If you’re reading this, the chances are you know a bit about Transgender Trend already. You might have asked for one of their schools’ packs to be sent to your child’s school or club; you might have referred a friend with a gender-confused child to their website, and you’ve almost certainly heard about the importance of their contribution to the Keira Bell case.

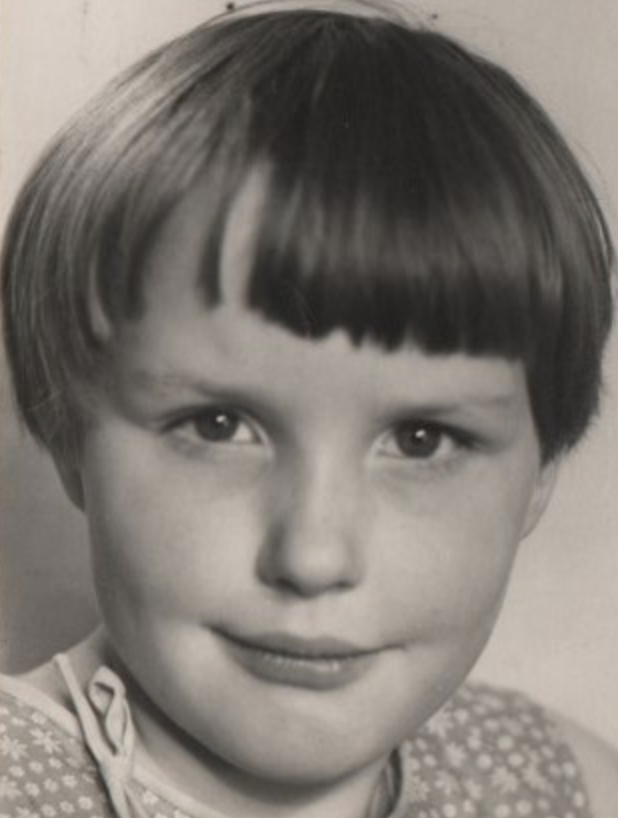

Six-year-old Stephanie

But how did the organisation get to where it is now? And what do you know about its founder, Stephanie Davies-Arai?

How and why did she become so focused on protecting children who don’t conform to society’s expectations of gendered behaviour?

Pop the kettle on, make yourself a cuppa. Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin…

Childhood

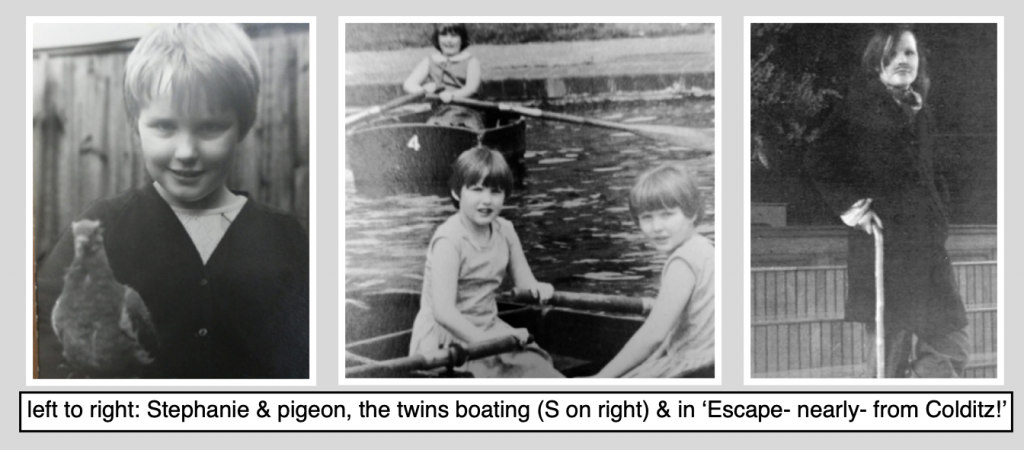

Stephanie (right) “I hated pretty dresses & hair slides.”

Stephanie & her twin sister Helen were born in Chester in the late 50s, hot on the heels of their older sister Gill. Their father was a bank manager and their mother a housewife and librarian, who managed and reorganised information systems for the Leicester police after their move to a small market town when the twins were seven.

“When we were about 6 my parents bought Helen and I toy prams for our birthday: we turned them into tanks and terrorised the neighbours!

