Why are so many women scared to speak out about gender politics?

Why are so many ‘gender critical’ women scared to use their own name?

By the time I was ready to tell the story of my daughter’s trans-identification and desistence, I felt certain of one thing: our anonymity was essential. My daughter Jessie was just sixteen, newly desisted and starting college. I did not want fingers pointed at her, I did not want her identified. She was a child, not a pawn in a game of politics. If she was to remain anonymous, so must I.

I’m not sure why I chose the name Lily Maynard. It sounded sort of, well… normal, yet it rolled off the tongue easily. I didn’t really think about it much at the time. After all, I was only going to use it to sign off that one article, wasn’t I?

But that one article wasn’t enough. Jessie was out of the woods, but my indignation spread to include the hundreds of other children who were being told yes, their bodies were ‘wrong’ and they could be somehow ‘fixed’ by lying about their sex, blocking their puberty and, eventually, modifying their primary and secondary sex characteristics. In parenting groups on facebook I saw scores of parents suddenly posting about their own ‘transgender’ and ‘non-binary’ children. It was all so harmful and so bloody sexist! To accept one special child as trans or non-binary one has to block other children within the binary. There is an immediate confusion of sex and gender which I am to this day astonished that so many people can’t see past. My indignation grew to horror and fury as I learned about the erosion of women’s safe spaces, shortlists, public toilets, changing rooms, sports teams, refuges, prisons.

In January 2017 I joined Twitter, and a few months later I started my blog, which became surprisingly popular. It was censored and then shut down by WordPress because of complaints by transactivists, but was born again here. Some of my longer articles, or records of events, take weeks of research, notes or transcription. It’s hard work and it’s unpaid. It seems to me that, of course, it is possible to be anonymous and still make a difference.

I’m also politically active ‘as myself’. I’ve been involved in IRL Man Friday and Fair Play for Women campaigns. I’ve filled in consultations and surveys. I’ve spoken with events organisers, educational establishments and my MP (who doesn’t give a shit) about the importance of women’s spaces and the dangers of transitioning children. I am a proud compatriot of Stickerwoman; I’ve stitched banners for protests and waved an ‘Adult Human Female’ flag on women’s marches. When I post ‘gender critical’ articles or ideas on my personal Facebook or Instagram accounts the posts are frequently met with silence, (unlike pictures of my cats, kids and travels which are met with enthusiastic ‘likes’).

On the occasions that I’ve been interviewed for newspapers or magazines, I’ve been asked- often more than once- for photos of myself or Jessie to go alongside the article, and I’ve always said ‘no’. I’ve turned down the chance to be in documentaries and to appear on television on more than a handful of occasions. I did give an interview to Sonia Poulton for her forthcoming documentary – but I kept my back to the camera.

IRL me is nowhere near as vocal as Lily, and even though my daughter is now many years out of the woods and off at university, IRL me is still a little scared to ‘come out’ as Lily. I’ve received hate mail and threats of violence. I can see both sides of this coin.

Online and offline I hear women saying, ‘I’d like to speak up but I don’t dare… I’m worried I’d lose my job… or my husband would lose his job… there’s a trans child at my kids’ school… I’m worried people will hate me… I’m worried people will bully my kids… I’ll lose all my friends… I don’t want to be seen as transphobic…’

Some are dismissive of these women, yet people don’t always feel able to stand up for themselves and speak their truth. We are human and to a greater or lesser extent humans have a strong sense of short-term self-preservation, even if it is sometimes misguided in the long run. For every woman willing to throw herself under the King’s horse, there are hundreds who just don’t get involved in politics, whose sphere is at home or in the workplace. Some of us are fearless, some of us are not. Some of us feel the fear and do it anyway; some of us are bound by seemingly impossible circumstances. This is human nature.

How many tyrants could have been overthrown if all the people they were oppressing had risen up en masse- at exactly the same time- with a roaring ‘no’? How many lives could have been saved if entire armies had refused to fight unjust wars? But we are not all selfless heroes, ready to die for our cause. While there’s no doubt there can be hefty consequences to speaking out, there’s also no doubt that speaking out is what is needed.

If the analogies seem a little grandiose, consider the following.

