They were hush-hush arrangements. We didn’t want the Tate to suspect that there would be a protest. Meeting in a pub on the south bank of the Thames beforehand, we arrived at the gallery in small groups of two or three.

We were there to watch a short film called ‘What is a Woman?‘ by Norweigian film maker Marin Håskjold, in the Starr Cinema. At the end we would stand up at the front and unfurl our hidden banners. One of us would call out, “What is a woman?” and the others would reply, “An adult human female! Art without freedom of speech is propaganda!”

It was a cold but bright afternoon on the Southbank.

Once in the Tate, we milled around in small groups before making our way to the cinema, where tickets could be collected half an hour before the film began.

There was a bit of time to kill before I could pick up my ticket so I went to check on the tiny snail perched on the top of Matisse’s painting of the same name.

I hadn’t seen it since pre-Covid times.

TATE Film, so the website tells us, is focused on ‘expanding the dialogue between art and the moving image’.

This idea of valuing dialogue and communication was continued on a poster outside the cinema.

“Marin Håskjold’s short film focusses (sic) on a discussion that arises in a women’s locker room when a trans woman is asked to leave. While suggesting some of the everyday encounters experienced by people who are trans and non binary, the film opens up space for reflection and dialogue. Followed by a conversation with the artist.”

But why protest?

It is important to be clear about the reasons behind our protest. The issue here was not with the film maker but with the Tate. On one hand we were told that the film would ‘open up space for reflection and dialogue’, but on the other, the usual Q&A session which generally follows a short film showing had been replaced with a conversation with the artist.

It is important to be clear about the reasons behind our protest. The issue here was not with the film maker but with the Tate. On one hand we were told that the film would ‘open up space for reflection and dialogue’, but on the other, the usual Q&A session which generally follows a short film showing had been replaced with a conversation with the artist.

That Håskjold was given the opportunity to have her film shown at the Tate is an achievement of which to be proud. The suggestion that both side of the gender debate are explored, either within this film, or in Tate films, events and exhibitions generally, is unsubstantiated.

As one of the protestors told me:

“If the Tate genuinely want to show all sides, then they’ll platform work by a gender-critical feminist film-maker too. Vaishnavi Sundar would be an excellent choice.”

There was a flurry of arrivals as the tickets were distributed. I overheard a woman ask if there would be a Q&A after the film and she was initially told yes. A few minutes later the curator came down and told her that on this occasion there would be no Q&A but there would be a conversation between herself and the artist.

I’d estimate about two hundred people collected tickets, mostly older students. I thought the cinema would be packed when we took our seats, but once everyone settled it was about three-quarters full.

Let the film begin

Women take their seats at the front of the cinema.

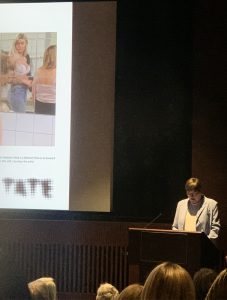

The film was introduced by the curator, a woman called Valentine Umansky. I initially had her pegged for a post-grad enby, but I looked her up and I was wrong. She’s older than I thought and has a pretty impressive career behind her already, which makes the whole ‘no debate’ thing that followed even more irritating.

Art as a safe space

Umansky took the stage and opened by telling us:

“One note before we start, which is really important actually- we should probably do this every screening but we don’t- I just wanted to preface this by saying we consider the Starr Cinema to be a safe space, so we will not tolerate any kind of abuses there of any sort and I think it’s really important to start the screening with that.”

Remember that correctly sexing somebody is considered to be abusive in such a ‘safe space’. So there goes that ‘reflection and dialogue’ that we weren’t going to be allowed anyway. Umansky says she doesn’t usually make this announcement: so why now, on this and only this subject? Why should Umansky and a cinema in an art gallery feel the need to declare itself a ‘safe space’? Should we necessarily feel psychologically ‘safe’ in the presence of art?

