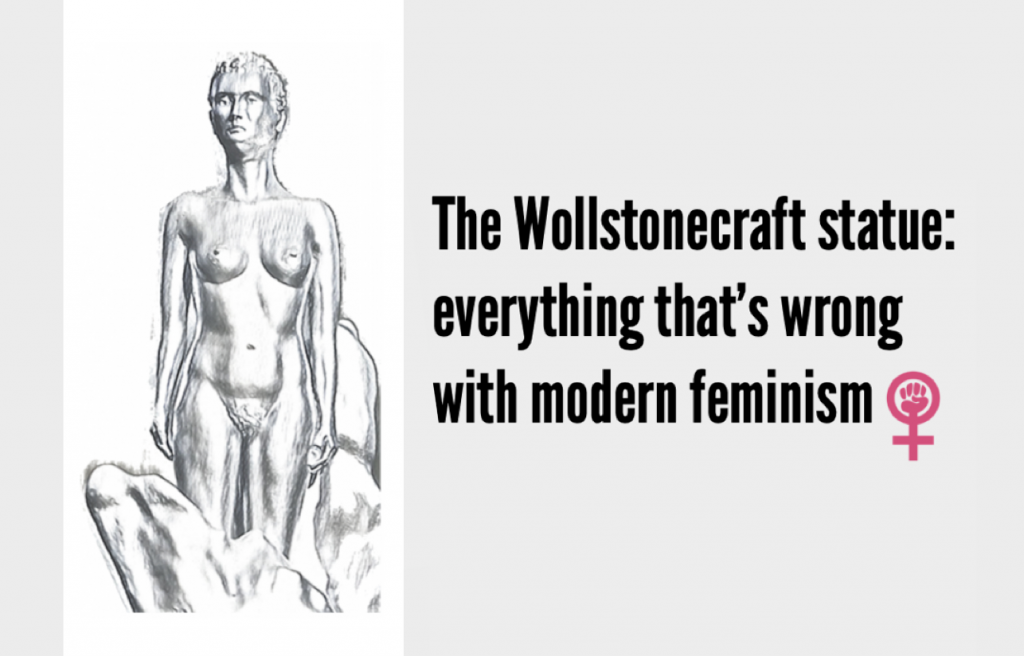

This week a new statue was unveiled on North London’s Newington Green. The £143,300 sculpture is for eighteenth century feminist and author Mary Wollstonecraft.

“Great! Just what we need! A statue of an inspiring woman.” I hear you cry. Well, yes. And also no. Curb your joy for a moment. The statue, as you probably are aware, has sparked controversy.

Statues of Women? Where?

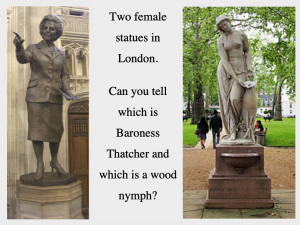

There’s no doubt that there’s a lack of statues of women in London. Not nymphs or nudes, not random languishing females- although to be fair even those are far and few between- but statues to actual, real women, who once lived and breathed and Did Things.

The ‘Statues for Equality‘ website tells us that women make up just 6.5% of the 265 statues in London depicting historical figures. That’s still double the percentage in the UK overall, where representations of women (excluding the mythical and the royal) make up just 3% of statues.

“(There are) 25 statues of historical, non-royal women (in the UK), one of whom is a ghost and only there because she’s looking for the spirit of her murdered husband. Meanwhile, there are 43 statues of men called John.” reported Caroline Creado-Perez in 2016.

The BBC’s ‘Reality Check: How many UK statues are of women?‘ points out that statues of females are more likely to be nameless and/or linked to myth or allegory. Many of these nameless females are nymphs and nudes whereas nameless statues of men are more likely to be soldiers.

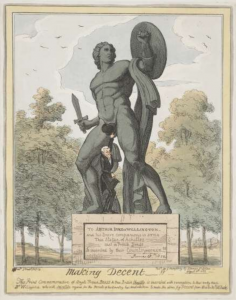

Wilberforce attempts to cover Achilles’ knob with his hat

“We don’t put up commemorative nude statues in tribute to men, do we?” I complained to Susan Matthews. “That would be ridiculous.”

“Well, we did, actually,” she replied. “The first public nude statue in modern times in the UK was the Achilles statue to Wellington which was paid for by a female-only subscription. Wilberforce was outraged. Here’s the Cruickshank caricature.”

The Achilles statue was installed by order of King George III and unveiled on 18 June 1822. The head of the statue was based on that of the Duke. Following public outrage, a fig leaf was added to cover the blushing hero’s genitalia.

This is not entirely the same, of course. Achilles, like Wellington, was know for his efforts in the art of war. The ‘mars aspect’ of manliness, if you will. Wollstonecraft is know for her serious political activism. Would we see – as posited by Linda from Kent during the debate on The Jeremy Vine show – a naked statue put up to Nelson Mandela or Winston Churchill? Of course not.

But I digress. Back to statues of women.

Queen Victoria wipes the board with the rest; we have an astonishing 29 statues of her. Unsurprisingly, none are nude.

Queen Victoria wipes the board with the rest; we have an astonishing 29 statues of her. Unsurprisingly, none are nude.

In 2018, 65 statues of male politicians were recorded by the PMSA as inhabiting public spaces around the UK. How many statues of female politicians do we have? They recorded none, although there is a statue of Margaret Thatcher on view to members of the public in the House of Commons.

According to Statues for Equality there were eleven statues of named women (excepting myths and royalty) standing in public spaces in London in 2018. I list them here in order of the year they were unveiled:

Welsh-born actress Sarah Siddons (1897), feminist and social reformer Margaret Ethel MacDonald (1914), nurse and writer Florence Nightingale (1915), nurse & resistance member Edith Cavell (1920), Salvation Army co-founder and christian feminist Catherine Booth (1929), writer Virginia Woolf (2004), secret agent Violette Szabo (2009) radio operator, spy and Indian princess Noor Inayat Khan (2012), British-Jamaican nurse and businesswoman Mary Seacole (2014), theatre director Joan Littlewood (2015), feminist & union leader Millicent Fawcett (2018).