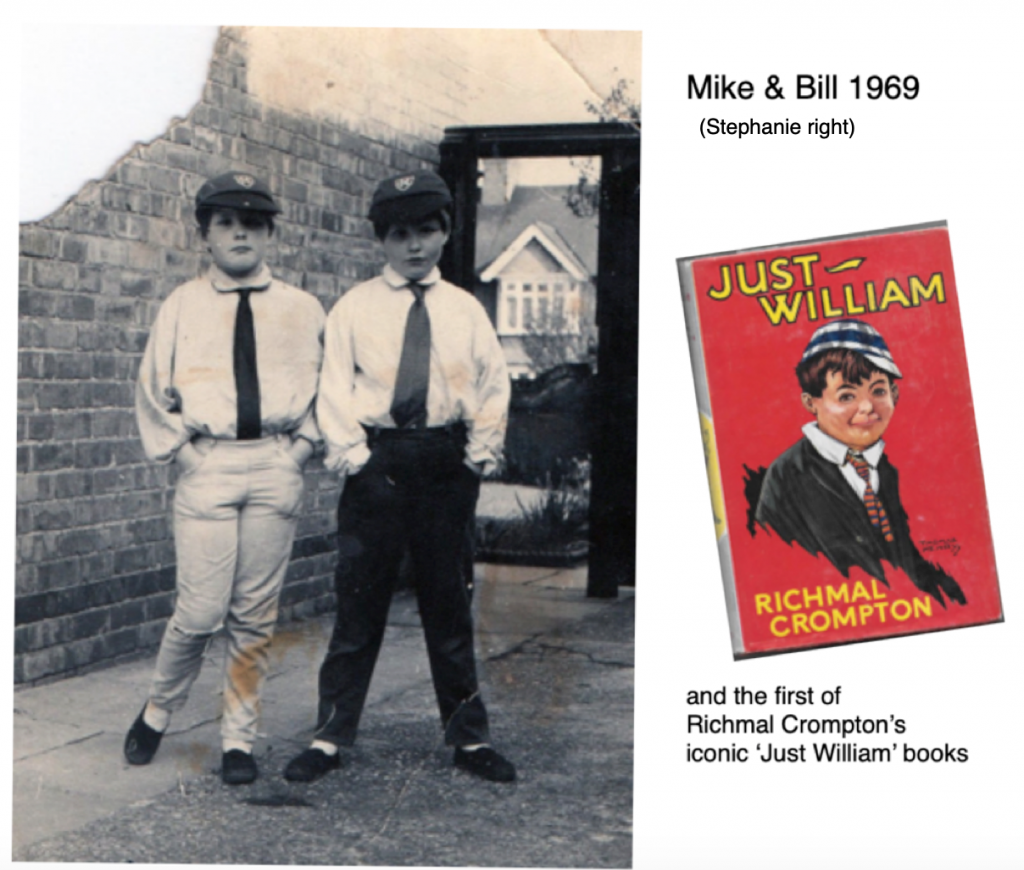

We called each other Mike and Bill and we modelled ourselves on Just William.”

Mike and Bill

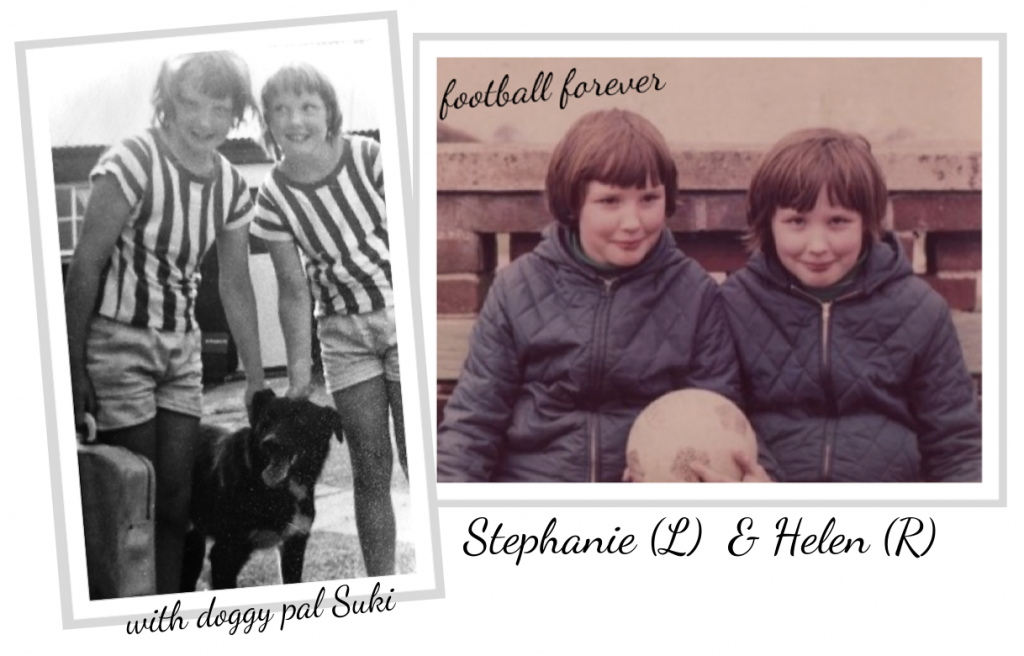

“From the age of seven until we were about twelve, when we lived in Wellingborough, we just roamed free, exploring tips and wasteland where we made fires and cooked potatoes and made liquorice water. That was the best part of my childhood, roaming. We were tougher and more adventurous than any of the boys and we were obsessed with dogs and Leeds United.”

“We were the naughty twins! We wore boys’ clothes, from the boys catalogue, and I remember when I started fancying Paul Blake, who we played football with, I bought a T shirt from the boys’ catalogue thinking, ‘this will make him fancy me’. I was convinced that he would fancy me because I was like him, but it wasn’t long before I had to face the awful realisation that instead he fancied a girl who was very girly.”

Stephanie refers to this time as ‘my typical ‘boy’ childhood’. The twins attended an all-girls school but never fitted in with the more ‘girly’ girls. When puberty struck it was a hard blow. Stephanie found it hard to cope. She developed eating disorders, becoming bulimic.

At fifteen, Stephanie, her twin sister Helen and friend Sue were completely obsessed with the TV series Colditz. They went to school in role as the characters- Stephanie was Flight Lieutenant Simon Carter- and persuaded the school to let them put on a play they had written, “Escape- nearly- from Colditz!”