“Right after the 14 minute film we (Umansky and Håskjold) will have a conversation – just together – to give a bit more context around the film.”

So here we are, preparing to watch a film which is being shown with the ostensible intent of both ‘expanding the dialogue between art and the moving image‘ and ‘open(ing) up space for reflection and dialogue’ . Yet for all the repetition of the word ‘dialogue’ we have been told- twice- that no debate will take place.

Umansky thanked several teams and spoke of the “really strong support we’ve received from our LGBTQIA+ network”.

So much becomes clear once you realise that the Tate is- of course- a Stonewall Diversity Champion. Staff at the Tate are encouraged to join the LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, Intersex, Asexual and related communities) Network. Job applications are welcome from all regardless of ‘age, disability, gender identity or gender expression, race, ethnicity, religion or belief, sex, sexual orientation or any other equality characteristic’. The protected characteristic of sex does not come so near the end of the Tate’s list for nothing: work by women is consistently under-represented in Tate collections. As Helen Gørrill pointed out in the Guardian back in 2018:

“While Tate appears to have a 30% cap on the collection of female artists, its allocation of annual budget is even worse, with as little as 13% spent on works by female artists in recent years. This perpetuates the dominance of male artists in the collections and suppresses the value of women’s work.”

Back to the cinema

Håskjold told us that the idea for the film sprang from the discussion in Norway about simplifying the laws concerning changing legal sex.

Håskjold told us that the idea for the film sprang from the discussion in Norway about simplifying the laws concerning changing legal sex.

“As time has passed… the discussion around gender has been more and more polarised so I feel like it’s really important that we discuss this in a way and meet each other… I’m getting more and more convinced that it’s important to talk and listen to each other regardless of our differences.”

I wonder whether Håskjold would have been open to the idea of a Q&A? Was it the Tate that scuppered that idea? I wonder if she has really explored some of the ideas that critique gender and queer theory? Does she think males also belong on women’s sports teams and in their prisons?

So, as the film is supposed to inspire reflections and dialogue, I thought now was as good a time as any to share my views. I wanted to see it a second time before writing a review and as it isn’t available online free, I purchased it for £3.99. You can do this here if you are so inclined. You can see a trailer on YouTube, here.

![]()

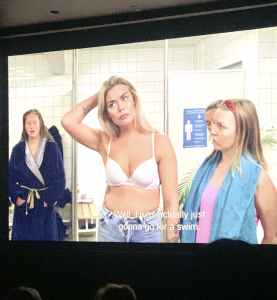

The lights go down. The film is set in the women’s changing room at a leisure centre. For the first 90 seconds we hear the sound of running water. Three women focus on washing as they shower naked, or semi naked, in a communal shower area.

The lights go down. The film is set in the women’s changing room at a leisure centre. For the first 90 seconds we hear the sound of running water. Three women focus on washing as they shower naked, or semi naked, in a communal shower area.

The screen goes black and we hear a woman’s voice. We do not see the ‘transwoman’ nor hear him being asked to leave; we join our characters in the middle of a conversation.

There were no introductions, so I make no apologies for giving the characters the names I gave them in my head while I was watching the film for the first time.

“If I saw you naked, would you be a complete woman then?” asks Evil TERF, who is dressed in a black top and tracksuit bottoms.

She faces Blokey and Blokey’s Mate across the changing room.

Blokey’s Mate is small and blonde. She wears tracksuit bottoms, a headband with a bow or red roses and a pale pink spaghetti strap top.

Blokey wears jeans, a white bra and a blonde wig. He says very little, wide-eyed and vulnerable, somewhat in the manner of an oversized fawn. He is very ‘pretty’ in a slightly pornified Barbie doll manner. For someone popping into their local pool for a swim, he’s wearing an awful lot of make up.

“What do you mean?” asks Blokey, all innocence, dropping his eyes and turning slightly away.

“You can see she’s a woman,” replies Blokey’s Mate. We see in the changing room mirror that she gesticulates in the area of his chest.