Clearly there is an imbalance of the sexes here which needs redressing.

Which brings us to ‘Mary on the Green’.

Planning for the Mary Wollstonecraft Memorial Statue

The organisation ‘Mary on the Green‘ (MOTG) came up with a plan consisting of two aims. The first was to establish a memorial, ‘a symbol of her (Wollstonecraft’s) legacy in a public statue/work of art’, near the site of the school Wollstonecraft founded with her sister and best friend. The second was to establish The Wollstonecraft Society: ‘a network of people, a promotion of ideas and an outreach programme of accessible learning materials’.

“Why should Mary Wollstonecraft have a statue?” asks MOTG. “Because our statues send a powerful message about what matters to us – and implicitly about what doesn’t.”

‘The memorial will be a tangible way to share Wollstonecraft’s vision and ideas. Her presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people in Islington, Haringey and Hackney… and it will send a powerful message beyond that, across the world. Just as the image of Churchill’s memorial statue is used in debates on his legacy, the same is needed for Mary Wollstonecraft.”

So this all sounds pretty hopeful, right? A statue of Mary Wollstonecraft: know to many as the mother of feminism, actual mother of Mary Shelley and writer of ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman‘. You don’t have a copy? Nor do I; if you’re feeling inspired you can read it online here.

Before we go any further, let’s have a look at the life and works of Mary Wollstonecraft. She seems to have been a fascinating and hugely intelligent woman, full of compassion, complexities and contradictions. I spent several days reading through online biographies and collected some of the most interesting bits to share with you here.

Mary Wollstonecraft

A short biography

“Her person was above the middle height, and well proportioned; her form full; her hair and eyes brown; her features pleasing; her countenance changing and impressive; her voice soft, and, though without great compass, capable of modulation. When unbending in familiar and confidential conversation, her manners had a charm that subdued the heart.” Mary Hays (1797)

Mary was born in London in 1759, the second of seven children. Only her brother Edward, ‘Ned’, received a formal education. Her Irish mother, Elizabeth, described as ‘weak but harsh’ favoured her eldest son over Mary. Her father Edward John, who inherited some property from his own father, was a violent alcoholic and Mary frequently tried to protect her mother from his rages. Mary left the family home aged 19 to become a lady’s companion in Bath, where she missed her best friend, artist Fanny Blood. Mary returned home to nurse her mother, who died in 1781. After her mother’s death she moved in with artist Fanny and her family. The young women predicted happier times in the near future, planning to rent rooms together and support each other. The depth of their passion for each other was such that many speculate on a love affair. Who knows?

Fanny Blood

“Romances between women with no implication of a sexual bond, were common in Wollstonecraft’s day,” writes Barbra Taylor in ‘Mary Wollstonecraft and the feminist Imagination’.

“Nonetheless the ferocity of Wollstonecraft’s feelings for Fanny (so powerful according to Godwin as ‘for years to have constituted the ruling pattern of her mind’) at least raises the possibility of a homosexual attachment.”

In 1784 Mary proved herself both headstrong and compassionate when she assisted her sister Eliza, newly-wed and unhappy, to escape her husband and leave behind her infant daughter. The same year Mary, Eliza and Fanny established a school together, in Newington Green. Fanny married fairly suddenly and somewhat unenthusiastically, moving to Portugal with her husband. When Fanny became seriously ill in pregnancy, Mary left the school and followed to Portugal to help care for her. We are told that Fanny died ‘in Mary’s arms’, and her baby died shortly afterwards.

The school had floundered and failed in her absence and a devastated Mary fled to Ireland where she took work as a governess under the formidable Lady Kingsborough. It was here, while fighting depression, that she completed her first novel.

‘Mary: a fiction’ (which I have only partly read) has strong autobiographical elements and some have interpreted it as a tale of doomed lesbian love. Thanks to the Gutenberg project, you can read it here.

On her return to London Mary published her first book, ‘Thoughts on the Education of Daughters’ in 1787. She began working as an editor and translator for her publisher Joseph Johnson. Remember, Mary had not been sent to school, she had had no governess, neither of her parents were intellectuals and she had not- beyond a short time in Portugal- been abroad. Yet she had educated herself to the extent that she was able to work translating complex theoretical texts from Dutch, German and French into English.

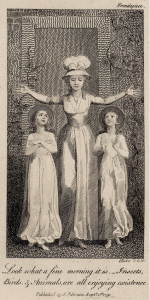

frontpiece for Original Stories, by William Blake

“To understand the extent to which Wollstonecraft made up for the lack of a formal education, it is essential to appreciate fully that her talents were to extend to translating and reviewing,” writes Tomaselli in the Stanford Encycolpedia of Philosophy. “In each case, the texts she produced were almost as if her own, not just because she was in agreement with their original authors, but because she more or less re-wrote them.”

During this time Wollstonecraft wrote her only children’s book, Original Stories from Real Life (1788) which was illustrated by poet and artist William Blake.

She was also a regular contributor to Johnson’s Analytical Review. In 1790 she published, initially anonymously, A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke.

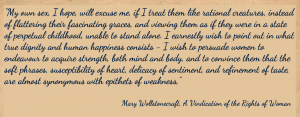

Mary is, of course, most famous for her work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which made the revolutionary call for women and men to receive an equal education. You can read it here.

“Confined then in cages, like the feathered race, they have nothing to do but to plume themselves, and stalk with mock-majesty from perch to perch.”

