet still usable, more water!!!

Treat their medical complaints as largely psychological, and then when they get frustrated that they’re not being heard, use that frustration to confirm that they’re just being overly emotional, and attention seeking.

I think it means live as a human in possession of a female body.

I’m living as a women by wearing pink pyjamas and because I have lady pink brain.

Ignore them. Pay them less but demand they do more work. Expect they do all emotional labor. Let them do all the domestic work. Judge them on looks & find them wanting. Stop them & make them listen endlessly to your day. Use them for selfish sex. Tell em to smile you know, like women.

Ignore them when they speak; talk over them. Treat them as if they are less intelligent than you. Expect them to meekly acquiesce to men… The list goes on…

Do a favour for a friend and open storage locker for removal company. One guy turns up. Spend 2.5 hours hefting furniture, increasingly uncomfortable in confined space. Give tip. Get hit on despite loudly and repeatedly mentioning husband + kids and being forty fucking seven.

One is curfewed, one is permanently alert, one is permanently self conscious, one is always conciliatory, one is dismissed, one smiles, one does the ‘wifework’, one is object of the gaze, one is object, one cannot object….

Well for starters that would mean paying her less for the same job mansplaining basic shit, telling her to “cheer up, it may never happen”, staring at her breasts or legs, gaslighting her and violently threatening her on social media if she has different opinions to yours. Obvs.

To deal with someone who wishes to be treated as a woman? Hand them a loo brush and suggest they crack on. There’s a load of washing to be done and the kids want their tea.

Clean a lot of toilets, take a pay cut, do the majority of child and elderly care. Experience a lot of random harassment or actual violence. Listen intently as men explain stuff, including your ideas. Oh. And disappear from public view when you turn 50.

If they want to be ‘treated like a woman’, they should expect to be commodified, discriminated against, objectified, not taken seriously, joked about, humiliated & demeaned regularly and at risk of rape & domestic violence.

I’m living my life as a woman by searching for my partner’s car keys …. again.

For those that wish to be ‘treated as a woman’ just ignore them, nobody gives a fuck what women want.

I haven’t the foggiest clue. Apparently I’ve been doing it all utterly and tragically wrong for decades.

Go to view a property with a male friend, and watch the estate agent conduct all financial discussion with the person who hasn’t got half a mil in their pocket, and then turn to you smiling, saying, ‘look, room for a dishwasher’.

Grand rounds, am clinic, pm lab, go home to a nice meal my husband made, and order tampons online.

My life as a woman currently is living with an auto immune disease ( conservative estimates suggest 78% of the people affected with autoimmune diseases are women) and feeling guilty for not fully embracing my role as mother/grandmother dues to illness.

Cut their salary and start harassing them from white vans. #lifeasawoman

“Living as a woman” would mean being porn-dressed up all the time and sashaying around (certainly no chores or childcare). To treat them properly, one should cat-call them, objectify them very overtly; praise them on their womanliness.

I’m living my life as a woman walking into town only to find the shop I need isn’t open on Mondays and then walking back to clear up dog shit in the back garden. Wearing trousers and bugger all make up. Woman enough?

Most of us wear jeans and trainers or boots this time of year – in case someone wants to know what they should be wearing. T shirt and maybe a jumper or cardi. The stretch jeans are the comfiest.

Yup. It’s about all I own, along with the same T-shirt in about 10 different colours and the same for hoodies. Boots and trainers.

That is something I have wondered. I live my life as me. I don’t wake up thinking ‘I shall live like a woman today’. It is daft.

Do everything a man tells you to do, and don’t forget to smile.

I can’t say I was a gender nonconforming child. I hated wearing dresses to school, but that was only because I wanted to goof around, and frilly dresses got in the way. I did love one long, plum colored dress of mine because it made me feel like a mysterious princess. I loved my Barbies (though I also loved to rip their heads off), and I loved the Barbie movies. I browsed wedding sites, daydreaming about which one would be mine someday. I loved Hannah Montana (but maybe in a gay way now that I think about it) and Camp Rock. I was overjoyed if I got a kids makeup kit for Christmas – I loved all the different colors that I now recognize were all just tinted chapstick. I was pretty gender conforming, but then again, I tried to conform to everything.

I can’t say I was a gender nonconforming child. I hated wearing dresses to school, but that was only because I wanted to goof around, and frilly dresses got in the way. I did love one long, plum colored dress of mine because it made me feel like a mysterious princess. I loved my Barbies (though I also loved to rip their heads off), and I loved the Barbie movies. I browsed wedding sites, daydreaming about which one would be mine someday. I loved Hannah Montana (but maybe in a gay way now that I think about it) and Camp Rock. I was overjoyed if I got a kids makeup kit for Christmas – I loved all the different colors that I now recognize were all just tinted chapstick. I was pretty gender conforming, but then again, I tried to conform to everything. My friends began to dwindle away. I stopped organizing skating nights. I started eating lunch alone. I got a lot of acne. I went from just another weird kid like everyone else to THE weird kid. I began to notice my weight. I began to really notice my weight. I didn’t look like the girls I saw with boyfriends. I didn’t bring a fruit salad to lunch. I felt like an intruder walking into a Hollister, or even a mall in general. I wasn’t supposed to be there, I wasn’t like other girls. I wish I knew the other girls felt this way too.

My friends began to dwindle away. I stopped organizing skating nights. I started eating lunch alone. I got a lot of acne. I went from just another weird kid like everyone else to THE weird kid. I began to notice my weight. I began to really notice my weight. I didn’t look like the girls I saw with boyfriends. I didn’t bring a fruit salad to lunch. I felt like an intruder walking into a Hollister, or even a mall in general. I wasn’t supposed to be there, I wasn’t like other girls. I wish I knew the other girls felt this way too. I watched Skylar Kergil and other trans people on Youtube. Skylar said he knew he was a boy when he had a crush on a girl and felt gross imagining being with her as two girls. I knew trans boys always hated wearing dresses, and would scream until they were off. I felt all of that. The thing was, these kids had always known… so I couldn’t possibly be trans, right? But I’m an intelligent person. I overanalyzed every thought and action and word in my life until I made it make sense. As always, I bent my own psyche into submission in order to conform. And so I conformed – in the most beautifully sinister way that convinces you that you’re doing anything but conforming – you are special, radical, and oh so valid.

I watched Skylar Kergil and other trans people on Youtube. Skylar said he knew he was a boy when he had a crush on a girl and felt gross imagining being with her as two girls. I knew trans boys always hated wearing dresses, and would scream until they were off. I felt all of that. The thing was, these kids had always known… so I couldn’t possibly be trans, right? But I’m an intelligent person. I overanalyzed every thought and action and word in my life until I made it make sense. As always, I bent my own psyche into submission in order to conform. And so I conformed – in the most beautifully sinister way that convinces you that you’re doing anything but conforming – you are special, radical, and oh so valid. If I could never become one of the black and white faceless thigh gaps, then maybe I could become the beaming boy with the swooping hair who says his muscles really started showing up after T. He used to be a girl like me. I was meant to be a boy. I have always been a boy.

If I could never become one of the black and white faceless thigh gaps, then maybe I could become the beaming boy with the swooping hair who says his muscles really started showing up after T. He used to be a girl like me. I was meant to be a boy. I have always been a boy. And so it went on for three years, until just weeks after my 18th birthday, I managed to get testosterone in August of 2016. One appointment, one hour, one vial of intramuscular injections that would change my life forever.

And so it went on for three years, until just weeks after my 18th birthday, I managed to get testosterone in August of 2016. One appointment, one hour, one vial of intramuscular injections that would change my life forever.