“You can see she’s a woman,” replies Blokey’s Mate. We see in the changing room mirror that she gesticulates in the area of his chest.

“Do you have a penis?” asks Evil TERF, having been forced to elaborate.

There is a moment’s stunnned and horrified silence.

“That’s none of your business!” exclaims Blokey’s Mate, in feigned shock.

“It is,” explains Evil TERF. “Many women would be uncomfortable seeing a penis in here. Think of women who have experienced abuse.”

“We are not going to dangle any penis in their faces,” retorts Blokey’s Mate.

Like several others points raised in ther film, the genuine concern raised here falls by the wayside, as if it the feelings of those women are not even worthy of consideration. They are given a voice but that voice is not acknowledged. Instead it is dismissed with an image that manages to be both ludicrous and intimidating. This is a pattern repeated throughout the film, which is sharply shot and polished, but never actually addresses any of the genuine problems raised by the presnce of Blokey.

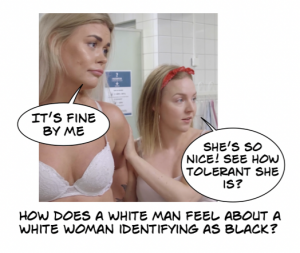

Evil TERF mentions pregnancy and periods, and then asks “What if I identify as black?”

Blokey smiles and nods, “It’s fine with me.”

Blokey smiles and nods, “It’s fine with me.”

“She’s so nice!” gushes Blokey’s friend. “See how tolerant she is?”

Is tolerance a virtue to be valued above all else? Is it really a white man’s place to give his blessing to trans-racialism? What else are we supposed to tolerate? Can you guess?

Evil TERF raises again that there may be women who don’t want penises in their changing rooms.

“They can look elsewhere,” retorts Blokey’s Mate, who seems to have lost her respect for tolerance as quickly as she found it.

A short-haired woman comes in and goes to change out of shot. A woman with a toddler arrives from the pool and asks what’s going on. Blokey’s Mate tells her indignantly, “Everyone is allowed to be here.”

But WHY is ‘everyone allowed to be here’? What’s the point of a female changing room if anyone in a bra is allowed to be there? This was not discussed.

“She’s way more womanly than me!” adds Blokey’s Mate.

“She’s way more womanly than me!” adds Blokey’s Mate.

Blokey stands silent throughout most of this, occasionally lightly touching his hair or his shoulder or chest.

“Are we going to decide based on our looks? Does it matter how you look?” asks Short-haired Woman suddenly, and Blokey’s Mate looks embarassed and agrees that we should not and it doesn’t.

“But you’re born either a woman or a man,” puts in Swim Mum. Her toddler runs naked through the changing room, so we clearly see that yes, there is already one penis present in the changing room.

Swim Mum mentions an ‘enby’ child at the school where she works and the confusion it causes.

“If she can communicate that as a child you should be able to meet her as an adult,” replies Short-haired Woman, with a Hard Stare. Which sounds good initially, but means… well… what, exactly?

Swim Mum rants about feeling judged, and worried parents, and finally bursts out, “can we just relax and calm down!”

Aha! See? Swim Mum is just another hysterical scary fascist wine mom after all.

“Can’t we just agree that there’s nothing left to discuss?” asks Blokey’s Mate. Blokey has finally encapsulated his ample bosom with what looks like a large tea towel.

“It’s not that simple,” says Evil TERF. “You need more than a dress and make up to be a woman.”

She is next to become agitated, pointing her finger and raising her voice, talking vaguely and somewhat incoherently about how men should be allowed to wear dresses and if only people could look as they like. Something may have been lost in translation. Blokey’s response is to drop the tea towel and once again reveal the now familiar snow-white bra.

“I am here because I am a woman.” replies Blokey profoundly.

What could possibly happen next? Did you guess? Short-haired Woman speaks up.

“I’m a woman biologically but I don’t know what I feel like.”