Wollstonecraft advocated for an egalitarian education system which would result in women being not only excellent wives and mothers, but capable professionals and competent thinkers. Her religion was at the centre of both her feminism and her views on education. She believed that the soul is not sexed and that, without the means to develop their capacity for reason, women are incomplete.

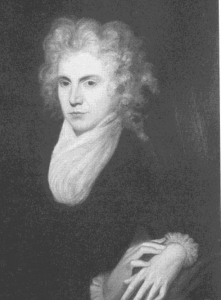

Mary Wollstonecraft 1791-2 – artist unknown

In 1792 Wollstonecraft moved to Paris, to view the French revolution close at hand and ostensibly to escape a doomed romance with brooding, bisexual, supernatural painter Henry Fuseli, whose wife was none to keen on Mary’s idea of the three of them living together in a menage à trois.

Arriving in Paris in time for the trial of Louis XVI, Mary was surprised to find herself moved to tears by the sight of him on his way to inevitable death. She had planned to stay only a few weeks but remained in France for two years. In Paris she fell in love with and lived with ‘Captain’ Gilbert Imlay, a timber merchant, businessman and writer. After the decree that all British nationals should be imprisoned until after the war, Imlay registered Mary as his wife at the American embassy. Mary wrote to her friend Ruth Barlow:

“‘You perceive that I am acquiring the matrimonial phraseology without having clogged my soul by promising obedience &c &c.”

Mary lost several friends to the guillotine, ran close to being imprisoned herself, quickly became pregnant by Imlay and gave birth to a daughter, Fanny. In 1794 she wrote a history of the early revolution, An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution. Imlay had promised her they would move to America together once he had saved £1,000 from his business but eventually he abandoned her and their child in France. The Seine river froze that winter. Food and coal were scarce in Paris and many starved or froze to death. Eventually Mary and baby Fanny returned to London where Mary made two suicide attempts. After the first she travelled to Scandanavia on business for Imlay, still hoping for reconciliation, and of this time she wrote “Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796). Her second suicide attempt was to jump, soaked from the rain, into the Thames, but she was saved by a passer by. She had left a note for Imlay concluding, “May you never know by experience what you have made me endure.”

Slowly, she returned to work in publishing, mingling with the like of actress Sara Siddons and novelist Elizabeth Inchbald. It was here that she met and married William Godwin, giving birth to her second daughter a few months after their wedding. Less than a fortnight after the birth of baby Mary (who would grow up to write ‘Frankenstein‘) Mary Wollstonecraft died of puerperal fever, brought on by a non-sterile internal exam by a male doctor, during childbirth.

Shortly after her death, her unfinished novel Maria; or, The Wrongs of Woman was published. Maria is shut up in a madhouse by a husband who wants control of her fortune. Described as ‘a novelistic sequel’ to A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, it is said that the faithless Imlay is represented in the novel by an “an engaging though not very intelligent lover”.

After her death, Godwin worked through his grief by writing and published a candid memoir of her life.

“True to his philosophical belief in absolute sincerity, Godwin coolly describes Wollstonecraft’s previous love affairs, her time in revolutionary Paris, her illegitimate child, and her two suicide attempts. The book almost wrecked both their reputations, but can now be seen as a masterpiece of indiscretion and human honesty.” Harper Collins

“As a result her demand for rational female education, which had been accepted by most thinking women, became almost forgotten in the light of her implied demand for sexual freedom.” wrote Janet Todd in 2017. “She was hugely reviled as a ‘prostitute’ and ‘unsex’d female’. Few of the later feminists of the more conservative 19th century would dare to admit her influence openly, as they made their gains for women by limiting the feminist agenda.”

“What has exercised her critics most is the gulf between her pioneering public persona, with its strident appeals for the independence of women… and her pathetic, private dependence on a series of incorrigible cads.” wrote Kelly Grovier in 2005.

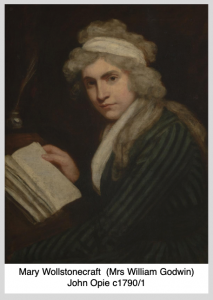

John Opie’s painting of Wollstonecraft (circa 1791) is housed in the Tate Gallery, London. The painting bears this display caption:

John Opie’s painting of Wollstonecraft (circa 1791) is housed in the Tate Gallery, London. The painting bears this display caption:

Wollstonecraft was a ground-breaking feminist. This portrait shows her looking directly towards us, temporarily distracted from her studies. Such a pose would more typically be used for a male sitter. Women would normally be presented as more passive, often gazing away from the viewer.

How far have we actually come? Some might argue that Opie’s 300 year old depiction of Wollstonecraft was more liberal, more progressive, more forward-thinking than that of the artist chosen to represent her 300 years later.

Which brings us to – the Shortlist and the Statue

A competition was held to decide who would receive the commission for the memorial statue. Two designs were shortlisted, works by artists Maggi Hambling and Martin Jennings.

If you live or work in London you may well have seen Martin’s work. That larger-than-life George Orwell outside Broadcasting House? Or- if you can afford the vast admission fee- his sculpture of the Queen Mother sits inside St Paul’s Cathedral.

Jennings’ powerful statue of Mary Seacole stands outside St Thomas’s Hospital in London. Against a disc cast from shell-blasted Crimean rock, she has been described as “striding purposefully towards the Houses of Parliament across the river, cape billowing behind”.

My personal London favourite is his Sir John Betjeman (2007) on St Pancras Station. Betjeman seems so endearing: a little bumbling, lost and bemused at the world changing around him, hanging on to his bag of books.

Among his many other works, Jennings is creator of ‘Women of Steel’. The Sheffield statue features two women, a welder and a riveter, linking arms. They are ‘the women who started out young and inexperienced but by the end … were the equal of the men who returned from war to reclaim their jobs’.

Tourists, locals and politicians link arms with the statues for photo ops and the statue is now considered to be a ‘popular focus of Sheffield’s pride in its women’s history’.