The other girls in the play were messing around and laughing,” recalls Stephanie, “But Helen, Sue and I were deadly serious.”

Throughout this time Stephanie continued to struggle with eating disorders.

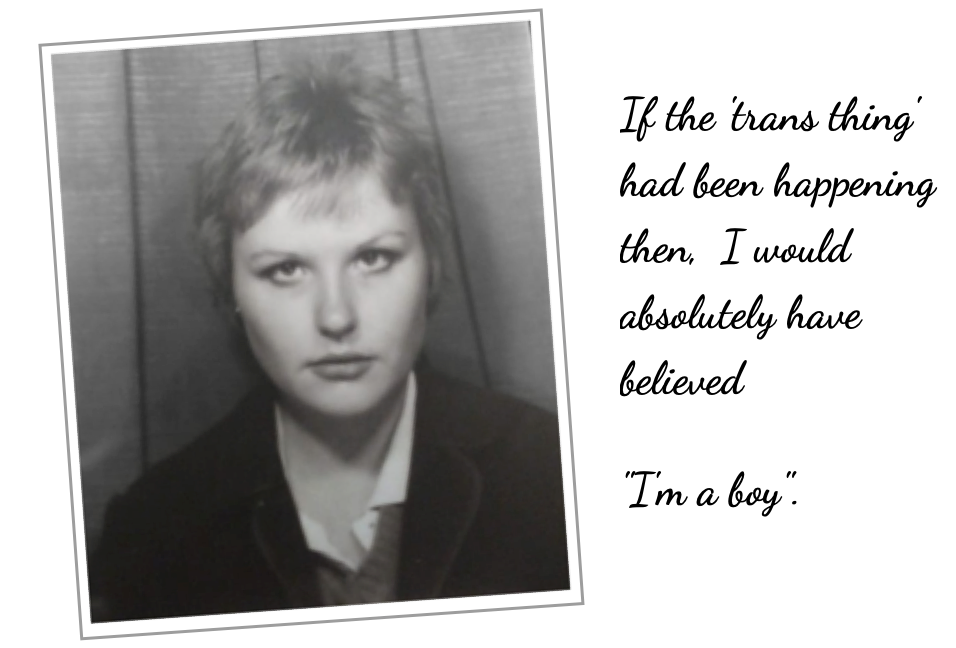

Stephanie (left) & Helen, age 18

“Punk saved me,” she observes, “I grew up in the era of Page 3. ‘Pan’s People’ were on Top of the Pops. Family entertainment was Benny Hill: older men lusting after schoolgirls and trying to escape their boring, nagging wives. There were strippers on in the local pub in Leicester at lunchtime! It was constantly in your face how a woman ‘should’ be.

Stephanie (R) & friend Sue, hitch-hiking

“It was only looking back that I realised I’d imbibed all that and I had a deep internal misogyny. I had a real contempt for anything that was feminine.

I wasn’t like that; I was better than that; I was different to that.

London & Sculpture

“Punk didn’t expect girls to look pretty – if anything quite the opposite.”

Dressed in clothes from the army surplus store, Stephanie left home to attend art college in Newport and study sculpture.

“Despite my cool act, I still had very low self-esteem and eating disorders. I usually weigh about nine and a half or ten stone, but here, in my last year at art college, I was borderline anorexic. I weighed about seven stone.”

“Despite my cool act, I still had very low self-esteem and eating disorders. I usually weigh about nine and a half or ten stone, but here, in my last year at art college, I was borderline anorexic. I weighed about seven stone.”