There’s no avoiding the inevitable conclusion we should have drawn the moment a short-haired, small-breasted woman entered the room – yes, she in indeed of the Enby tribe.

“I can feel like a man. I can feel like a woman.”

“How,” I want to yell at the screen, “can you possibly know how a man feels when you’re not one?” But this and other important issues are not to be considered, either onscreen or off. After all, this is a a safe space.

“I’ve been beaten up for the way I look,” she says.

And suddenly it all feels so terribly sad: the woman who doesn’t feel like a woman because the way she imagines a woman is supposed to look and feel is personified in the form of the man in front of her.

And suddenly it all feels so terribly sad: the woman who doesn’t feel like a woman because the way she imagines a woman is supposed to look and feel is personified in the form of the man in front of her.

And both believe that there is a certain way that men and women should not only behave but actually feel.

“It’s already been decided what I should look like as a girl. What interests I should have. How I should behave, how I should dress. My entire life is already pre-determined.”

At the risk of sounding a little harsh here, no it isn’t. To a greater or lesser extent, you can say ‘no’ to those things. What you can’t say ‘no’ to is the biological implications of the body you are born into. You can’t identify out of that.

“If I don’t fit into those boxes, what do I do?” she asks.

Enby (my new name for Short-haired Woman) sounds both angry and desperate. Nobody offers an answer.

“Why can’t you just be called ‘she’?” asks Evil TERF.

“Because I want to be called ‘they’!”

Evil TERF is accused of telling people how to live their lives. Then she makes the mistake of correctly sexing Blokey.

“You tell us who we are,” accuses Enby furiously. “Exactly like the patriarchy.”

Yup, you got it. A woman who believes that women are entitled to single-sex changing facilities is doing the work of the patriarchy. When Evil TERF protests, Enby tells her, “to me these are just empty words. They mean nothing.”

Another woman comes over to see what the discussion is about.

“Whether or not I have the right to be here, because I am trans.” says Blokey, sadly.

“You have the same rights as everyone else.” she assures him fluffily.

“You have the same rights as everyone else.” she assures him fluffily.

Enby says she is offended by the words of Evil TERF and that Evil TERF is ‘brutal’. She suggests Evil TERF finds her own changing room, one just for her. Spectacularly, Enby has changed her bra completely since the last shot. She is very angry.

“I think this is getting too silly,” asserts a new arrival. She’s damn right. I am rapidly losing the will to live.

“I don’t know what I am. I don’t know what I am.” repeats Enby.

She seems distressed. Nobody dares reassure her. The room full of women fold their arms and look around at each other and her. The camera zooms in on Swim Mum and she looks, as my sister would say, ‘like a lamb caught in the headlights’.

“What do you think?” someone asks Blokey after a long silence.

“What do you think?” someone asks Blokey after a long silence.

“Well, I was actually just going to go for a swim.”

And, after throwing everything into chaos and pitting a room full of women against each other, I presume he saunters off to do just that.

Untangling the web

The shower scene at the start of the film accompanies the titles and takes up a good minute and a half, a full 9% of the entire film, so it’s safe to assume its significance runs beyond maiden/mother/crone and Melusina imagery. There is an eternal water goddess within every woman… but wait… I hear you ask “What about the men?”

The shower scene at the start of the film accompanies the titles and takes up a good minute and a half, a full 9% of the entire film, so it’s safe to assume its significance runs beyond maiden/mother/crone and Melusina imagery. There is an eternal water goddess within every woman… but wait… I hear you ask “What about the men?”

The women’s changing rooms and showers are open, so we know that should blokey so desire he could also shower naked in the communal area. Blokey’s Mate assures Evil TERF, ““We are not going to dangle any penis in their faces.” How different would the viewer feel if the opening shower scene had included a shot of Blokey washing his penis?

We are told that the action in the film occurs after a ‘transwoman has been asked to leave’. As Blokey has not left, we must assume he refused to do so. We don’t see who asked or when: no reference is made to the request having been made during the film.