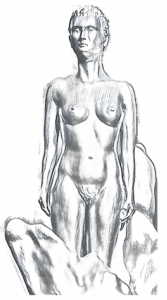

Jennings’ proposal for the Mary on the Green sculpture.

“I have proposed a statue of her that expresses her heroic courage and her sheer force of personality,” proclaimed Jennings, and suggested this design (right). The statue, cast in bronze and set in stone, would have seating on either side, “to stand in place for at least as many centuries as her reputation has been neglected.”

“I have proposed a statue of her that expresses her heroic courage and her sheer force of personality,” proclaimed Jennings, and suggested this design (right). The statue, cast in bronze and set in stone, would have seating on either side, “to stand in place for at least as many centuries as her reputation has been neglected.”

Maggi Hambling

Likewise, if you live or work in London you may well have seen Hambling’s work. Her statue ‘A Conversation with Oscar Wilde’ has stood on Adelaide Street opposite Charring Cross station since 1998.

Likewise, if you live or work in London you may well have seen Hambling’s work. Her statue ‘A Conversation with Oscar Wilde’ has stood on Adelaide Street opposite Charring Cross station since 1998.

I have always rather liked it. Is it a bench? Is it a statue? Is it a coffin? Oscar’s face leaves me both attracted and repelled, much as I imagine I would have felt in the presence of the man himself. Enscribed on the front is Lord Darlington’s famous line from Lady Winderemere’s Fan, ‘We are all in the gutter but some of us are looking at the stars’. Often, empty cans of Special Brew and cigarette butts lie like forlorn offerings at its feet.

“The idea is that he is rising, talking, laughing, smoking from this sarcophagus,” said Hambling. “It is actually completed when a member of the public sits down and has a conversation with him.”

The sculpture caused some controversy. It was featured in the 2015 Guardian article ‘The scourge of the bronze zombies: how terrible statues are ruining art‘. Art critic Tom Lubbock called it an ‘anodyne figment.. a macaroni tangle”, but many people seemed to like it. The Londonist featured it in ‘London’s Best Literary Statues’.

Hambling is also known for her ‘Scallop’, a tribute to Benjamin Britten. Located on Aldeburgh beach since 2003, described as an ‘iconic image of the Suffolk coast‘, ‘Scallop’ is a six and a half ton, fifteen feet high stainless steel shell bearing the quote, ‘I hear those voices that will not be drowned’.

Hambling is also known for her ‘Scallop’, a tribute to Benjamin Britten. Located on Aldeburgh beach since 2003, described as an ‘iconic image of the Suffolk coast‘, ‘Scallop’ is a six and a half ton, fifteen feet high stainless steel shell bearing the quote, ‘I hear those voices that will not be drowned’.

“Children love it. Lovers love it. Those paying tribute to lost loved ones gather around it. And there are those who would wish it melted down or carted away.”

Decisions, decisions

“These are the two shortlisted designs showing how the long-awaited statue of revolutionary 18th century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft on Newington Green could look.“ reported the Islington Tribune in March 2018.

“These are the two shortlisted designs showing how the long-awaited statue of revolutionary 18th century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft on Newington Green could look.“ reported the Islington Tribune in March 2018.

In May 2018 it was revealed that Maggi’s design (left) had been accepted and Jennings’ idea was to be shelved.

Two questions spring to mind. Why was a statue chosen that wasn’t a depiction of Wollstonecraft? What message exactly do we think the chosen statue sends to women and girls the world over?

“This is a radical proposal embodying radical ideas.” said MOTG patron Jude Kelly. “The figure, an everywoman, emerges out of organic matter, almost like a birth. This evokes Newington Green as the birthplace of feminism, and echoes Wollstonecraft’s claim to be “the first of a new genus.”

“I hope the piece will act as a metaphor for the challenges women continue to face as we confront the world.” said Hambling, accepting the commission.

Anne Birch, spokeswoman for the campaign said, “We have gone for something metaphorical rather than a sculpture or portrait of her because we wanted to celebrate her spirit. We’re not walking in the footsteps of the bronze male sculptures and what they do in Parliament Square. We wanted to do something different that will really attract passersby to look at it.”

Why was Hamling’s work chosen over Jennings? Well, possibly, partly, maybe, Jennings’ idea may have been rejected because of his sex. Of course it would be preferable to have a statue to a feminist icon that was actually designed by a woman.

It’s important to remember that there was a public consultation held, and Hambling was selected unanimously by a judging panel consisting both of members of the public and of professional curators.

Whilst some might say that both ‘Mary on the Green’ and the artist have been clear that the statue is not of Mary Wollstonecraft but for her, contributors to the collection could have been forgiven for having assumed it would be the former. For example, the website mentions how inspiring MW’s ‘presence in a physical form’ will be.

Whilst some might say that both ‘Mary on the Green’ and the artist have been clear that the statue is not of Mary Wollstonecraft but for her, contributors to the collection could have been forgiven for having assumed it would be the former. For example, the website mentions how inspiring MW’s ‘presence in a physical form’ will be.

“It’s time we celebrated the women who have shaped our country.” tweeted supporter Tom Watson in March 2019. “Let’s start with a statue of Mary Wollstonecraft – one of the great pioneers of women’s equality.”

Not a lot of objections seem to have been raised when the decision to commission Hambling’s piece was announced over two years ago.

And then, in November 2020, the £143,300 statue was unveiled.

You can view the Mary on the Green video of the installation and unveiling here.

“My sculpture involves this tower of intermingling female forms, culminating in the figure of the woman at the top, who is challenging and ready to challenge the world,” said Hambling. “My statue is silver because I feel silver to be a much more female colour than bronze. The silver will catch the light and float in space.”

