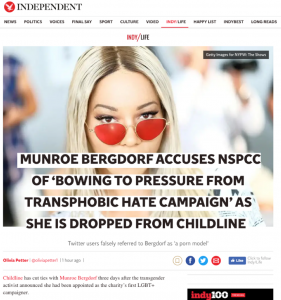

On 5th June 2019 the NSPCC announced their new ChildLine ‘influencer’ for ‘LGBT+ youth’: Munroe Bergdorf, a 30 year old male who began ‘transitioning from male to female’ age 24.

Selected as L’Oreal’s ‘first transgender model’ in 2017, Bergdorf was dropped as quickly as they picked him up after he made controversial public statements about how all white people were racist and had built their ‘existence, privilege and success’ on ‘the backs, blood and death of people of colour’. Personally, I thought some of what he said was fairly accurate on that occasion, but perhaps those who claim to promote love, tolerance, acceptance & diversity should be a little more careful what they say and where.

In February 2018, he was appointed as an LGBT adviser to the Labour Party, resigning less than two months later.

Later that month, Bergdorf angered women by writing an article for Grazia magazine where, in an ultimate act of mansplaining, he accused women of doing feminism ‘wrong’ and complaining that women did not see him as a real woman. ‘A woman is more than a vagina,” he complained, going on to call pink pussy hats ‘a well-intentioned yet misguided symbol of women’s equality’.

Later that month, Bergdorf angered women by writing an article for Grazia magazine where, in an ultimate act of mansplaining, he accused women of doing feminism ‘wrong’ and complaining that women did not see him as a real woman. ‘A woman is more than a vagina,” he complained, going on to call pink pussy hats ‘a well-intentioned yet misguided symbol of women’s equality’.

On Twitter he claimed that ‘centering reproductive systems’ at the heart of women’s marches was ‘reductive and exclusionary.’