I do not call Høvik ‘he’ as an act of hatred or spite, I do it because it is true. I do it because if women are to claim back our single-sex spaces then we will need to use clear language to do so.

prizes for being pretty

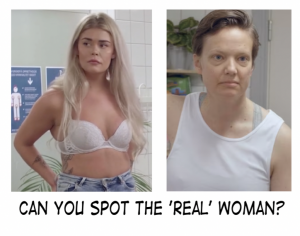

The next thing I’d address is that Mina Alette Høvik, who plays Blokey, really does not look like your average trans-identified bloke. We are all drawn to pretty faces but being a woman is not about how pretty you are, or how much you can afford to spend on plastic surgery.

Initially, Blokey’s Mate refers to how womanly Blokey looks, and that ‘you can see (s)he’s a woman’. With the arrival of Enby her position changes and she says looks don’t matter, but that idea is not explored beyond the inevitable confusion it causes everyone involved.

Access to single sex spaces should not be dependent on how pretty a man is. No wonder Enby was angry if that was the game she was expected to play. What message does it give to women who are not conventionally pretty or performative when the world is so eager to believe that they are not actually women at all?

Consider this. Let’s replace Mina with Danielle (centre). Would the women in the changing room have been so empathic? Would they have embraced tubby little D with his 5 o’clock shadow?

The film placed a lot of focus on Mina’s chest. Now instead of Mina’s pretty white push-up bra, let’s look at the bloke on the right. He’s wearing a bra too. Would he be welcome? All these men think they are women. Who will you welcome to your spaces, all, none or just the young, pretty ones?

The film placed a lot of focus on Mina’s chest. Now instead of Mina’s pretty white push-up bra, let’s look at the bloke on the right. He’s wearing a bra too. Would he be welcome? All these men think they are women. Who will you welcome to your spaces, all, none or just the young, pretty ones?

Now cast your mind back to that communal shower at the start of the film. How would those woman likely feel if they were confronted with bloke 3 naked in the open shower?

If you are only willing to admit the young, pretty ones, then it’s time to admit that supporting diversity has absolutely nothing to do with your choices. It’s time to admit that you have been taught to accept that womanhood is a costume, a feeling, a mask that a man can pick up and wear. You know what? You’ve been sold a lie.

if a person has a penis

Equating seeing a naked boy toddler in a female changing room with being exposed to the unsolicited genitals of a naked adult male is so leftfield that I’m not suprised that even this film only referred to it in passing. An adult man is not a baby. The two are not synonymous.

Equating seeing a naked boy toddler in a female changing room with being exposed to the unsolicited genitals of a naked adult male is so leftfield that I’m not suprised that even this film only referred to it in passing. An adult man is not a baby. The two are not synonymous.

Most people are unaware that the vast majority of trans-identified men choose to keep their penis. Høvik makes no secret of having undergone GRS the year after the film was released. But focusing so heavily on whether a man has or has not had his penis removed suggests that if a man has had his penis amputated he does somehow become a woman. Now I wouldn’t disagree that a man who does this has indeed shown his commitment to the idea, but that does not turn it into a reality.

I should add that it doesn’t fill me with confidence that a man is necessarily neither mad nor dangerous because he has had his penis amputated. Am I being unkind? Perhaps. I am being honest. Being nice does not seem to have got us very far.

Am I saying that all trans-identified men are crazy murderous psychopaths? No. Of course note- no more than I am saying that all other men are all crazy murderous psychopaths. But trans-identified men are still men, raised with both the biology and social privilege that entails. Studies suggest that their conviction rate for violent crime is just as high as any other men, and sixteen times higher than that of women.