Bee Rowlatt, chairwoman of the MOTG campaign for a statue, told the BBC: “Her ideas changed the world. It took courage to fight for human rights and education for all. But following her early death in childbirth, her legacy was buried, in a sustained misogynistic attack. Today we are finally putting this injustice to rights. Mary Wollstonecraft was a rebel and a pioneer, and she deserves a pioneering work of art.”

You have almost certainly already seen a picture of the installed statue. Before you look on it again, reflect on the short but event-packed life of this woman, her formidable intellect and thirst for knowledge, her impassioned dedication to the women and men that she loved, and her commitment to feminism and equality through education. Consider this quote from The Vindication of the Rights of Woman:

“Taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.“

Dwell again on the original vision dreamed by MOTG, of a statue that would be ‘a tangible way to share Wollstonecraft’s vision and ideas.’

A statue with as much artistic grace and power as that of Churchill; a statue whose ‘presence in a physical form’ would be an ‘inspiration to local young people’.

And what did we get?

We got this.

And we were not impressed.

To be fair, some people were. “I want to be friends with her and I want to be like her.” wrote Olivia Alabaster in the Independent.

By ‘be like her’ I can only presume Olivia doesn’t mean naked in the middle of Newington Green.

“The tiny proportions of the naked female figure that tops it bring to mind a 1970s Pippa doll, a toy that, even as a child, I identified as utterly pathetic.” mused Rachel Cooke in the Guardian.

“Currently a lot of people are rightly wondering why a woman who fought to be recognised for her brilliance and yet was shamed for her free spirit and liberated views on sexual freedom is being celebrated with a nude.” wrote Robert Dex in the Standard.

“It’s not making me angry in any way,” tweeted Caitlin Moran, “because I just KNOW the streets will soon be full of statues depicting John Locke’s shiny testicles, Nelson Mandela’s proud penis, and Descartes adorable arse.”

Imogen Hermes Gower tweeted, “Nameless, nude and conventionally attractive is the only way women have ever been acceptable in public sculpture. This was a chance to break from those conventions, no?””

Pam Ayres even wrote a poem for the occasion:

“Poor Mary Wollstonecraft

Bare-bottomed fore and aft

Would she not prefer to be

Left in her obscurity.”

@janeanne_marie responded with:

“I don’t like this nudist racket

I will knit her a little jacket.”

And indeed somebody, quite possibly Jane, did knit her a cover-up, leaving a little knitted tanktop beside the statue with the message “Hey Everywoman. Put on a vest and find some strong boots. There’s work to be done.”

Journalist Katherine Faulkner posted on Twitter that she had met two members of the committee when she visited the statue. She believes she received some insight into why Hambling’s design was chosen.

“They were lovely and well meaning. You could see on their faces that they knew it looked awful, and that a terrible mistake had been made. When I asked why they voted for this design over the other, they looked embarrassed and said that said that it was felt the other statue – which showed Mary Wollstonecraft clothed, with a stack of books, was too ‘prosaic.’ They also thought people would criticise them for choosing the male sculptor over the female. So in other words, out of an intellectually muddled notion of equality, the committee chose the woman sculptor at all costs – regardless of the merits of the design.”

Bee Rowlatt of ‘Mary on the Green’ defended the artist and the decision. “It’s categorically not a statue of Mary Wollstonecraft. Maggie Hambling has been very clear on that… she has created a sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft, so that naked body is not MWs body!”

But is that even the point?

I asked Heather Brunskell-Evans for her perspective.

“The thing she (Mary) was very concerned should end in society was the reduction of women to sexually pleasing objects for men and what should also end was women’s complicity by turning themselves into these objects (it circumscribed their capacity for agency, independence and critical thought). That we now have a tiny naked stereotype sexed female body as a gift to her in her honour seems to me to be part of collective madness at the moment about sex and women (pornography as empowering etc.) … but that’s just me, I’m willing to contemplate other views!”

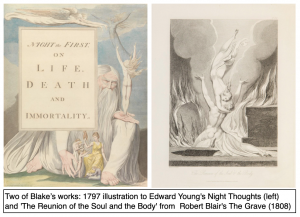

Susan Matthews told me, “I simply can’t make up my mind. I think Maggi Hambling was thinking Blake and I like Blake. I don’t think the figure is pornographic, and don’t see why pornography should own nakedness.”

Matthews pointed me towards two of Blake’s works- his 1797 illustration to Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (left) and ‘The Reunion of the Soul and the Body’ from Robert Blair’s The Grave (1808)- as possible influences for Hambling’s sculpture. Remember that Blake illustrated Wollstonecraft’s children’s book, so this would be an interesting and understandable connection for an artist to make, although not one that Hambling has chosen to acknowledge publicly.

Hamling’s ‘Self Portrait’, (1977/8) National Portrait Gallery

Hambling is notoriously somewhat intimidating, quirkily creative; shrewd eyes poking through lashings of black eyeliner, never without a cigarette. She put forward a project and it was accepted. The public were given a chance to be involved in the choice: some would say why should she explain herself?

Her website on 16/11/20 made no mention of the Wollstonecraft statue, although other recent works were listed.

Get some clothes on

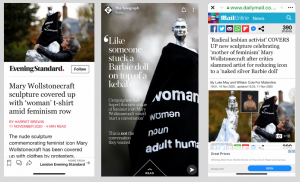

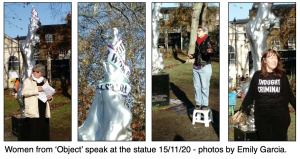

Janice Williams and Julia Long from feminist campaign group Object! made the decision to clothe the statue in protest, and on November 11th ‘Mary’ was quickly clad in an ‘adult human female’ T shirt.

“Mary was tiny, naked, alone, child-size and piled on a base of female body parts. How would she NOT need help?” Janice told me.

The Evening Standard, the Telegraph and the Mail, to name but a few, published articles featuring photos of the Tshirt-clad statue.

I asked Julia Long about her part in the action.