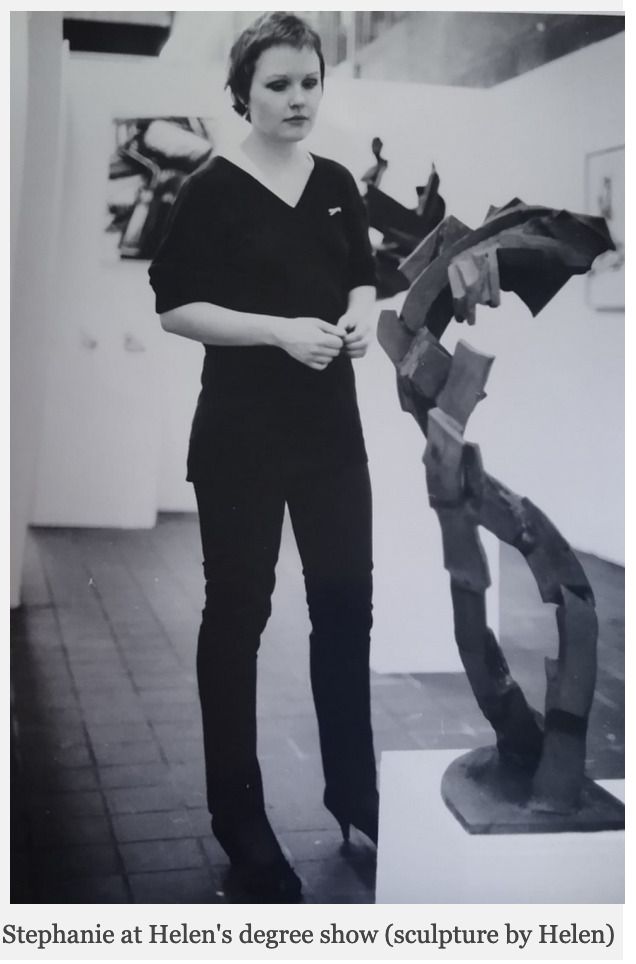

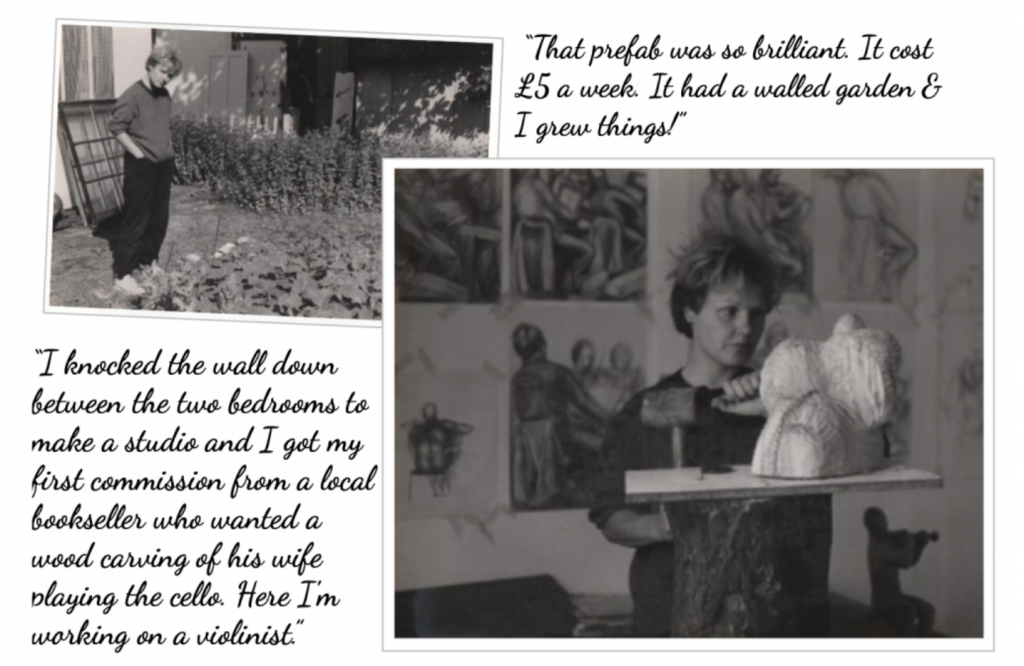

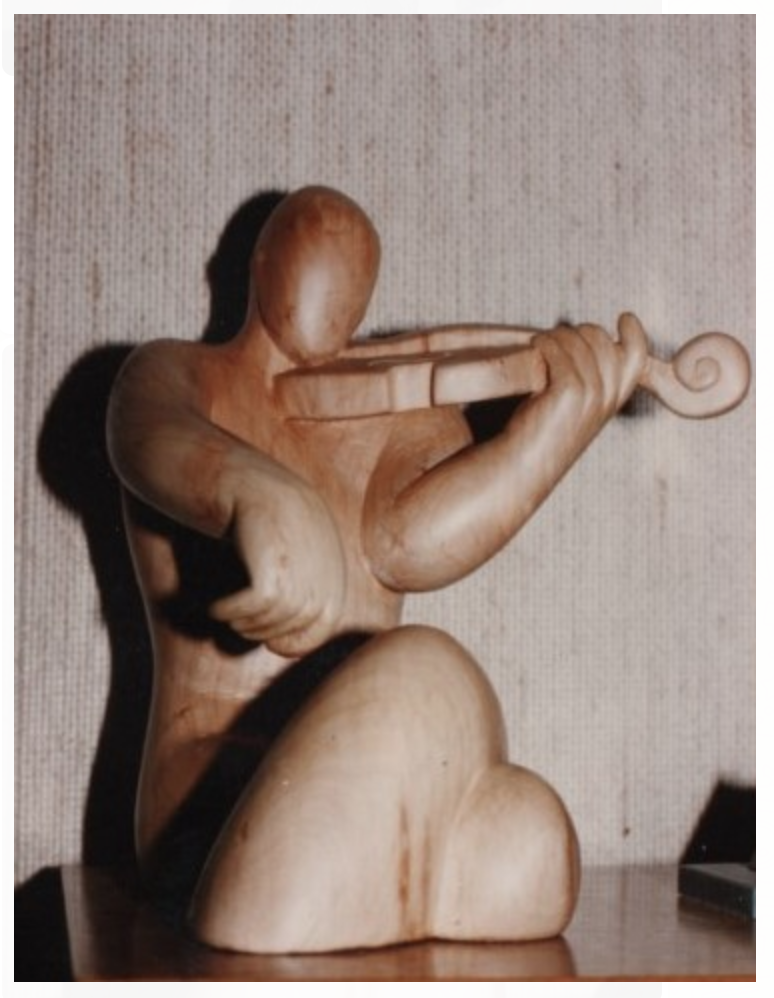

After leaving college Stephanie continued to sculpt, preferring at this point to carve in wood.

She spent the next five years living in a small prefab near the Southbank, where she became an unofficial artist in residence for the London Philharmonic Orchestra, drawing and sculpting the musicians and conductors, including Andre Previn, sometimes selling them her work.

Stephanie’s fascination with the orchestra grew and she began working on small wax figures of the musicians which she cast in bronze.