The truth is that, penises or no penises, single-sex spaces should have nothing to do with gender identity. It is disingenuous to suggest that the only reason women don’t want men in their spaces is becuase they are afraid of rape – as if that shouldn’t be a good enough reason alone! More often than not it is a general feeling of discomfort and loss. We thought we had single-sex spaces, and that we were safe from centering and encountering men in those spaces. We had begun to take them for granted and now it seems we don’t have them any more. Many women feel perhaps it isn’t worth making a fuss about, they don’t want to make a scene… and nobody wants to be called a bigot, receive hate mail or lose their job.

the right sort of tolerance

Both the women willing to challenge the idea that Blokey is a woman are dressed in dark clothing. Both become agitated. While they are given the chance to raise issues, those issues are quickly glossed over and are neither discussed nor clearly articulated.

The association of womanhood with pregnancy & periods get  a throwaway ‘whatabout’ from Evil TERF, but the importance of biology is never addressed, as she skips on to asking ‘what if I identify as black?’

a throwaway ‘whatabout’ from Evil TERF, but the importance of biology is never addressed, as she skips on to asking ‘what if I identify as black?’

As mentioned earlier, Blokey is fine with this.

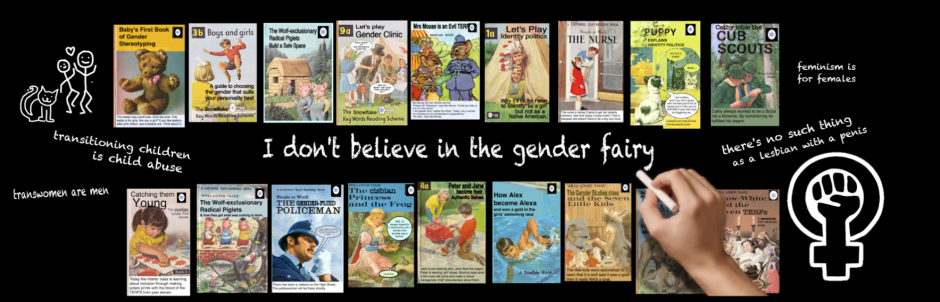

“Tate,” asks Art Not Propaganda. “Is this sort of racism really what you think you should be platforming?”

“No Muslim women in the changing room discussion of course.” observed Twitter user Di Hunt. “They are not even allowed to enter now that there is a male in there.”

There are many reasons why a woman or a girl might not want a man in their sinmgle-sex changing room.

The safety and concerns of all these women are dismissed, by a woman, with the flippant, ‘We are not going to dangle any penis in their faces’ and ‘they can look elsewhere.’ Her trans friend is ‘so nice… so tolerant...’ but this is a tolerance that is limited towards certain groups.

After careful reflection I would interpret the message of the film as something like this.

“Be nice. He is a woman because he says he is and he looks like a woman and if you are a woman but you don’t look like a woman then maybe you’re not a woman although of course you could be a woman because while it really matters what you look like it also doesn’t really matter at all and anyway we are all exactly what we say we are even if we don’t know what that is. So be nice.”

You’re welcome.

Back to the cinema

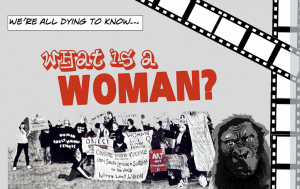

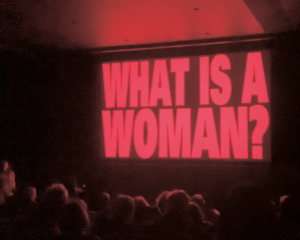

Back at the Starr Cinema, the film was drawing to an end. We knew it would end when the words ‘What is a Woman?’ came up in red lettering on the screen. And then suddenly, there they were.

Back at the Starr Cinema, the film was drawing to an end. We knew it would end when the words ‘What is a Woman?’ came up in red lettering on the screen. And then suddenly, there they were.

The audience clapped and as the applause began to die down, the women leaped up, turned and faced the still-seated auditorium.

“What is a woman?” called out one, in a loud, clear voice.

“An adult human female!” replied the others, in unison. “Art without freedom of speech is propaganda!” They stood there a moment, banners aloft, and then turned and walked up the steps to the left of the screen and out of the cinema.