“I walk across the green every day.” she told me. “It was so exciting that there was going to be this statue of Mary Wollstonecraft. I contributed to the campaign myself. I anticipated something that would inspire young girls, that locals would feel proud of, something that would inspire people to find out about her life and achievements. Something that we could all rejoice in.

I just couldn’t believe it when I saw the result of all those years of campaigning and all that money. Just really couldn’t believe it. A tiny, naked, objectified female body on an amorphous mass, that says nothing about the woman or her life. How will that make girls and women feel, walking past? What message does it send out? After all the hard work that went into it, it just feels like a massive wasted opportunity.

Of course, at a time when women and our language are under such attack, it was also a good opportunity to remind people what a woman is. Mary Wollstonecraft’s great work was called A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. It wasn’t called A Vindication of the Rights of Cervix-havers, or A Vindication of the Rights of Menstruators. So it was very fitting to honour the great philosopher of women’s human rights with a t shirt reminding onlookers that a woman is an Adult Human Female.”

What did Maggi Hambling say about the criticism of the statue?

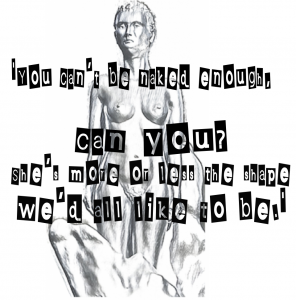

“You can’t be naked enough, can you?

… she’s more or less the shape we’d all like to be.”

Hambling claimed critics had ‘missed the point’, telling the Evening Standard on the 12th, “You can’t be naked enough can you? The point is that she has to be naked because clothes define people. We all know that clothes are limiting and she is everywoman. As far as I know, she’s more or less the shape we’d all like to be.”

Everywoman? This is exactly the point. She is not fucking well ‘Everywoman’. Everywoman does not look like that. Everywoman does not have flawless skin, perfectly perky tits and a flat stomach. Everywoman does not have a fucking thigh gap.

Is that the message those who fought for the sculpture had hoped for? The sculpture whose ‘presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people’?

Is that the message those who fought for the sculpture had hoped for? The sculpture whose ‘presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people’?

Inspirational as in “Fuck, I look way fatter than her, nobody will ever fancy me, better skip lunch.”?

Inspirational as in “Woah, look at the tits on that! Hey Betty, is your bush that hairy?”?

Because let’s not pretend that isn’t what will happen when school kids are hanging out near the statute. We know it’s true because we’ve been and seen schoolkids. Boys will catcall, girls will compare and find themselves lacking, and ‘taught from infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre’ the minds of young women ‘will shape themselves to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage’ see the solution to life’s ills as lying in a new lipstick and a pair of support pants from Primark rather than in education.

‘Mary on the Green’ or ‘Maggi on the Green’?

“I need complete freedom to respond to the spirit of my subject and could not work if constrained by convention or preconceived demands.” Maggi told the Guardian on 14th, in the face of continued media coverage and actions.

“I need complete freedom to respond to the spirit of my subject and could not work if constrained by convention or preconceived demands.” Maggi told the Guardian on 14th, in the face of continued media coverage and actions.

“As Oscar Wilde said, when critics are divided the artist is at one with himself.”

“The problem is this seems to be about an artist’s ego. The fundraising campaign was called ‘Mary on the Green’, not ‘Maggi on the Green’.” retorted Julia Long.

On Sunday 15th, more women from Object! met at the statue. A video of the event ‘Homage to Mary Wollstonecraft’ can be seen here .

Apostrophising Wollstonescraft, Long said, “I’m sure the women are here are really gratified that as we push our buggies with our kids in; maybe go jogging through the park, we we see yet another objectified image of a naked woman on top of a statue that tells us absolutely nothing about your life or your work, everything thing you did… reminded that no matter what you achieve in life, what amazing pioneering work you do, if you are a woman at the end of the day you are just another naked body.”

Another speaker added that the artist and those who chose the statue, “could not have done a better job of erasing everything about the pioneering advocate of women’s rights, intellectual, philosopher, writer and mother that Wollstonecraft was.”

So there we have it. Empowering or not empowering? Appropriate or otherwise?

It’s everything that’s wrong with modern feminism

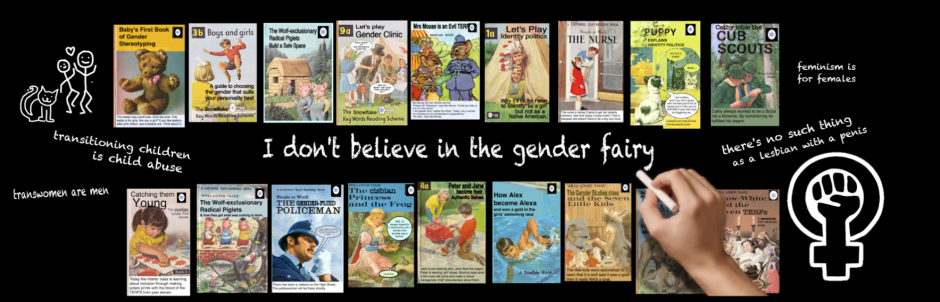

As Julia Long points out, the statue of Wollstonecraft looks as if she has “kept up to speed about what feminism is these days… empowerment through getting naked as often as possible and getting naked women plastered all over the place… getting naked in public says everything about female empowerment far more than a pen and a load of books could do.”

It’s almost as if the statue symbolises everything that is wrong with comtemporary liberal feminism.

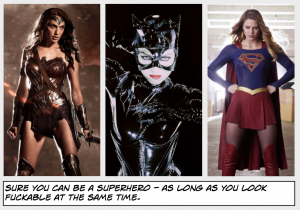

The idea that it’s somehow empowering for a woman to be naked is not generally true. In most situations, in reality, a naked woman is a vulnerable woman. Yet liberal feminism teaches young women that the most desirable superpower of all is to make men want to fuck them. This message is portrayed in a million ways, often subtly, often with the best of intentions. Everything is viewed through the lens of the male gaze. It’s empowering.