Attacks on women who speak out

Since I opened my Twitter account in January 2017, saying men cannot become women and/or children should not be transitioned has resulted in women being sacked, receiving rape and death threats, having their apartment door urinated on, being punched in the face (and forced by a judge to refer to the man that did it as ‘she’). Women have been interviewed under caution by the police for criticising the castration of 16 year olds and had pictures of their children posted online; others have had their home addresses published. The young founder of a company making bras specifically for pubescent girls was slated online for because an employee tweeted ‘we don’t feel that growing boys need bras’. ” I’m sorry.. I’m so, so sorry.. I sincerely apologise… again, I’m so sorry.” she tweeted desperately. At least two girl guiding leaders have been expelled for saying ‘female is not a feeling’ and objecting to policies allowing boys who ‘identify as girls’ to join. A Woman’s Place meeting venue in Hastings received a bomb threat for planning to discuss gender. Teachers have been sacked for ‘misgendering’ female pupils who believe themselves to be boys in both the USA and the UK. Transactivists threw smoke bombs outside the offices of a London newspaper after it published an advert from Fair Play for Women stating ‘Think about it. Choose Reality‘.

I could go on. Remember, all these incidents have happened in the last thirty two months.

Actually, I will go on.

Lesbians have been banned from attending Pride marches for saying ‘lesbians don’t have penises‘. Transactivists wearing balaclavas and masks blocked a philosopher’s entry to a meeting in Bristol, screaming ‘Nazi’ in her face and trapping her in a stairwell. A rape crisis centre with a ‘women-only’ policy had a dead rat nailed to the door of its offices and the slogan ‘KILL TERFS TRANS POWER’ scrawled across its windows. The San Francisco library hosted an art exhibition consisting of barbed-wire enshrouded baseball bats, axes, and T shirts stained with fake blood bearing the legend ‘I PUNCH TERFS’. Women have been kicked out of the Labour Party for objecting to men on all-women shortlists and the Women’s Equality Party for saying ‘sex is a biological reality’. A woman having a quiet drink was told to leave a pub for wearing a T shirt saying ‘Woman- Adult Human Female”. Two women in Canada were evicted from a homeless shelter for objecting to the presence of a man (who claimed to be a woman). A woman was arrested in front of her young children and shut in a cell for seven hours for repeatedly ‘misgendering’ someone on Twitter. Her court case is happening as I write.

This is very far from an exhaustive list.

The truth isn’t complicated

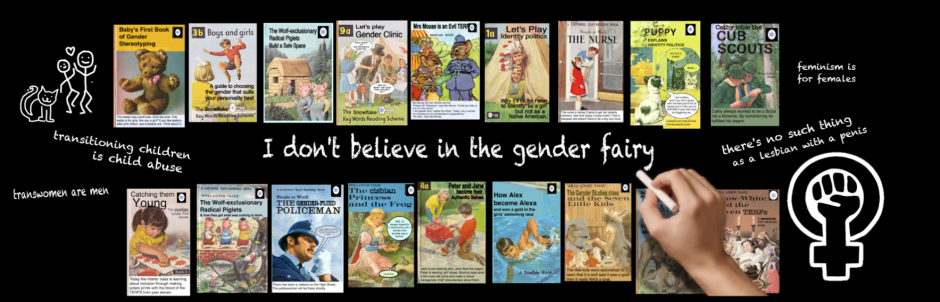

So maybe it isn’t so surprising that so many women are scared to say that they know jolly well that there’s no such thing as a gender fairy popping culturally gendered brains willy-nilly into human bodies.

Thirty years ago such an idea would have been met with scepticism. Not because people were more cruel, ignorant, bigoted or hateful then, but because we were starting to build a society more aware of the confines of sexism and beginning to accept that same-sex attraction was a fairly commonplace thing.

The operative word there is ‘sex’. If we replace sex with gender, there can be no same sex attraction. There can be no sexism. If we say we believe lesbians can have penises, lesbians no longer exist. The word ‘lesbian’ takes on a completely different meaning. If we decide that woman and man are feelings, that they are no longer biological descriptors, the words ‘woman‘ and ‘man‘ take on completely new meanings. The new ideology suggests that if we are truly, deeply discomforted by the oppressive gender stereotypes that enshroud our sexed bodies, we can just identify out of them. Our oppression becomes our own fault and our own responsibility. This is, of course, entirely untrue.

We are all born babies. Male babies or female babies. No long hair or short hair or pink or blue clothing, or tutus or hormones or surgery can ever, ever change that. A child cannot begin to understand the implications of this mass gaslighting. And nobody is ‘cis’. It is a ridiculous concept. Anorexics don’t demand the rest of us go round calling ourselves ‘kanonikósorexic’ (yes, my Greek is undoubtedly faulty but you get the point). ‘Cis’ demands most of us stay in a box so a special few can jump out.That is not progress.