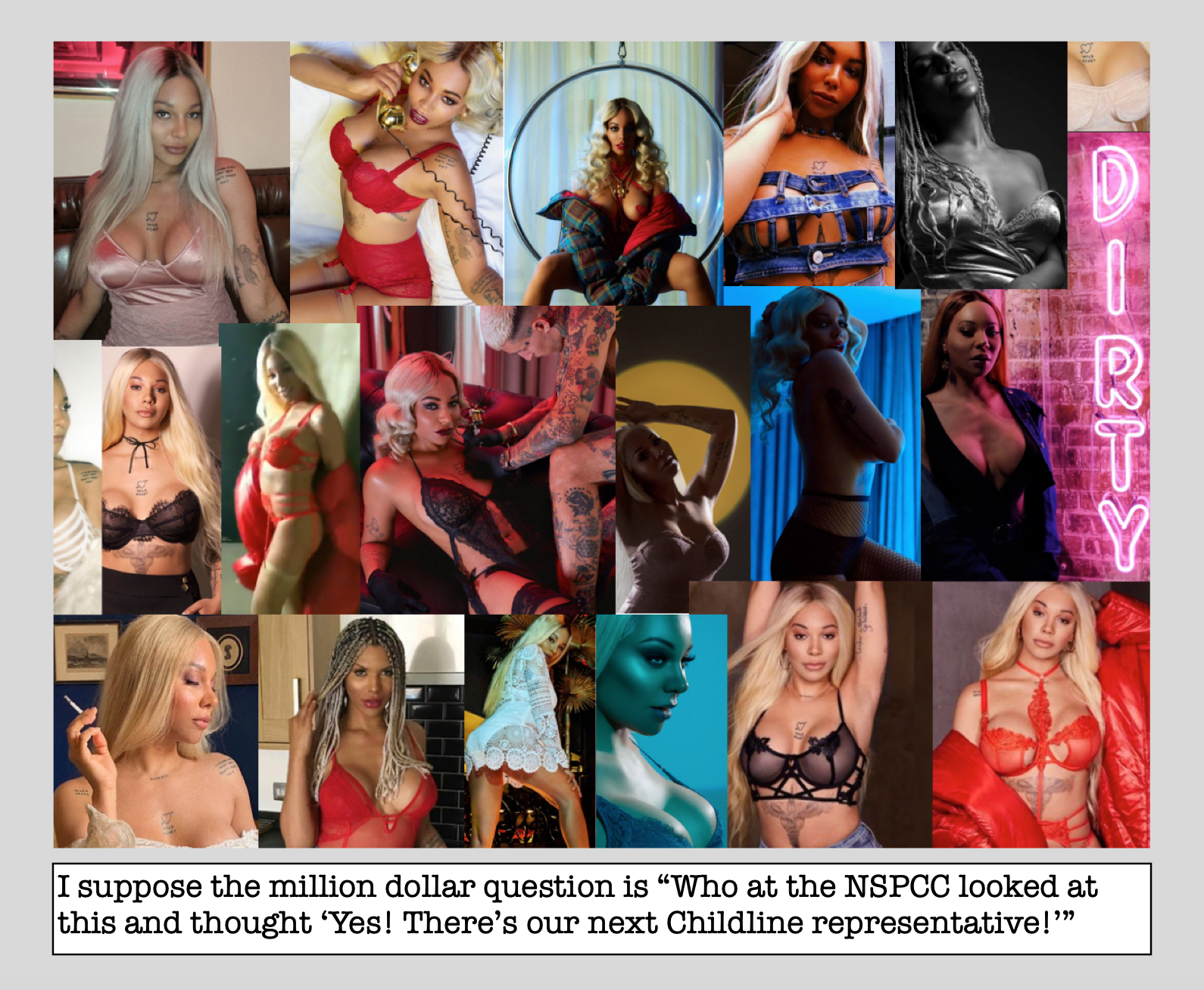

In May 2018 Bergdorf said he was ‘honoured’ to appear in a photoshoot for soft-porn magazine Playboy.

In May 2018 Bergdorf said he was ‘honoured’ to appear in a photoshoot for soft-porn magazine Playboy.

More controversy was fuelled when in June 2018 the British Film Institute (BFI) appointed Bergdorf- who has no experience as a film maker (or as a woman)- to be the keynote speaker of its ‘Women with a Movie Camera‘ summit. An open letter of complaint from women who questioned the suitability of a male for the role called the selection:

“an an insult to all the women film-makers who struggle on a daily basis to get their films made,” asking, “What kind of cultural work is being performed when a male is speaking on behalf of women film-makers?”

The BFI did not step down – and Bergdorf did not turn up.

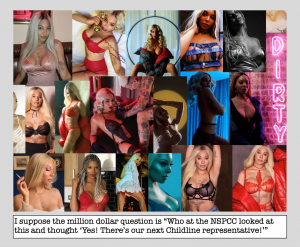

Bergdorf is now an underwear model who spends much of his time posing for semi-pornographic photoshoots, as you can see in the montage above.

So how did we get to the place where a man whose main interest seems to be showing off his now-substantial bosom to a camera lens gets to be an ‘influencer’, an ambassador for vulnerable children? Well, first we should look at a bit of the background to both the NSPCC and Childline.

NSPCC

The NSPCC was formed in 1889, in a time when animals had more rights than children, having campaigned to get the first ever UK law to protect children from abuse and neglect. The NSPCC is the only UK charity granted statutory powers under the Children Act 1989, allowing it to apply for care and supervision orders for children at risk.

The NSPCC was formed in 1889, in a time when animals had more rights than children, having campaigned to get the first ever UK law to protect children from abuse and neglect. The NSPCC is the only UK charity granted statutory powers under the Children Act 1989, allowing it to apply for care and supervision orders for children at risk.

The NSPCC’s core values are based on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- Children must be protected from all forms of violence and exploitation

- Everyone has a responsibility to support the care and protection of children

- We listen to children and young people, respect their views and respond to them directly

- Children should be encouraged and enabled to fulfill their potential

- We challenge inequalities for children and young people

- Every child must have someone to turn to

Worthy aims indeed. Undoubtedly the NSPCC has done some incredible work although in recent years it has been no stranger to controversy.

In the 1990s NSPCC provided a publication known as Satanic Indicators to social services around the country. These guidelines led to some social workers making false accusation of child sex abuse and a scandal ensued, involving accusations that the NSPCC had kept quiet in order to protect its income.