Stephanie’s fascination with the orchestra grew and she began working on small wax figures of the musicians which she cast in bronze.

Violinist – the finished piece – Stephanie Davies-Arai

A Japanese friend of Helen’s sent some slides of her work to a gallery owner he knew in Tokyo. The gallery was impressed and sent back that they wanted to buy twelve.

On a whim, Stephanie decided to deliver them herself. Feeling the need to escape London for an adventure, what was planned to be a three-month trip turned into a stay which lasted over five years.

While in Japan Stephanie taught herself to speak the language and enrolled at art college in Kanazawa, Honshu. It was here that she taught English while learning to carve in stone and study for her MA, writing her final assessment essay in Japanese.

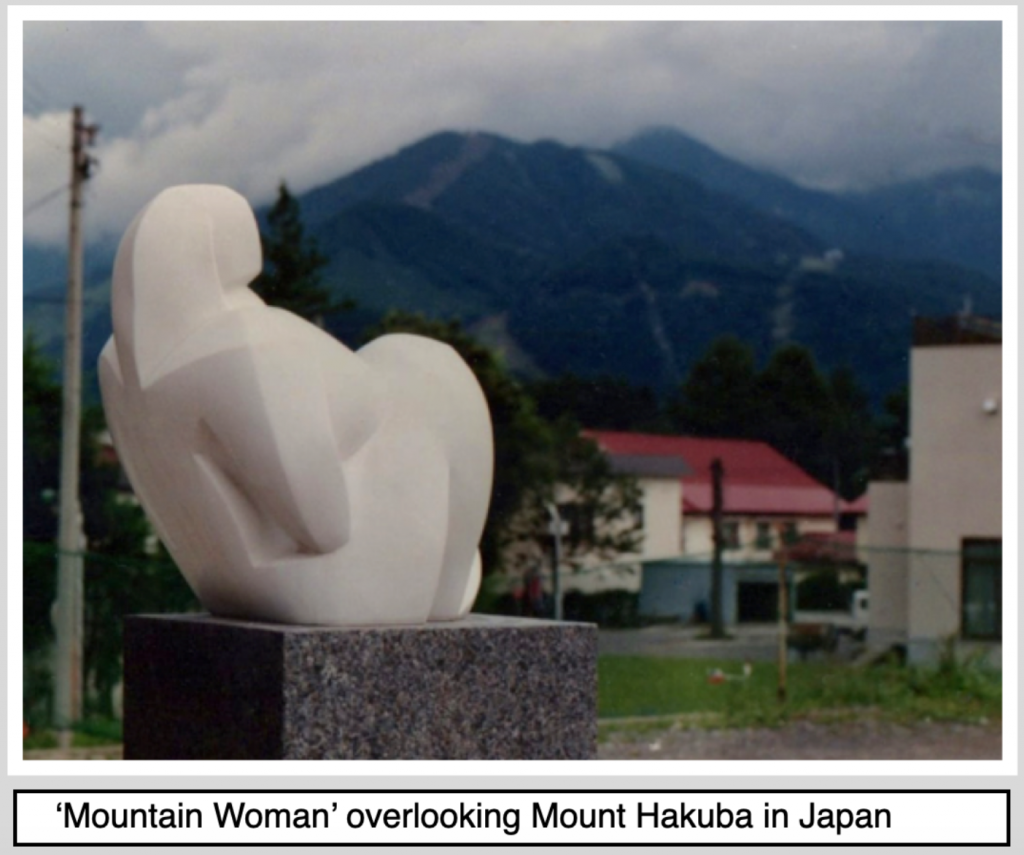

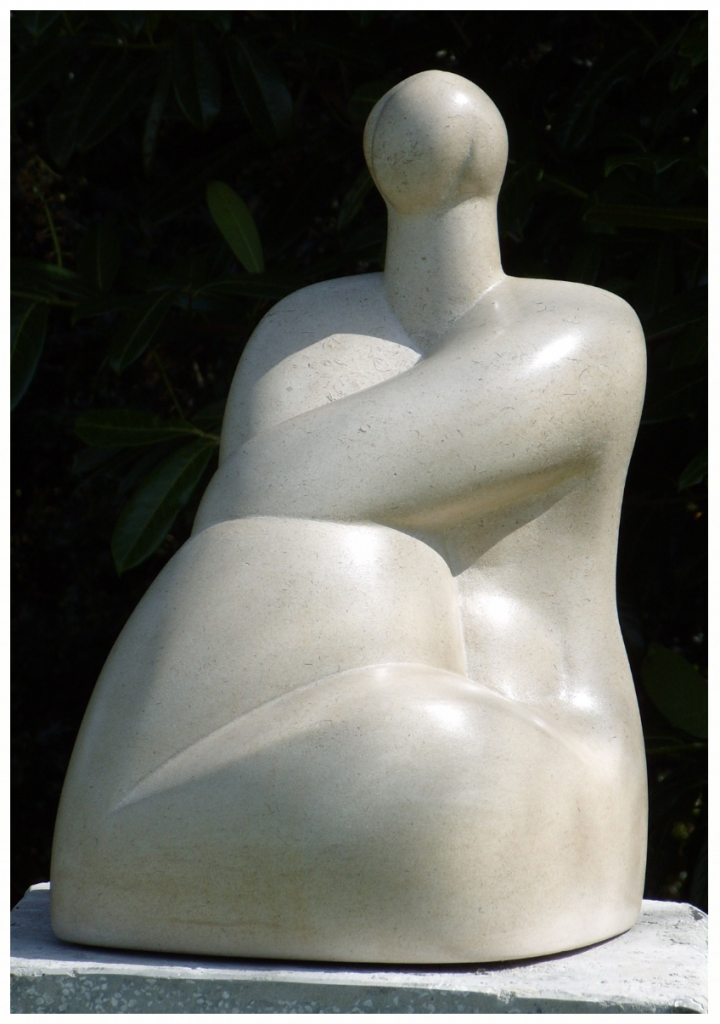

In 1998 she was commissioned to create ‘Mountain Woman’, a large marble sculpture which was set on a plinth in Nagano, gazing out over Mount Hakuba.