“What the fuck, are you…” one young woman called after them, and I thoght i heard a whisper of ‘transphobes’but the voices trailed off as they realised the women were not looking for confrontation but simply leaving in silence. A murmur ran through the audience and clusters of conversation broke out.

And that’s when I realised that I’d pressed the button on my phone at the wrong time and totally failed to film any of the actual protest… gulp… which means this is the only photo I have to show you.

The last of the women leave the cinema after the protest

(I should say that even though people must have been a bit disappointed that I messed that up, nobody had a go at me and everybody told me not to worry. Which was very nice of them because obviously I felt like a right idiot.)

we’re just taking a break to care for our mental health

Most of the women involved in the protest left, but a few of us stayed behind to hear the conversation between Håskjold and Umansky. There was a break of a few minutes before the conversation started.

“Just a quick note that we’re taking a couple of minutes to digest what just happened,” Umansky told us brightly, “and then we’ll come and have a conversation… we’re just taking a break to care for our mental health and we’ll be back.”

The conversation

Their mental health having re-established its equilibrium, Håskjold and Umansky took their seats.

Håskjold, who is also a photographer and studied at the Nordlands School of Art and Film, said that she prefers to define herself as an artist rather than a filmmaker as it is less specific and people have less restrictive expectations of her work.

Throughout the conversation they talk about Håskjold’s inspirations, some of her other films and the element of discussion and recurring themes within in her work. Below are just some snippets of the discussion.

Håskjold says the film is a bit like a documentary because it’ based partly around comments she’s seen on facebook and social media.

“Why do these people mean what they mean?” she asks. “Why are they so angry? … what are they scared of? What are we scared of?”

“It’s presented from a very multi-persepctival point of view,” says Umansky of the film. “where you alternate between various viewpoints on the question.”

She went on to call the film ‘open ended’, ‘not too directive’ and to claim Håskjold leaves the end of the film “really open for the viewer to make up their own mind”.

Had we just watched the same film? I found this perspective very strange, as to me the film had seemed extremely biased. If Håskjold had done even a small amount of research she wouldn’t be asking why women were feeling angry and scared about the presence of men in their spaces.

“I don’t want to make propaganda, in a way. I just want people to get a grip of this. How the news is presenting it, the debate is, like, really harsh and polarised… People are really angry and calling a transwomen a man on national television: that’s not… I feel this discussion is really important to have but we have to have it in the right way… we can’t have it when people don’t want to join the conversation.”

“I don’t want to make propaganda, in a way. I just want people to get a grip of this. How the news is presenting it, the debate is, like, really harsh and polarised… People are really angry and calling a transwomen a man on national television: that’s not… I feel this discussion is really important to have but we have to have it in the right way… we can’t have it when people don’t want to join the conversation.”

“I also agree that we should have this conversation,” adds Umansky, who, let’s remember, has made it very clear to the audience more than once that there is to be no discussion. “That’s why we screened the film and you’re here… to my understanding the main concern of the women that were here tonight was that their voice wasn’t heard in the film, whereas I can’t find a single voice that is not heard.”

While Umansky had no warning about the protest and was not to know that it was specifically concerned with the Tate’s refusal to platform ideas concerned with women’s single sex spaces and rights, this claim seems astonishingly naive if not willfully ignorant. She couldn’t find a single voice that wasn’t heard in the film?

Of the protestors she said, “the Tate is a large institution and I understand that in a sense everybody can feel like it’s a public institution so they have a space to speak. So maybe that’s why they took the stage but in a way I think their voice was already in the film, in a sense.”

Håskjold told us a little more about the actors. She met two of them during her studies and describes them as “the woman that is playing the- sorry for the word – TERF, and the non-binary character.” For the main character, she said, it was more important that the part should be played by a transwoman than an actor. She wanted people to watch the film and ‘not feel alone’.

When she said the word ‘TERF’ a chorus of embarassed little giggles ran around the cinema. They say all voices and concerns are heard in the film and then they call women TERFs, and they laugh.