In 2002, in the wake of the Victoria Climbé case, former barrister Lee Moore said the NSPCC “seem reluctant to get involved (in child protection cases) as it might hurt their marketing campaigns… what is its priority: children or fundraising?”

In 2007 Patrick Butler wrote in the Guardian that NSPCC campaigning is “flawed and naïve” and that there is “zero evidence” that £250m the NSPCC spent on their “Full Stop” campaign between 1998-2007 actually benefited any children.

In 2014 the NSPCC claimed home education was a ‘key factor’ in child abuse cases, a position from which they were forced to backtrack after it was revealed that the children cited were all known to the authorities. 2014 FOI requests showed that home educated children are actually at lower risk than other children.

In March 2018 it was revealed that the NSPCC’s funding had fallen by nine million pounds. The more cynical among us might suspect that this is their reasoning behind jumping on the trans-train, a cash cow if ever there was one. Nine million sounds like a lot but is really just a rather large drop in the ocean: in 2017/18 the NSPCC’s total income was a whopping £118.3m and Peter Wanless, the charity’s chief executive was paid between £170,001 and £180,000.

Childline

Childline was started in 1986 by Esther Rantzen in response to a television program about child abuse. The idea of a phoneline where children could ring to report abuse or for someone to talk to was revolutionary and without doubt it has changed lives for the better.

Childline was started in 1986 by Esther Rantzen in response to a television program about child abuse. The idea of a phoneline where children could ring to report abuse or for someone to talk to was revolutionary and without doubt it has changed lives for the better.

In 2006 Rantzen said “There’s so much pain in life that you can’t avoid, but I don’t think there’s any cause more crucial than protecting children from the avoidable pain.”

The NSPCC absorbed ChildLine in 2006. By 2011 the service had been called by over 2.5 million children, had 12 call centres in Britain and was the model for similar services in 150 countries.

ChildLine celebrated it’s 30th birthday in 2016 and has achieved some incredible successes, estimating that it has helped over 4.5 million children in those 30 years. A Minister for Children was appointed to the UK government as a direct result of ChildLine campaigns.

However, ChildLine seems to have developed a new trajectory in the last year.

A ChildLine report dated 5th June 2019 reveals that last year they carried out 6,014 counselling sessions with children and young people ‘about issues relating to gender and sexuality’. They received an average of 16 calls a day from children with concerns about ‘coming out’, a 40 percent increase on last year. ChildLine in Leeds counselled more than 250 youngsters on gender and sexuality issues last year.

How many of those sessions were concerned with gender identity, I wonder? We can perhaps get some idea of this from the fact that there has been an 80% increase in the number of views of its gender identity webpage in the last year.

The Childline report cited above refers the case of a boy (sic) who reported: “I’ve been feeling depressed and suicidal for about 3 years. My parents don’t understand me at all. I came out as trans and they think it’s just a phase and refuse to accept me.”

A visit to Childline’s homepage highlights four areas where children might wish to express concerns. The first of these is ‘gender identity’.

In 2006, ChildLine received three times as many calls from girls than boys. In 2019, type in ‘trans’ on the ChildLine homepage and seven out of the ten hits are from girls who want to be boys.

“My boyfriend are both trangender (assianged (sic) female at birth)… on social media I follow this person, and he was a girl but then he came out and is now transgender. He is a boy now, and I think I wanna be like that!… I’m trans ftm and am out to everyone and my school is really supportive but I don’t really feel much better… i have always felt like a boy, being born a girl, and 50% of the time, i feel like a boy, but the other half i feel like a girl, altough (sic) not a very feminine one at all… I came out to my mom through a letter that I’m trans a few months ago…(she) still thinks me liking girls is a phase... I don’t feel like a girl and I want to tell my parents how I feel, but I don’t feel like I’m allowed to identify as transgender because I love certain feminine things, like dresses and shoes…

‘Sam’ offers careful, mostly generic advice to these young people. ‘Sam’ never suggests a child might not be trans, at one point commenting mysteriously, ‘if people only think of gender in ‘normal’ ways, stereotyping can start to happen. There is no such thing as normal.‘ Sam doesn’t explain how we are supposed to think of gender. When a girl who ‘came out three years ago as a lesbian’ but now believes she is a boy writes to Sam she is advised to contact ‘Gendered Intelligence’.