To those who say ‘why shouldn’t the statue be naked?’ I would ask ‘Why should she be?’ As a memorial to Wollenscraft, why does she need to be? What is the reason, really?’

How exactly are women supposed to be inspired by this statue of an ostensibly timeless everywoman who just so happens to be ‘more or less the shape we’d all like to be’?

‘Fuckability’ should be the buzzword of 2020s feminism. Its value as a marketed commodity has increased incrementally in the last few decades, accompanied by the pinkification of toys, the sexualisation of young girls’ clothing and the rise of porn culture. In 2020s feminism, everything a woman does is a feminist act but she should always appeal to the male gaze while she’s doing it. This message is portrayed in a million ways, often subtly, often with the best of intentions. The perspective of the male gaze is so all-encompassing that we don’t even see it’s there.

I have lost count of the number of women and girls who’ve told me Wonder Woman is a feminist film.

Liberal feminism doesn’t free women from the chains of objectification, rather it wraps them in sparkles and slathers them with candyfloss flavoured lube while whispering ‘smile’ and enticing them to be ‘sex positive’. The mantra of fuckability is benevolent. It loves to expand it’s definition. It lurks in the doorways of silky underwear shops pushing the “hey fatty, you can look sexy too!” vibe.

The idea that young women should love- or at very least not object to- being naked and exposed to the male gaze is the underlying message when an MP suggests that prostitution is a job option that young women should be encouraged to consider.

It’s why an inspired campaign like ‘This Girl Can‘ sees nothing wrong with the message behind a picture of a young woman in boxing gloves, jewellery and full make-up with the slogan ‘underneath these gloves is a beautiful manicure’.

However much young women may try to fight- sometimes literally- their way out of the gilt cage, they are constantly reminded that their beauty, or less delicately put, their fuckability, is their sceptre.

It underlies this 2016 Evening Standard article about female paralympians. What is really being celebrated? If it is their athletic achievements, why are they bound up in black lace and nylon?

“We think that objectifying ‘diverse’ women is progress.” wrote Meghan Murphy back in 2014. “We think that the male gaze gives us power. But it doesn’t. Because it is a gaze that dehumanizes us. And we want to be human, guys. We want it so bad… because the whole point of feminism is that women should get to exist and be valued as people. Regardless of whether or not you think they are hot.”

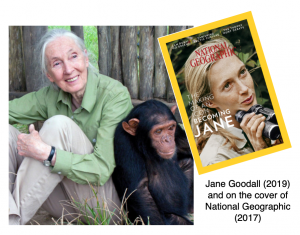

When a National Geographic 2017 edition ran a cover feature on Jane Goodall, called ‘Becoming Jane’, it chose a photograph of her taken almost sixty years earlier. They could easily have used a current photograph of world-leading primatologist Jane, who is still alive and kicking, but it is unlikely as many editions would have been sold without the F factor.

When a National Geographic 2017 edition ran a cover feature on Jane Goodall, called ‘Becoming Jane’, it chose a photograph of her taken almost sixty years earlier. They could easily have used a current photograph of world-leading primatologist Jane, who is still alive and kicking, but it is unlikely as many editions would have been sold without the F factor.

Trying to convince women that they can achieve and maintain this ‘fuckable’ status for as long as possible is a multi-million pound industry. It is never enough. Creams that lighten our skin (as advertised by liberal feminist icon Emma Watson) are sold alongside sprays to ‘bronze’ our skin, diet pills alongside implants. Our bodies should all be hairless, of course. To follow the rules of the game for as long as possible and then retire with dignity demands a special compliance. Criticise the game and you’re a prude. You probably hate sex. Which is a good job because nobody would want to fuck you anyway. You’re bitter. You’re just jealous. You’re a dried up old hag. And, often, you are just too old.

“And, why do they not discover,” asked Wollstonecraft, “when ‘in the noon of beauty’s power,’ that they are treated like queens only to be deluded by hollow respect, till they are led to resign, or not assume, their natural prerogatives?”

When women play a game where patriarchy has set the rules, it is impossible to win, both because it’s not our game and because many of us don’t really even realise the nature of the game we are playing. We have “chosen rather to be short-lived queens than labour to attain the sober pleasures that arise from equality.”

The little silver statue may well be nice enough in her own way, although I haven’t met her face to face yet. But I cannot see how she will inspire women and girls. As an offering to Wollstonecraft she is a sad disappointment, and when I think of her right now all I can imagine is that she is feeling pretty small and vulnerable out there on this dark and wet November night.