As for ‘preferred pronouns’: pronouns are used when other people talk about you. Pronouns don’t describe your inner feelings and you don’t get to control the language of others. So no, you don’t have the right to choose ‘your’ pronouns or make them up: they’re about you, they don’t belong to you.

Just a little bit of analysis and this whole house of cards comes tumbling down.

As KF said on Twitter “I’ve been living in a female body for 73 years and I don’t know what it means to think like a woman. I only know what it means to think like me.“

Voices from the battlefield

I spoke to some of the women who have been vocal about speaking out on the subject of gender politics and trans-ideology. I told them I was writing a piece about speaking up and not speaking up, and attacks from transactivists, and asked would they mind ‘giving me a quote’.

These women are all based in the UK and have very different ideas and approaches. Many of them disagree on the best approach to confronting this attack on women and children, but none of them are scared to speak or be heard. Here are their replies to my request.

You can click on a name to discover more about each woman and/or the organisation she is involved with.

Hannah Clarke

I speak in my own name. It was a bit of an odd journey to it for me – when I started my husband asked me not to use the family name (it’s quite unusual) so I spoke out using my maiden name. I moved back to using it exclusively very shortly afterwards, as I’d always felt uncomfortable being Mrs HisName. I get a lot of flack from TRAs for using a fake name – my own name. Oddly they also have a go at women for using fake names when they use their married names. Seems that whatever we do we can’t win. I don’t work, and I don’t have children, so I have very little to protect in speaking out publicly against the might and spite of the transcult. Seeing how they mobilised themselves to find out my former name, and then publish details about where I live, about my family (one TRA followed my mother on twitter – an odd, but clear, act of harassment) and try to find out all they could about me was insane. Having a photo shared by my ski coach from a holiday in 2012 was bizarre in the extreme and pretty intimidating. It showed that they have no respect for any boundaries. Other members of the groups I’m involved with have had their employers contacted: had the schools their children attend shared online; had their addresses shared by TRAs. It’s frightening – these people are actively putting our safety at risk and doing so because we hold a different opinion from them. I completely understand why any woman uses a pseudonym. I kind of did to start with (even though it was my old name) but I reclaimed it because I wanted it back. Never feel bullied to do anything you don’t want to. Your boundaries are yours to set and for others to respect. Maybe, when the power of the transcult has diminished more women will be able to speak out in their own names without fear. Until then they must do what they can to keep themselves safe.

Maria Maclachlan

I never sought a public profile but, given that within hours of the assault on me, trans activists were rewriting the narrative and presenting me as the aggressor, I didn’t feel I had a choice but to speak out. I still think it’s ridiculous that I have to defend myself against a deluge of lies two years later but I will never stop. How they’ve treated me, how they treat other people and the terrible impact that trans cult ideology has had on women and children, I couldn’t in all conscience stay quiet. Doing so has taken it’s toll on me – I’ve lost income, friends and my once strong faith in humanity. It’s also had a negative impact on my health but, on the plus side, so many women have thanked me for standing up to the bullies and have been inspired to stand up alongside me. I believe there are women who are seriously at risk of losing their livelihoods if they go public in their criticisms of the cult. Look at what happened to Spinster founder M.K. Fain, who lost her job because of an article she posted on Medium. But I know – and I hate to say it – some women are staying quiet because, although agree with us, they want an easy life. They won’t lose their jobs but they don’t want to fall out with work colleagues and friends and it saddens me that they can’t find the courage to speak out when doing so could make a difference.

Kellie-Jay Keen-Minshull aka Posie Parker

Trans activists confirm time and time again the compulsive and obsessive nature of their hatred for women by attacking us. When I was doxed or when my children’s photos were put online it just reinforced that many of these activists are just rebranded men using male violence and intimidation to frighten women.

Maya Forstater

Maya suggested I quote the piece attached to her ReSisters picture.

“I spoke up because I believe we all have a responsibility to use our voice in whatever way we can. We all pick our battles, but sometimes they pick us. I am fighting on because I don’t want my story to be a cautionary tale about the high personal cost to women of having the courage to speak up, but instead to try to make it a win for freedom of thought, belief and expression, and for the heart and soul of the institutions that underpin an open society.”