Gendered Intelligence

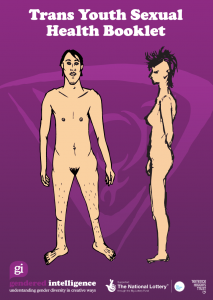

In case you haven’t come across it before, Gendered Intelligence’s advice for teens in their Trans Youth Sexual Health Booklet includes this gem: ‘a woman is still a woman even if she likes getting blow jobs. A man is still a man even if he likes getting penetrated vaginally’. So that clears that up then.

In case you haven’t come across it before, Gendered Intelligence’s advice for teens in their Trans Youth Sexual Health Booklet includes this gem: ‘a woman is still a woman even if she likes getting blow jobs. A man is still a man even if he likes getting penetrated vaginally’. So that clears that up then.

In the opening section of GI’s NHS endorsed ‘Guide for Young trans-People in the UK‘ one young trans person expresses ‘a feeling of alienation from my prescribed gender role‘. Another is quoted as saying they didn’t usually use the label trans but were told ‘by an acquaintance at NUSLGBT conference in Summer 2005 that I counted as a valid trans person.’ So even if you don’t think you’re trans, you might be.

The booklet goes on to warn trans-identifed youngsters that their parents may react with ‘outbursts of rage from shock‘ when they reveal they are trans. It advises trans-identified boys to ‘perfect the bum swish‘ as they walk and recommends a website where trans-identified girls can get a ‘reliable binder… to create a more male-appearing chest’.

These resources are recommended to children by ‘Sam’ on the ChildLine website.

Stonewall Youth

The NSPCC directs children to Stonewall Youth‘s LGBTQ info which erroneously tells confused kids that everyone has a gender identity.

“Your gender identity is a way to describe how you feel about your gender. You might identify your gender as a boy or a girl or something different. This is different from your sex, which is related to your physical body and biology. People are assigned a gender identity at birth based on their sex.”

In search of clarification as to how someone who ‘doesn’t feel that they are either a boy or a girl’ might feel? Stonewall Youth has the answer.

“They might feel a combination of the two or at times, one or the other.”

“if you identify as a girl you might want to dress in a certain way or read certain books” adds Stonewall Youth, helpfully, under a paragraph entitled ‘gender expression’.

Can we have a definition of ‘trans’ please, Stonewall Youth?

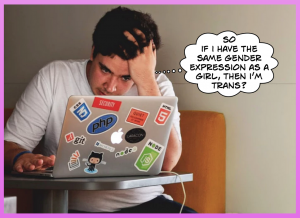

“someone whose gender identity or gender expression is different from the gender that they were assigned at birth.”

Hang on – your gender expression makes you trans? You mean, like, playing ballet or football? Having long hair or short hair? Oh, of course, that was the bit about wanting to dress a certain way or read certain books.. wait.. if I’m a boy and I read ‘girls’ books’ I’m trans?

Hang on – your gender expression makes you trans? You mean, like, playing ballet or football? Having long hair or short hair? Oh, of course, that was the bit about wanting to dress a certain way or read certain books.. wait.. if I’m a boy and I read ‘girls’ books’ I’m trans?

Is this really helping children feel comfortable with themselves?

Protecting gay kids

I type ‘gay’ into the Childline home page and the first hit is ‘sexuality’ and a link that starts off by telling you what LGBTQ+ means. Although I’m assured that ‘gender identity isn’t the same as sexuality’ there is a convenient link to the gender identity page long before anything concerned with same sex attraction. In fact I saw the term mentioned only once (see below). Instead, curious children are told that they might want to ‘try to find a sexuality that fits how you feel‘ and that ‘it’s okay not to be sure’. Confused? You will be.

“You can’t ‘find a sexuality that fits’. You just do you.” scoffs middle child, who has come in search of a cooked lunch to find her mother still in her pyjamas, tapping away on her laptop in the middle of an unmade bed. “Will you make me some veggie sausages?”