Back to the protestors!

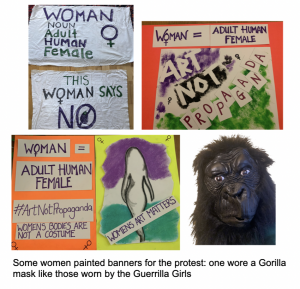

The protestors were back outside, celebrating; breathing in the fresh riverside air and being photogaphed. @WRNWoman allowed me to share her photos here. The woman on the right is wearing a gorilla mask in tribute to feminist art critics the Guerilla Girls.

I asked some of the women who took part in the protest to give me their thoughts.

“The film was very clearly favouring one side of the argument.” Charlotte observed. “The transwoman character being ‘bullied’ was a passive, vulnerable blonde with big breasts which were on full display, since they were the only one to spend most of the film in their bra. When the non-binary character asked how the others knew she was a woman, they all appeared flummoxed even though it was obvious.”

“It was all very “how could you be against this? Look how beautiful she is and she doesn’t show ‘her’ penis.” said another.

“My reason for being at this protest was to ensure that our young girls continue to have female role models to look up to. The Arts is a passion of mine and the Tate is betraying current and future generations of female artists by making it clear that only woman-hating art is now acceptable.”

“I’ve never protested over anything before,” said a woman who wished to remain anonymous.

“I’ve never protested over anything before,” said a woman who wished to remain anonymous.

“This was the first time and it honestly felt scary. But I felt it was so important to stand up, both metaphoricaly and literally. Our words are being taken away and their meanings changed and twisted… and it makes me sad and angry that we cannot even discuss such an important issue openly, with all sides of the issue fairly represented without being threatened and our livelihoods lost. So I feel my only option is to anonymously protest, to try to protect our words and all women’s rights.

And I’ll add that as we walked out of the Starr cinema, the atmosphere and the comments from the audience (something like fuck off terfs, I can’t remember the exact words) was quite frightening… but I’m glad I did it. I hope my daughters’ daughters will also be glad we did.”

“Marin Håskjold and the Tate argue that the film included “multiple perspectives”, but this belies the fact that all of these perspectives were heavily filtered through the filmmaker’s own.” SistaRealista told me. “Håskjold made directorial choices that make it clear she believes a transwoman – a male, with a penis – should be allowed to openly change in a women’s changing room.”

the most significant question of our time

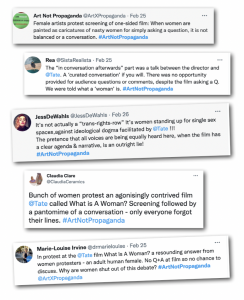

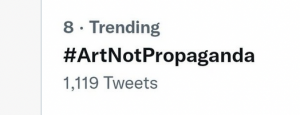

The protest definitely caused a stir. That night the hashtag #ArtNotPropaganda was trending on Twitter and we were delighted to see that the protest had made the Telegraph, both online and in the newspaper. The article is archived here.

The protest definitely caused a stir. That night the hashtag #ArtNotPropaganda was trending on Twitter and we were delighted to see that the protest had made the Telegraph, both online and in the newspaper. The article is archived here.

“We are here to say loudly and proudly to Tate Modern that women are adult human females,” a spokeswoman for the protestors told the Telegraph. ““Many of us work with galleries and in the arts, and we know that stating this simple fact can lead to loss of work and harassment.“

“It is not our intention to ‘cancel’ Håskjold’s film – we think artistic freedom is important. But the public deserves better than to only be shown one side of what is the most significant question of our time.”

The Tate responded by saying the film ‘does not propose one perspective on the question of womanhood, but instead considers multiple perspectives,‘ adding of the organisation itself, ‘as always, we aim to be inclusive of all perspectives’.

I leave the last word to some Twitter voices.

But I somehow suspect this might not be the last time we see adult human female activity in the art world…