Heather Brunskell-Evans

The more I have been personally threatened, the more attempts to silence my voice, the more that public institutions and political parties -including, irony of ironies, the WEP -attempt to shut down open debate about the politics of gender identity and the impact on women, the more I realise how important it is to feel the fear but still stand firm, just as our forebear feminist sisters did.

Venice Allan

My life has completely changed because I have publicly questioned transgenderism. I’ve lost friends, been suspended from the Labour Party, excluded from local politics, smeared in the press, lifetime banned from Twitter and I nearly lost my job. I completely understand why people are afraid to speak up and nobody should be shamed into a position of vulnerability. There are so many ways to fight this dangerous ideology.

I understand why some regular women stay anonymous for their safety and sanity. What pisses me off are the celebrities/politicians/journalists who agree with us but are not prepared to risk their reputations. They are worse than the ones who actually believe in this nonsense.

Nic Williams

Scratch the surface and gender identity politics crumbles to dust. We know this and so do transgender ideologues. Their only option is to attack the whistle-blowers, they have no other cards to play. But shaming us into silence or bullying us into submission can only work for so long. Attempts to discredit the women that do speak out eventually fail. There are simply too many of us to keep the lie going forever. And once out the truth only moves in one direction. I decided to speak up 2 years ago. This was because I could and because of the courage and actions of others who spoke up before me. My own courage and actions can now persuade and inspire others to speak up, and so it goes on. We all have our role to play, some of us will speak to thousands from from a stage and some of us will drop it into conversation with a friend, colleague or stranger. It all counts. Every time we feel the fear and do it anyway, we are doing our bit for women and the girls who follow behind us. You never know who that message will reach or who you will have inspired.

Kiri Tunks

There’s no question that I’ve been attacked for speaking up. I had naively assumed that my long record of fighting for equality would mean I was shown a bit of respect but I soon realised that this record counted for nothing. I have been publicly vilified and smeared (including by some people I thought were comrades and friends). I have been the subject of two petitions to have me removed from national roles in my union; there have been attempts to ‘blacklist’ me from campaigns I’ve been involved with for years; I’ve been disinvited from meetings and events. All for campaigning for women’s rights – as I have always done. Luckily, many others have been more principled in their solidarity and support. Some who started off disagreeing with me did take the time to talk to me and now understand my position. Some have changed their minds. Speaking up in the face of such hostility can be hard but it is liberating. I have never regretted the stand I have taken. I have met amazing women who have enriched my life and work. And I feel stronger than ever.

Stephanie-Davies-Arai

It might seem hard to speak out when you see how women are vilified, bullied and silenced even for talking about basic biology. Being called a bigot and experiencing relentless harassment is one thing, the real risk of losing your job is quite another and there are many brave women working hard behind the scenes who can’t risk that. I am in a position where I can speak out and so I do. When it gets overwhelming I remind myself that I would feel so much worse if I could see what was happening but did nothing about it.

Julia Long

The attempts to silence us are vicious and relentless. Trans activists tried to sabotage a conference I was coordinating back in 2012, and I was called to three meetings with senior management when I was working in academia, due to external complaints. The university was always very supportive. I was also the subject of a grievance complaint in another job, for my supposed ‘transphobia’. The grievance was not upheld. Just this year, I was physically removed from an event where I was sitting perfectly peaceably by two male security staff and seven police officers, and back in July I was part of the group that was refused service and instructed to leave a bar of the National Theatre. For me, speaking the truth is vital and I have prioritised this in my life. I am very fortunate in not having dependents or being reliant on a job that is conditional upon my silence. But of course many women are in very precarious positions, and each woman must decide for herself how, when and if she wishes to speak out. And I totally respect that. What frustrates me is when those groups and individuals who act as spokeswomen or assume positions of leadership refuse to speak the truth and seek to marginalise those of us who do. There is a lot of that in the ‘gender critical’ movement, mainly due to the baffling refusal to straightforwardly name men as men.

Michele Moore

I am not brave but the stories of families, detransitioners and trans people themselves from all ovef the world who are worried about the lack of evidence for safe transition of children and young people has driven me on. People are open mouthed when they understand the difficulties I’ve been undergoing are based on false accusations and malicious communications. The threats I and others have endured need time to process and heighten our sense of respect for those who are willing to speak out. When people say they admire my work I can fight another day to keep children and young people from the harm of identity politics.