After lunch I return to the ChildLine website and the section called ‘Sexuality Definitions’.

Sexuality

The veggie sausages have filled me with renewed hope.

I am disappointed to be confronted with this:

Homoflexible? Heteroflexible? What the very fuck are they going on about?

A child wondering about being attracted to both girls and boys would come across this gem: ‘Bicurious – people who don’t see themselves as either heterosexual or homosexual, but may also sometimes be curious about the gender they’re not normally attracted to.‘

If you don’t want to leap into bed with every Thomasina, Dick and Harriet you come across, there’s a definition just for you too. Sort of.

Demisexual: Someone who doesn’t have any sexual attraction unless they have a strong emotional connection with someone first.

Here’s another.

Crossed orientation (or mixed orientation): People who experience a romantic or emotional attraction that is different from their sexual attraction. For example, someone may feel emotionally attracted to girls but sexually attracted to boys.

Polysexual: Someone who is emotionally and physically attracted to some genders, but not all.

Some genders but not all?

SOME GENDERS BUT NOT ALL?

I am put in mind of Angelicat.

Angelicat is a meme created by a woman after she read about ‘angeligender’ on Tumblr “A gender found only among angels that is hard to describe to non-angels. For godkin and angelkin only.”

Angelicat is a meme created by a woman after she read about ‘angeligender’ on Tumblr “A gender found only among angels that is hard to describe to non-angels. For godkin and angelkin only.”

As I scroll through the ‘sexuality rainbow’ (which makes me want a piece of rainbow cake with my third cup of coffee whilst also making me feel slightly sick) I do find a brief moment of clarity on seeing that ‘gay/homosexual’ is defined as ‘feeling emotionally and physically attracted to people of the same sex‘.

However, ChildLine is not so clear with its definition of the word lesbian. Lesbians are ‘girls who are emotionally and physically attracted to other girls’.

This, coming from an organisation that believes that boys can actually be girls if they identify as such, raises serious concerns about protecting the definition of same-sex attracted females.

If the definition of ‘girl’ includes a boy who thinks he’s a girl, where does that leave young lesbians? Do ChildLine’s protections not stretch to advocating for the right of girls to say they’re only attracted to other female-bodied people?

While the ‘sexuality definition rainbow’ is the sort of obsessive self-evaluation that we might expect to find on the Instagram page of your average navel-gazing teen, or clasped between the glittery paws of Angelicat on Tumblr, let’s be serious for a moment.

Let’s step back and remind ourselves that Childline is directly linked to the NSPCC. It is they who are feeding this nonsense to vulnerable children, presented as fact.

What’s next?

‘Childline’s first LGBT campaigner’

Just when you think things can’t get any more absurd, the NSPCC appoints Munroe Bergdorf as a Childline representative for LGBT youth.

Just when you think things can’t get any more absurd, the NSPCC appoints Munroe Bergdorf as a Childline representative for LGBT youth.

Bergdorf tweets that he is ‘proud to be announced as @childline’s first LGBT+ campaigner’.

“The wellbeing and empowerment of LGBTQIA+ identifying children and young people is something that I have been passionate about throughout my career as an activist.”

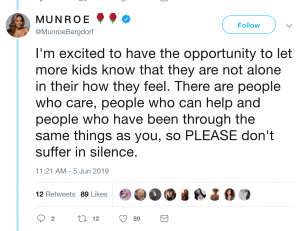

“I’m excited to have the opportunity to let more kids know that they are not alone in their how they feel. There are people who care, people who can help and people who have been through the same things as you, so PLEASE don’t suffer in silence.”

“I’m excited to have the opportunity to let more kids know that they are not alone in their how they feel. There are people who care, people who can help and people who have been through the same things as you, so PLEASE don’t suffer in silence.”

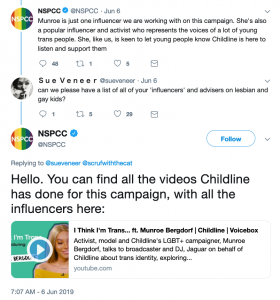

“Munroe is just one influencer we are working with on this campaign.” tweets the NSPCC, enthusiastically. “She’s also a popular influencer and activist who represents the voices of a lot of young trans people. She, like us, is keen to let young people know Childline is here to listen and support them.”