“Right in front of a public toilet!” laughed Stephanie.

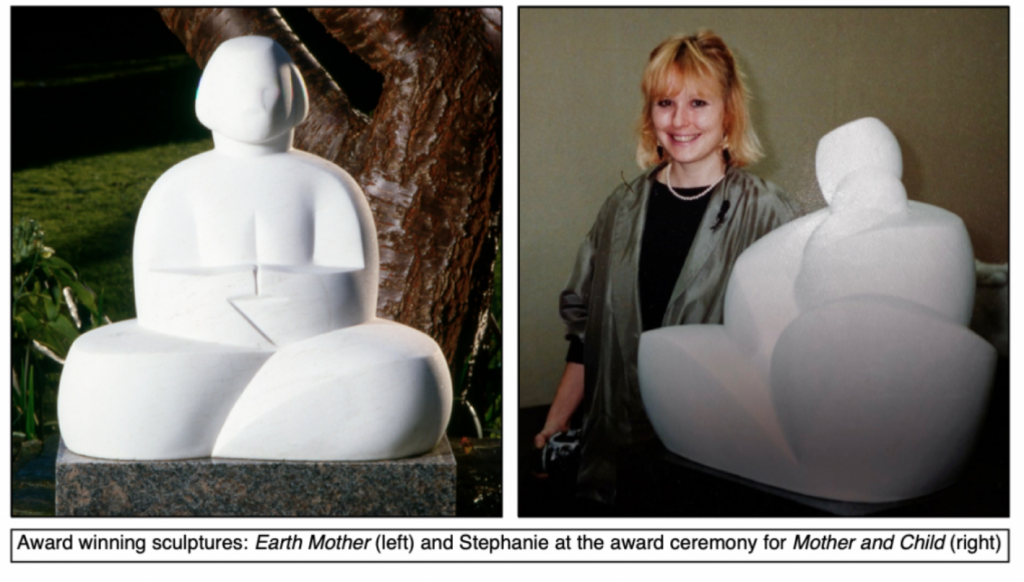

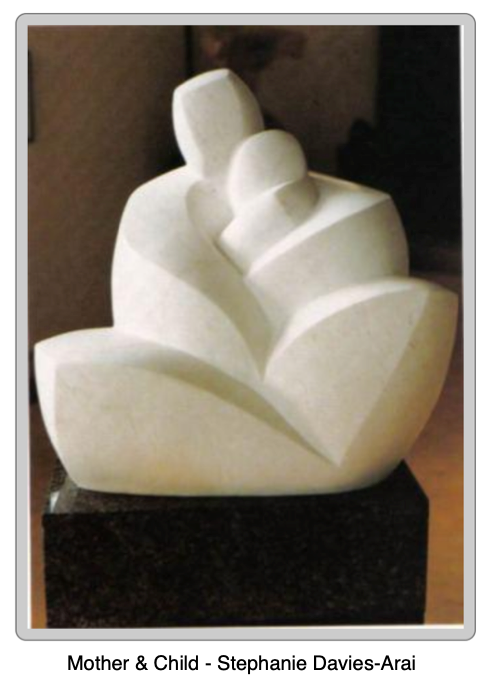

In 1990 Stephanie won the Fukui Television Prize at the 28th Hokuriku Chunichi Annual Exhibition of Art in Kanazawa for her sculpture Mother and Child. In the same year she won the Kanazawa Chuo Lion’s Club Prize at the Hokoku Shinbun Annual Exhibition of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa for her sculpture Earth Mother.

Pregnant Stephanie visiting ‘Mountain Woman’ in 1991

Stephanie met her husband here and it was here she gave birth to her first child.

“It was really only when I became pregnant that my eating disorders disappeared.” Stephanie remembers. “I lost that need to control what I was eating and my body took over. My first three children were boys. I was comfortable having boys because I felt I could relate to them. I think it was only after the birth of my fourth child, my daughter, that I fully threw myself into embracing being a woman.”

The prize money and high number of commissions she was receiving enabled Stephanie to give up her teaching work and sculpt full time.

Wonderful as it was to be earning enough money to live on from her sculpture, Stephanie missed English humour and irreverence, and was concerned about the demands placed on children by the highly structured and formal education system which forms a mainstay of Japanese culture.

England, Art and Motherhood

When their son was just six months old, Stephanie and her husband returned to England, where they settled in the South and had three more children.

“That was my thirties gone!” she jokes. “There was me who never wanted children, never wanted to get married, and I became an earth mother! We both worked from home because we wanted to be there with the kids.”

Stephanie continued to sculpt, but making a living from her art in England was not as easy as in Japan, especially with a growing family.