Helen Watts

I spoke up because I believe in leading by example. I couldn’t encourage girls in my care to find their voices if I wasn’t prepared to use mine to protect their interests. No one should be treated unfairly – trans or not – and it was the blatant unfairness of the Guides’ policy that meant I could no longer be silent. I’ve stayed neutral on the anonymity debate. It was a matter of honour for me to use my real name but I acknowledge that my particular circumstances allowed me to be so open. Many women do not have that luxury. Speaking up isn’t about twitter followers or press articles; raising the issue privately, in 1:1 conversations with friends and family, or supporting women’s causes is just as- if not more- important. Every action, no matter how big or small, counts.

Kathleen Stock

I think that for me, its important that all women (and male allies) think strategically about how they can best contribute to the fight. That might be to speak out in public under your own name, but equally that might not be a strategically sensible move, if that means losing your main source of income without hope of another. Your poverty won’t help. The right thing might instead look like having brave, respectful, face-to-face conversations with work colleagues, friends, and family; or seeing your MP. Strategic thinking also involves considering whether shouting at someone under a pseudonym on Twitter or Facebook is doing anything positive to advance the movement.

And finally….

This month we said farewell to the brilliant, irreverent and irrepressible Magdalen Berns.

I massively admired Magdalen. I can’t ask her for a quote, of course, because she is gone.

I admired her no nonsense approach, her committal to the truth and her blunt belief in telling men ‘you’re not a woman‘. Magdalen was the first person I heard use the phrase ‘there’s no such thing as a lesbian with a penis.‘

In what sort of world do those become controversial statements?

I met Magdalen just twice and we chatted a bit, about nothing in particular. On one occasion, as a group of us walked from Westminster to a bar, I offered her a piggyback and she said something sarcastic. She was tiny with a huge personality; articulate and incredibly funny.

Watching Magdalen’s videos is an education in itself. She certainly wasn’t afraid to speak out and encouraged others to do so, towards the end of her life urging others to ‘be brave‘.

‘Because, as I’ve always said, there’s a lot more to worry about than being called silly names.’

You can read obituaries for Magdalen here, here and here.

“So what can I do?”

Some of us are stronger than others, some of us are in a better position to speak out, some of us have more privilege or less of a filter. There may be limits to what you feel you can do and that’s ok, but once you understand what’s going on in the world of identity politics you will probably feel obliged to do something. You may already be doing your best, in which case well done, keep on doing it. I’m not trying to tell anybody else what they should do, but here are a few ideas.

Stealth activism

We need to make a difference where we can. If you don’t feel you can hand out leaflets in your hometown or start a YouTube channel, maybe you can leave stickers lying around, or slip postcards into books in libraries and bookshops.

If you have a printer, it’s easy to make your own postcards or stickers. Or you can get a site like Moo to print your own designs. Leaving a postcard in a bookshop isn’t comparable to one of Posie’s epic billboards, but it may make ripples. It all counts.

Attend meetings. Watch some YouTube videos. There’s lot of good gender-critical stuff on YouTube, although you may need to dig a bit. Read and read some more. My friend Lesley swears by gender critical Reddit. There’s some good stuff on Mumsnet. Follow some of the people above or join facebook groups (remember many aren’t secure) to find out what’s going on in your area. If you don’t feel you can protest on marches, maybe you can write to your MP. Anyone can fill in a consultation or a survey. If you don’t feel you can write to your child’s school, maybe you can still cross out ‘gender’ on a form and write in ‘sex’.

Check out the Transgender Trend website. Afterwards, you may want to write to your kids’ schools and clubs after all, referring them to the Transgender Trend schools resource packs.

Prepare yourself for conversation.

At your child’s gymnastics competition, someone expresses support for girls in sport. Ask them casually what they think about boys taking places on girls’ teams and winning. Read Dr Emma Hilton’s speech here so you have facts at your fingertips if the conversation takes off. Check out the Fair Play for Women website for loads of information about men in women’s sports.

In response to ‘transwomen are women‘ you can raise the subject of rapists in women’s prisons, penises in women’s refuges. Most people don’t know that 70%+ of transwomen keep their penis. Having concerns about this doesn’t mean you think all trans people are sex offenders any more than being concerned about rape means you think all men are rapists!

If LGBTQ+ rights are discussed, find out what people think about lesbians with penises. Tell them about the cotton ceiling. Ask them what they think the word lesbian means when lesbians are expected to embrace penises. Is this fair on lesbians? Ask them what ‘same-sex attracted’ means if transwomen are really women. Should gay men be expected to have sex with transmen? Is it transphobic if they don’t want to? These are important questions.