ChildLine has produced a series of videos and Bergdorf stars in one. ChildLine posted proudly on Twitter about the partnership using Munroe’s video as the thumbnail to promote the campaign.

It seemed as if the alliance was in full force.

So what do we know about Bergdorf?

Unhappy as a boy, taunted for being gay, Bergdorf’s solution was to undergo huge breast implants and extensive face feminisation surgery in order to better ‘pass’ as a woman. It cannot have been easy for him and he seems happy with the result. Indeed, the transformation has been extensive.

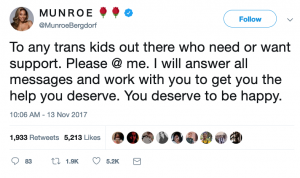

In November 2017 Munroe sparked controversy and showed a blatant disregard for child safety protocols by tweeting that trans-identified children should contact him directly by private message. Several young people tagged him and were told ‘DM me‘. The next day he posted again telling kids to contact him via Instagram, concluding ‘you gotta big sister here, always’.

In November 2017 Munroe sparked controversy and showed a blatant disregard for child safety protocols by tweeting that trans-identified children should contact him directly by private message. Several young people tagged him and were told ‘DM me‘. The next day he posted again telling kids to contact him via Instagram, concluding ‘you gotta big sister here, always’.

The plastic surgery alone should raise a red flag for those selecting a figurehead – surely we want children to learn to be happy in their bodies? Bergdorf’s transition is well documented online. He says one of his reasons for surgery was how he felt looking at himself in the mirror without make up; that there was a point when he felt unable to leave the house. In addition to the breast implants he underwent extensive ‘facial feminisation’. ‘I got my chin re-contoured and moved forward, my brow bone re-contoured, a brow lift, and liposuction under my chin.’

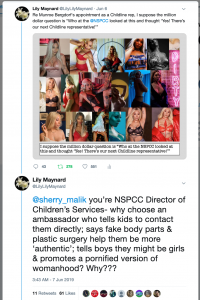

Re his appointment as a ChildLine rep, I suppose the million dollar question is “Who at the NSPCC looked at this CV and thought ‘Yes! There’s our next ChildLine representative!’”

One thing we can be pretty sure of is that no woman who made a living posing in a lacy bra next to a neon sign reading ‘Dirty’ would ever be chosen to represent a children’s charity.

*Edit: I’ve since been informed that both Abbey Clancy & Melinda Messenger have been ambassadors/influencers for Childline. I’m surprised.

This is not about prudery, it’s about appropriate behaviour for an ambassador for children. Kids that call ChildLine are often already incredibly vulnerable. Introducing them to the idea that soft porn, fake body parts and plastic surgery can help them be more ‘authentic’ is just a horrendous concept.

I tweeted at the NSPCC Director of Children’s Services but received no reply.

I tweeted at the NSPCC Director of Children’s Services but received no reply.

Others tweeted at Chief Executive Peter Wanless and received no reply.

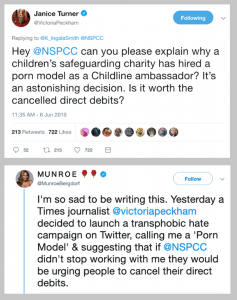

I noticed that journalist Janice Turner had tweeted at the NSPCC. She also received no reply. Bergdorf responded by describing Turner’s concerns as a ‘transphobic hate campaign’and Turner’s suggestion that the NSPCC might lose revenue from the decision as ‘urging people to cancel their direct debits’.

Bergdorf denies being a porn model, despite his appearance in Playboy and various similar publications.

On the left is the Merrriam-Webster dictionary definition of pornography. For examples of Bergdorf’s photoshoots, see again the header picture for this article.

On the left is the Merrriam-Webster dictionary definition of pornography. For examples of Bergdorf’s photoshoots, see again the header picture for this article.