“There’s so much opportunity for winning prizes and getting commissions in Japan, but in England there was very little.”

In 2008 Stephanie split from her husband. They remain friends and he often cooks her delicious Japanese food.

Figure with Animal – Stephanie Davies-Arai

“This is my fave pic of me sculpting. I had this outdoor studio for years when the kids were little. I just wanted to be the person in the steel toe-capped boots wielding an angle grinder and heavy stone chisels.”

Stephanie continued to take commissions. The piece she’s sculpting in the above photo now sits in the grounds of the RSPCA headquarters in Horsham.

The inscription on the plinth is a quote from Anatole France:

“Until one has loved an animal, a part of one’s soul remains unawakened.”

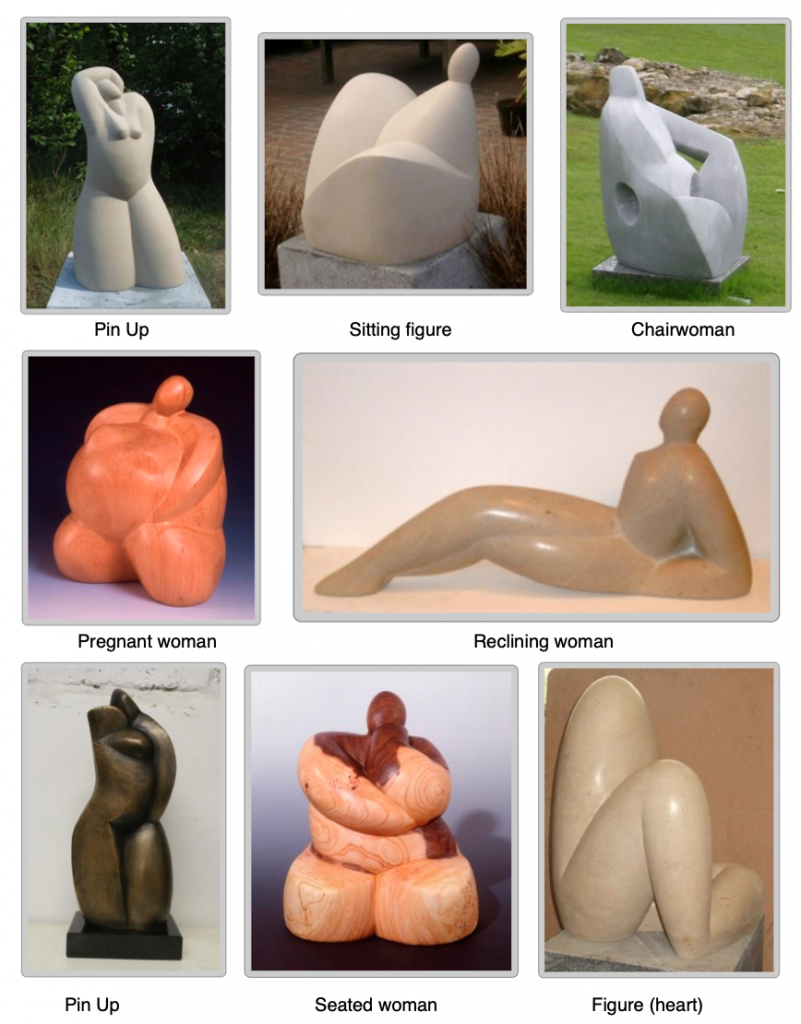

“I love sculpture because it occupies space in the real world. I wanted to fill the world with figures of women proudly taking up space and owning it.”

You can see more of Stephanie’s sculptures here on her sculpting website.

Communicating with Kids

“My first child was very difficult, so I went on a parenting course. I really liked the course because it was based on communication skills and relationships rather than punishment and reward.”

“My first child was very difficult, so I went on a parenting course. I really liked the course because it was based on communication skills and relationships rather than punishment and reward.”

Stephanie was so taken with the parenting course that she trained to run it herself, first for parents and later for teachers. When the family moved to Lewes she became a founder member of the Lewes New School, a small, progressive, independent school.

“We wanted it to be disciplined, not a free-for-all but freedom within structure.”

Her involvement came about in part from concern that her eldest child would be judged and labelled in a mainstream school. Stephanie was a parent governor and her main role was working with parents, teachers and kids: designing policies for respectful communication and other school policies, including anti-bullying and behaviour policies. She worked at the school for eight years, running peer mediation programs and teacher training and parenting courses at the school.

It was at this time she became increasingly aware of the flaws in the course.

It was at this time she became increasingly aware of the flaws in the course.

“It was too child-centred. It kind of treated children as victims in a way, as if they always had a problem. It didn’t seem to give permission for parental authority.”

The school had a lot of school-refusers, ‘problem’ kids and autistic kids. Stephanie began working out her own strategies that were ‘much tougher’ than those she was teaching and weaving these into her work. The feedback she received form parents were that those added aspects really seemed to work.

Eventually she decided to design her own course, ‘Communicating with Kids- what works and what doesn’t’. Researching and compiling the course led to the publication of a book with the same name in 2014.

The book, based on clear, direct communication, is “all about how we talk to children and how children understand what we say, including our hidden messages. People still say to me, ‘that book has changed my life.”

If you would like to order a copy of ‘Communicating with Kids’, contact Stephanie at [email protected]. Alternatively you can purchase it here on Kindle.