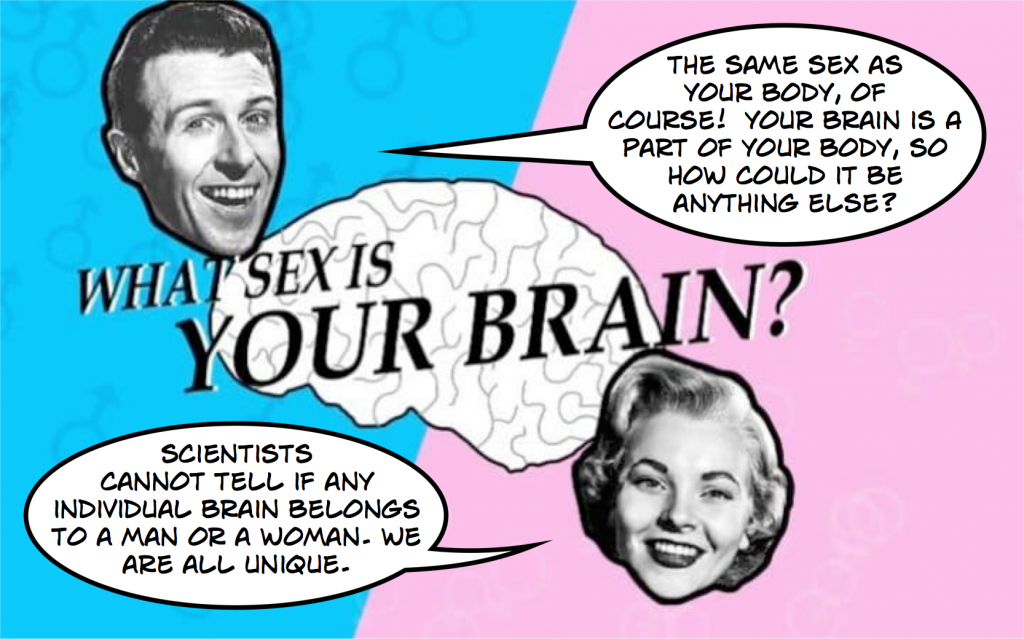

Does the wannabe scientist in you prefer the idea of a male or female brain to the more spiritual idea of the soul?

Does the wannabe scientist in you prefer the idea of a male or female brain to the more spiritual idea of the soul? If you believe in the GS, you will consider the possibility that an effeminate boy or a homosexual young man is not actually male at all. What makes him drawn to the trappings of femininity? Is it that he is a little unusual, perhaps sensitive or imaginative, or could it possibly be that the gender fairy has slipped up again and he has somehow received the soul of a girl? If you believe in the GS, this is rational thinking.

If you believe in the GS, you will consider the possibility that an effeminate boy or a homosexual young man is not actually male at all. What makes him drawn to the trappings of femininity? Is it that he is a little unusual, perhaps sensitive or imaginative, or could it possibly be that the gender fairy has slipped up again and he has somehow received the soul of a girl? If you believe in the GS, this is rational thinking.

Queen Victoria wipes the board with the rest; we have an astonishing 29 statues of her. Unsurprisingly, none are nude.

Queen Victoria wipes the board with the rest; we have an astonishing 29 statues of her. Unsurprisingly, none are nude.

John Opie’s painting of Wollstonecraft (circa 1791) is housed in the Tate Gallery, London. The painting bears this display caption:

John Opie’s painting of Wollstonecraft (circa 1791) is housed in the Tate Gallery, London. The painting bears this display caption:

“I have proposed a statue of her that expresses her heroic courage and her sheer force of personality,” proclaimed Jennings, and suggested this design (right). The statue, cast in bronze and set in stone, would have seating on either side, “to stand in place for at least as many centuries as her reputation has been neglected.”

“I have proposed a statue of her that expresses her heroic courage and her sheer force of personality,” proclaimed Jennings, and suggested this design (right). The statue, cast in bronze and set in stone, would have seating on either side, “to stand in place for at least as many centuries as her reputation has been neglected.” Likewise, if you live or work in London you may well have seen Hambling’s work. Her statue ‘A Conversation with Oscar Wilde’ has stood on Adelaide Street opposite Charring Cross station since 1998.

Likewise, if you live or work in London you may well have seen Hambling’s work. Her statue ‘A Conversation with Oscar Wilde’ has stood on Adelaide Street opposite Charring Cross station since 1998. Hambling is also known for her ‘Scallop’, a tribute to Benjamin Britten. Located on Aldeburgh beach since 2003, described as an ‘iconic image of the Suffolk coast‘, ‘Scallop’ is a six and a half ton, fifteen feet high stainless steel shell bearing the quote, ‘I hear those voices that will not be drowned’.

Hambling is also known for her ‘Scallop’, a tribute to Benjamin Britten. Located on Aldeburgh beach since 2003, described as an ‘iconic image of the Suffolk coast‘, ‘Scallop’ is a six and a half ton, fifteen feet high stainless steel shell bearing the quote, ‘I hear those voices that will not be drowned’. “These are the two shortlisted designs showing how the long-awaited statue of revolutionary 18th century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft on Newington Green could look.

“These are the two shortlisted designs showing how the long-awaited statue of revolutionary 18th century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft on Newington Green could look. Whilst some might say that both ‘Mary on the Green’ and the artist have been clear that the statue is not of Mary Wollstonecraft but for her, contributors to the collection could have been forgiven for having assumed it would be the former. For example, the website mentions how inspiring MW’s ‘presence in a physical form’ will be.

Whilst some might say that both ‘Mary on the Green’ and the artist have been clear that the statue is not of Mary Wollstonecraft but for her, contributors to the collection could have been forgiven for having assumed it would be the former. For example, the website mentions how inspiring MW’s ‘presence in a physical form’ will be.

Is that the message those who fought for the sculpture had hoped for? The sculpture whose ‘presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people’?

Is that the message those who fought for the sculpture had hoped for? The sculpture whose ‘presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people’? “I need complete freedom to respond to the spirit of my subject and could not work if constrained by convention or preconceived demands.” Maggi told the Guardian on 14th, in the face of continued media coverage and actions.

“I need complete freedom to respond to the spirit of my subject and could not work if constrained by convention or preconceived demands.” Maggi told the Guardian on 14th, in the face of continued media coverage and actions.

When a National Geographic 2017 edition ran a cover feature on Jane Goodall, called ‘Becoming Jane’, it chose a photograph of her taken almost sixty years earlier. They could easily have used a current photograph of world-leading primatologist Jane, who is still alive and kicking, but it is unlikely as many editions would have been sold without the F factor.

When a National Geographic 2017 edition ran a cover feature on Jane Goodall, called ‘Becoming Jane’, it chose a photograph of her taken almost sixty years earlier. They could easily have used a current photograph of world-leading primatologist Jane, who is still alive and kicking, but it is unlikely as many editions would have been sold without the F factor.