What’s wrong with being a porn model? Well, that’s a political and theoretical discussion in itself, liberal feminism working on the principle that because a handful of women find it ’empowering’ we should overlook the thousands of others who are trakkicked drugged, raped and abused within the global sex industry; radical feminism looking at how it affects women as a class.

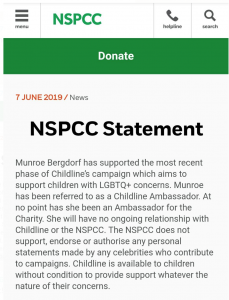

Around lunchtime today, the Independent released an article in which it claimed that Bergdorf had been ‘dropped from ChildLine’. Yet the NSPCC claim ‘At no point has she been an Ambassador for the Charity. She will have no ongoing relationship with Childline or the NSPCC.’

Bergdorf hit back:

“This Pride Month Childline had the opportunity to lead by example and stand up for the trans community, not bow down to anti-LGBT hate and overt transphobia.”

“But instead they decided to sever ties without speaking to me, delete all the content we made together and back-peddle without giving any reason why.”

Concerning this last objection, he has my sympathy. The NSPCC has behaved in a cowardly, duplicitous manner. Just as they refused to answer messages from those expressing concerns about Bergdorf’s role, so they appear to have unceremoniously dumped him when it suited them.

More importantly, in some ways, is the way they have kowtowed to gender ideology. Both with the inclusion on the Childline website of such nonsensical resources as those featured above, and the inclusion of links to dubious groups like Gendered intelligence and Stonewall Youth.

The NSPCC comes out of all this with egg on its face, once again.

It appears that not only is Broadgreen Primary School in Liverpool a Stonewall Champion, with nursery age kids learning about the joys of being non-binary, but the year 1 pupils – that’s five and six year olds – spent the morning of June 24th studying a book called ‘Jack (not Jackie)’.

It appears that not only is Broadgreen Primary School in Liverpool a Stonewall Champion, with nursery age kids learning about the joys of being non-binary, but the year 1 pupils – that’s five and six year olds – spent the morning of June 24th studying a book called ‘Jack (not Jackie)’.

This ‘sweet story of change and acceptance’ advocates for anything but acceptance. The message is very clear – a girl who doesn’t want ‘swingy’ hair and likes superhero capes and mud is quite probably a boy.

This ‘sweet story of change and acceptance’ advocates for anything but acceptance. The message is very clear – a girl who doesn’t want ‘swingy’ hair and likes superhero capes and mud is quite probably a boy.

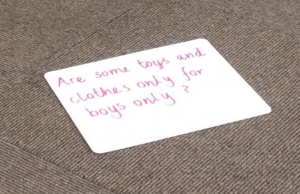

The teachers of Broadgreen Primary are not alone in their ability to believe that clothes and toys should on the one hand not be gendered, but on the other hand a child’s preferences are reason enough for transition.

The teachers of Broadgreen Primary are not alone in their ability to believe that clothes and toys should on the one hand not be gendered, but on the other hand a child’s preferences are reason enough for transition. ‘Is it okay to change from a girl to a boy?’ the children are asked, after reading the book.

‘Is it okay to change from a girl to a boy?’ the children are asked, after reading the book.

Later that month, Bergdorf angered women by writing an article for Grazia magazine where, in an ultimate act of mansplaining, he accused women of doing feminism ‘wrong’ and complaining that women did not see him as a real woman. ‘A woman is more than a vagina,” he complained, going on to call pink pussy hats ‘a well-intentioned yet misguided symbol of women’s equality’.

Later that month, Bergdorf angered women by writing an article for Grazia magazine where, in an ultimate act of mansplaining, he accused women of doing feminism ‘wrong’ and complaining that women did not see him as a real woman. ‘A woman is more than a vagina,” he complained, going on to call pink pussy hats ‘a well-intentioned yet misguided symbol of women’s equality’. In May 2018 Bergdorf said he was ‘honoured’ to appear in a photoshoot for soft-porn magazine Playboy.

In May 2018 Bergdorf said he was ‘honoured’ to appear in a photoshoot for soft-porn magazine Playboy. The NSPCC was formed in 1889, in a time when animals had more rights than children, having campaigned to get

The NSPCC was formed in 1889, in a time when animals had more rights than children, having campaigned to get  Childline was started in 1986 by Esther Rantzen in response to a television program about child abuse. The idea of a phoneline where children could ring to report abuse or for someone to talk to was revolutionary and without doubt it has changed lives for the better.