You don’t have to jump up on a table and bang a drum. All these things can be asked with calm curiosity and expressed as a desire to be educated.

If the subject of trans children is raised, you can ask what people think about 14 year old girls having their breasts removed in Canada. If someone says surgery doesn’t happen to British kids, you can mention what happened to CEO of Mermaids Susie Green’s child. If they say kids can’t get hormones easily, mention Helen Webberley prescribing them to 12 year olds. If we didn’t have sexist stereotypes, how could a child be trans? What about the psychological effects of social transition on a child? What about the right of girls to have bodily privacy when changing or using toilets at school?

I was being tactless when I blurted out ‘Non-binary is bollocks’ to a teacher in a London college last month (for clarity we were not in a class at the time). It was not tactful but it was true, and yes, it was just a little bit brave. I’ve let a little time pass: next week I’m going to email her some articles backing up what I said.

Rebecca Reilly-Cooper’s article ‘Gender is not a Spectrum‘ is a great article for emailing friends who are starting to question.

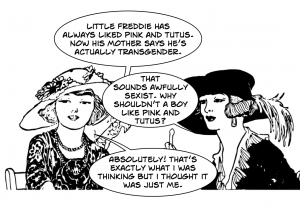

Commenting, ‘gosh, isn’t that awfully sexist?’ when someone tells you her friend’s sister’s husband says he has ‘always felt he’s a woman‘ isn’t going to change the world, but it might help your friend consider the issue a little more deeply.

Commenting, ‘gosh, isn’t that awfully sexist?’ when someone tells you her friend’s sister’s husband says he has ‘always felt he’s a woman‘ isn’t going to change the world, but it might help your friend consider the issue a little more deeply.

If we don’t communicate, how do we expect others to know what we’re thinking? If we don’t communicate, how do we expect to challenge our own ideas and those of others?

I’m hoping to speak at a public event later this year. Openly.

Maybe we can all try to be a little bit braver.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