Childline was started in 1986 by Esther Rantzen in response to a television program about child abuse. The idea of a phoneline where children could ring to report abuse or for someone to talk to was revolutionary and without doubt it has changed lives for the better.

In case you haven’t come across it before, Gendered Intelligence’s advice for teens in their

In case you haven’t come across it before, Gendered Intelligence’s advice for teens in their  Hang on – your gender expression makes you trans? You mean, like, playing ballet or football? Having long hair or short hair? Oh, of course, that was the bit about wanting to dress a certain way or read certain books.. wait.. if I’m a boy and I read ‘girls’ books’ I’m trans?

Hang on – your gender expression makes you trans? You mean, like, playing ballet or football? Having long hair or short hair? Oh, of course, that was the bit about wanting to dress a certain way or read certain books.. wait.. if I’m a boy and I read ‘girls’ books’ I’m trans?

Angelicat is a meme created by a woman after she read about ‘angeligender’ on Tumblr “A gender found only among angels that is hard to describe to non-angels. For godkin and angelkin only.”

Angelicat is a meme created by a woman after she read about ‘angeligender’ on Tumblr “A gender found only among angels that is hard to describe to non-angels. For godkin and angelkin only.” Just when you think things can’t get any more absurd, the NSPCC appoints Munroe Bergdorf as a Childline representative for LGBT youth.

Just when you think things can’t get any more absurd, the NSPCC appoints Munroe Bergdorf as a Childline representative for LGBT youth. “I’m excited to have the opportunity to let more kids know that they are not alone in their how they feel. There are people who care, people who can help and people who have been through the same things as you, so PLEASE don’t suffer in silence.”

“I’m excited to have the opportunity to let more kids know that they are not alone in their how they feel. There are people who care, people who can help and people who have been through the same things as you, so PLEASE don’t suffer in silence.”

In November 2017 Munroe sparked controversy and showed a blatant disregard for child safety protocols by tweeting that trans-identified children should contact him directly by private message. Several young people tagged him and were told ‘DM me‘. The next day he posted again telling kids to contact him via Instagram, concluding ‘you gotta big sister here, always’.

In November 2017 Munroe sparked controversy and showed a blatant disregard for child safety protocols by tweeting that trans-identified children should contact him directly by private message. Several young people tagged him and were told ‘DM me‘. The next day he posted again telling kids to contact him via Instagram, concluding ‘you gotta big sister here, always’. I tweeted at the NSPCC Director of Children’s Services but received no reply.

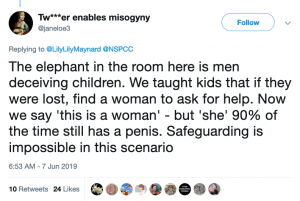

I tweeted at the NSPCC Director of Children’s Services but received no reply. “The elephant in the room here is men deceiving children.” wrote one Twitter user. “We taught kids that if they were lost, find a woman to ask for help. Now we say ‘this is a woman’ – but ‘she’ 90% of the time still has a penis. Safeguarding is impossible in this scenario.”

“The elephant in the room here is men deceiving children.” wrote one Twitter user. “We taught kids that if they were lost, find a woman to ask for help. Now we say ‘this is a woman’ – but ‘she’ 90% of the time still has a penis. Safeguarding is impossible in this scenario.”

Could it be that the flurry of complaints, both on and off social media – I know, for example that both my sister and my friend Anna had emailed the NSPCC- had resulted in the NSPCC reconsidering their decision?

Could it be that the flurry of complaints, both on and off social media – I know, for example that both my sister and my friend Anna had emailed the NSPCC- had resulted in the NSPCC reconsidering their decision?

On the left is the Merrriam-Webster dictionary definition of pornography. For examples of Bergdorf’s photoshoots, see again the header picture for this article.

On the left is the Merrriam-Webster dictionary definition of pornography. For examples of Bergdorf’s photoshoots, see again the header picture for this article.