– Margaret Mead

“amazing…

“amazing…

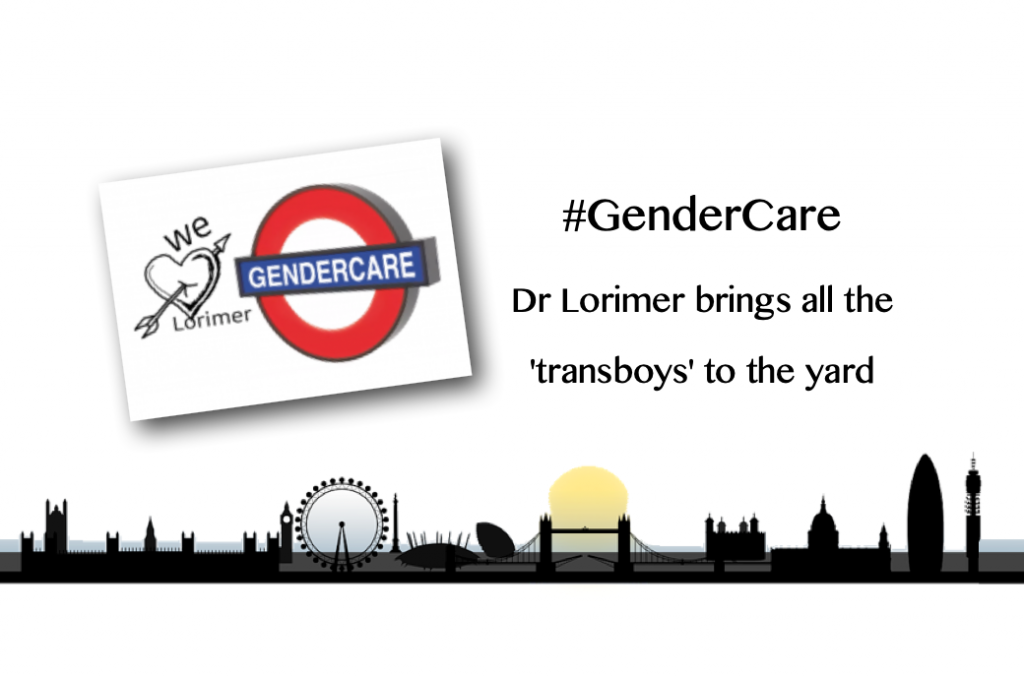

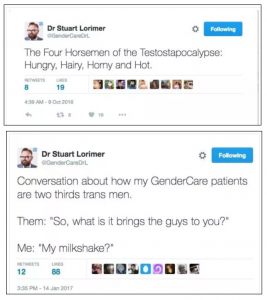

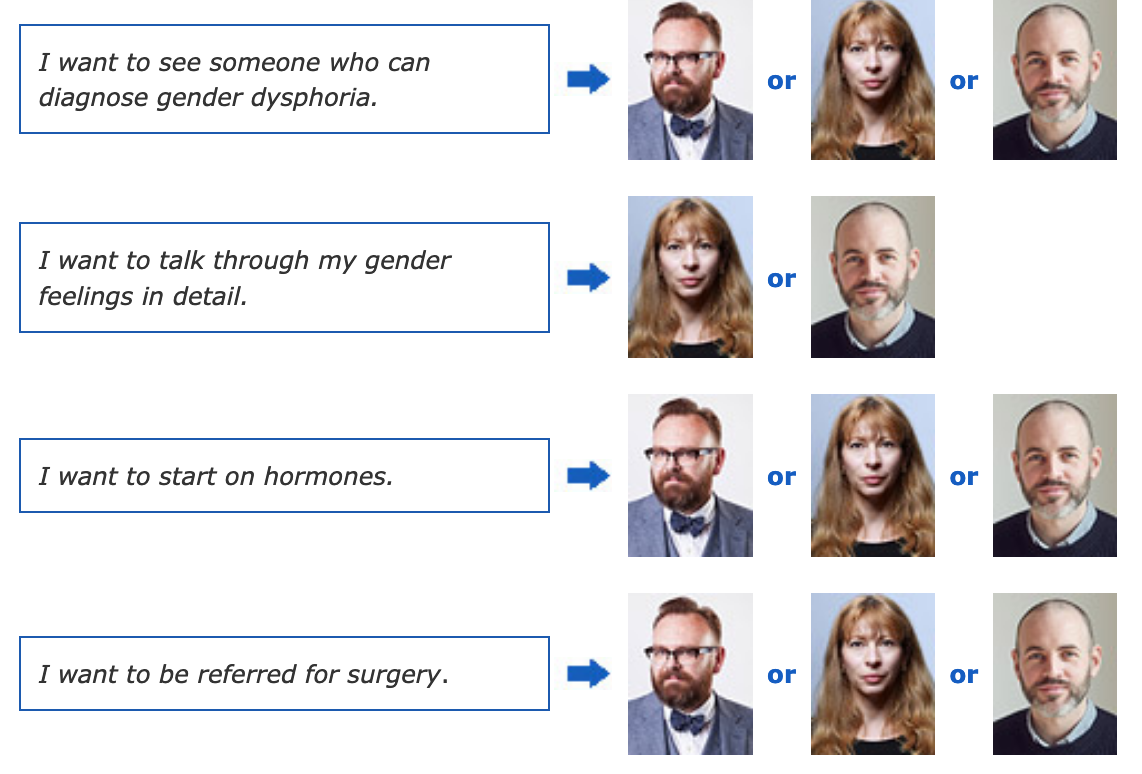

GenderCare only deals with adults- although the young women in the videos I watched all looked astonishingly young. Lorimer admits to having had at least one patient as young as seventeen, tweeting in 2017: ‘My youngest patient is 17, my oldest 96’.

GenderCare only deals with adults- although the young women in the videos I watched all looked astonishingly young. Lorimer admits to having had at least one patient as young as seventeen, tweeting in 2017: ‘My youngest patient is 17, my oldest 96’.

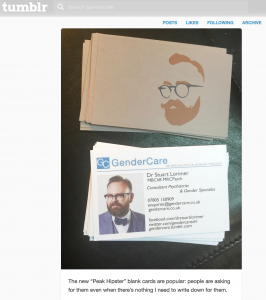

In 2016 Lorimer arrived on Tumblr, an area of the net frequented primarily by teenagers. ‘Tumblr, like lycra is probably not for anyone over 30 –yet here I am’ announced Lorimer chirpily, posting his trendy business cards while making it clear that he didn’t represent his ‘NHS employers or my GenderCare colleagues’. Oh and adding that he may post pictures of cute animals.

In 2016 Lorimer arrived on Tumblr, an area of the net frequented primarily by teenagers. ‘Tumblr, like lycra is probably not for anyone over 30 –yet here I am’ announced Lorimer chirpily, posting his trendy business cards while making it clear that he didn’t represent his ‘NHS employers or my GenderCare colleagues’. Oh and adding that he may post pictures of cute animals.

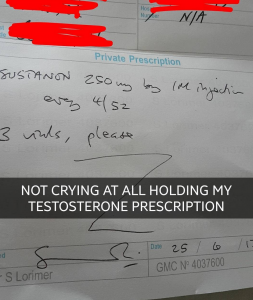

Instagram posts with the hashtag #gendercare often contain pictures like this one, a prescription for testosterone prescribed by Lorimer, accompanied by cheers of ‘well done bro’ and ‘yay congrats’ in the comments.

Instagram posts with the hashtag #gendercare often contain pictures like this one, a prescription for testosterone prescribed by Lorimer, accompanied by cheers of ‘well done bro’ and ‘yay congrats’ in the comments. Another photo of a prescription is accompanied by the words “I filed this prescription today. So surreal. Its finally happening. ?’ #gendercare

Another photo of a prescription is accompanied by the words “I filed this prescription today. So surreal. Its finally happening. ?’ #gendercare “It’s not an adventure if you know what is going to happen” posts one young client after a ‘gofundme’ paid for her appointment with GenderCare.

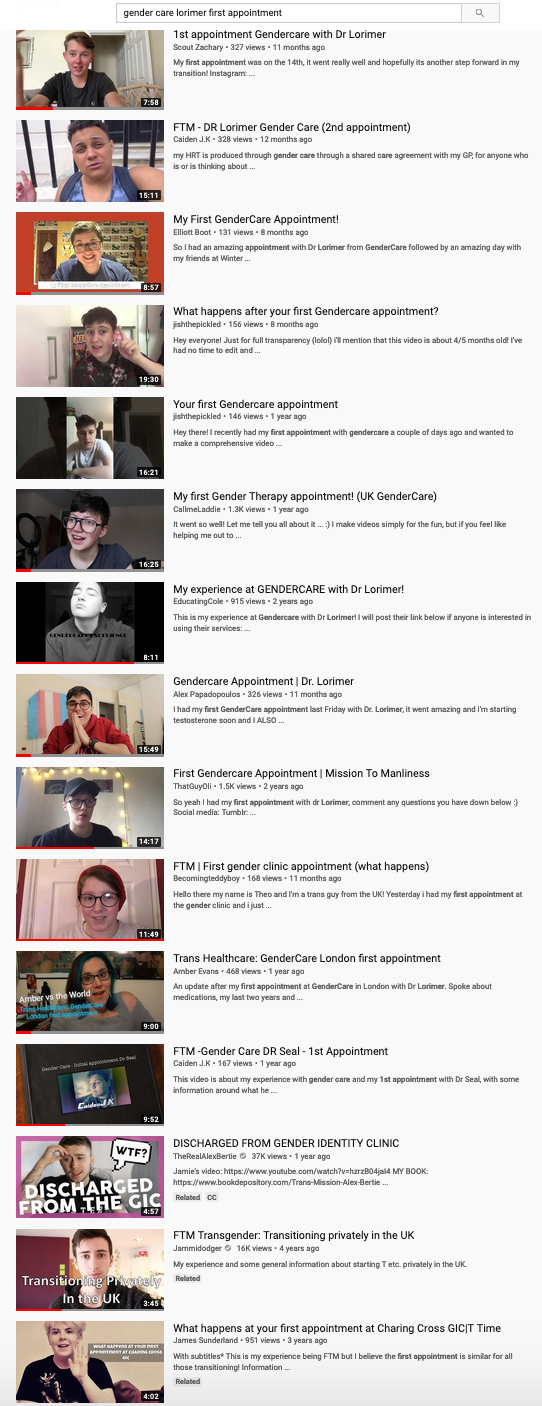

“It’s not an adventure if you know what is going to happen” posts one young client after a ‘gofundme’ paid for her appointment with GenderCare. Don’t take my word for this. You too can while away several never-to-be-regained hours of your short life by watching these diverse yet strangely homogeneous young women talk about their experiences with GenderCare. They have put their experiences on YouTube; they want their transition videos to be seen. Views are important.

Don’t take my word for this. You too can while away several never-to-be-regained hours of your short life by watching these diverse yet strangely homogeneous young women talk about their experiences with GenderCare. They have put their experiences on YouTube; they want their transition videos to be seen. Views are important.  Suddenly a generation of young women (and men, but this article is focused on the women) have been told this is a reasonable thing to believe.

Suddenly a generation of young women (and men, but this article is focused on the women) have been told this is a reasonable thing to believe.