Stephanie had to make a difficult decision- to carry on sculpting, or to fully commit herself to research and running training courses for parents and teachers. Transporting stone sculpture to exhibitions is an expensive matter but Stephanie continued to exhibit and sell her creations for several more years. In addition to exhibiting in the Cork Street Show she was selected to exhibit in 2010 and 2011 at the prestigious Annual Sculpture Exhibition at the Harold Martin Botanic Garden, her work exhibited alongside sculptors such as Lynn Chadwick.

Eventually she made the decision to give up her studio and concentrate on her other work.

No More Page 3

In 2012 Stephanie joined the ‘No More Page 3’ campaign, drawn in by the extent to which Page 3 had affected her as a girl. During this time she gave radio interviews and presentations, including to Girl Guiding groups, the Co-op and in schools. She also began researching objectification and giving presentations at universities.

In 2012 Stephanie joined the ‘No More Page 3’ campaign, drawn in by the extent to which Page 3 had affected her as a girl. During this time she gave radio interviews and presentations, including to Girl Guiding groups, the Co-op and in schools. She also began researching objectification and giving presentations at universities.

“The lad culture was awful. I learned on the front line of young women’s experiences at universities. I heard women saying they would go out wearing two pairs of tights so that men couldn’t put their fingers up them! Some of the young women were viewing that as normal behaviour. They just weren’t angry enough. It gave me insight into the awful sexist, misogynistic lad culture across universities and how cowed girls were. When I gave presentations about Page 3 there would be men in the audience and it was as if women were too afraid to say, ‘we don’t like Page 3′. I really felt we had gone backwards.”

Stephanie & her fellow ‘No More Page 3’ campaigners

It was during her work on the ‘No More Page 3’ campaign that Stephanie became aware of what she referred to as ‘the trans issue’. It arose as the group were deciding whether to retweet an event; some were saying they shouldn’t share it because it excluded transwomen. Stephanie felt that if they retweeted events that included transwomen but not those that didn’t, the result would be excluding the most vulnerable women, those who needed single sex spaces.

As ‘No More Page 3’ was a single issue campaign, campaigners had to appear neutral on any other issue. As time went on, Stephanie felt it was more and more important that she started writing about the trans issue. She began collecting articles and information. At the same time she was running courses and working with parents and couples, teaching communication skills. Suddenly it seemed as if gushing press stories about happy trans kids were everywhere.

Transgender Children

Stephanie’s own favourite of her sculptures: Decorative figure (after Matisse) 44 x 31 x 25 cm

“That was immediately to me a huge red flag. We’re telling boys that they are girls? We’re telling them a lie. They’re not girls. They are male children, which by definition means they are boys. I think my first thought was that this was the most off-the-wall, crazy parenting advice I’d ever heard!

You’re validating a child’s false belief. You wouldn’t get that in any other area, in any parenting book. It’s not healthy when listening to your child becomes so key that it becomes ‘you must agree with your child’. If you believe that your child knows best, you’re then supposed to follow the child. The child becomes the adult and the adult becomes the child.”

Stephanie explains that the strategy of always asking a child how events make them feel can result in making the feelings more powerful than the child. The feelings become the most important thing. In the 50s and 60s, she observes, children weren’t really listened to at all and we’ve over-compensated for this: often with negative results. Some children who have undergone trauma therapy report that the therapy was a worse experience than the original trauma. Much parenting advice is written by child therapists, with the result that the parent becomes the therapist of the child. If a child doesn’t have problems they can actually be created through a therapeutic approach.

Stephanie wrote a weekly parenting blog at the time, and noticed that whenever something was happening in the parenting world or in education, everybody was discussing it. Not so with the trans issue.

“There was absolute radio silence,” she recalls.

As nobody else was writing about, or challenging, the idea of transgender children, Stephanie felt she had a responsibility to do so.

“Looking back, the gestation of Transgender Trend started even then. I felt ‘this is so, so wrong, somebody needs to challenge it’.”

Eventually- after reading yet another article about trans children and affirming parents- Stephanie published her first piece on the issue, ‘Is my Child Transgender?’, on her parenting blog in March 2015.

“It’s hard to imagine now how silent the world was on this issue back then. Nobody was speaking out. There were some feminists who had written pieces on the issue but their publishers had turned them down. In the parenting world and in the media there was no challenge.”

At the time Stephanie wrote blogs for Mumsnet, Britmums and Huffington post. She observes that the commissions from Mumsnet dried up after she started writing about trans kids. Realising that she was dealing with a massive political issue, Stephanie was initially terrified of putting her article on the Britmums website.

“That’s how intimidating it was. I thought I’d lose a lot of followers. It was a huge risk to take with my parenting blog; my brand; my business.”

In the event, the piece on Britmums didn’t get much traction but Stephanie received numerous private messages of thanks and relief from her subscribers; both from people who had been feeling the same concerns and from parents grateful to see someone airing the issue. But the news wasn’t all good.

“My ‘No More Page 3’ gang were horrified by my position. In the end I felt I needed to leave because I’d caused upset within the team. It was awful to realise that these people who knew me well, loved and trusted me, suddenly thought badly of me. I had been a mentor to some of the younger, troubled, women but suddenly they saw me as a bigot. It was so hard for me to be rejected from my group, to be seen in that way – and I thought, how hard would this be for a young woman at university? At that age, social exclusion is death.”

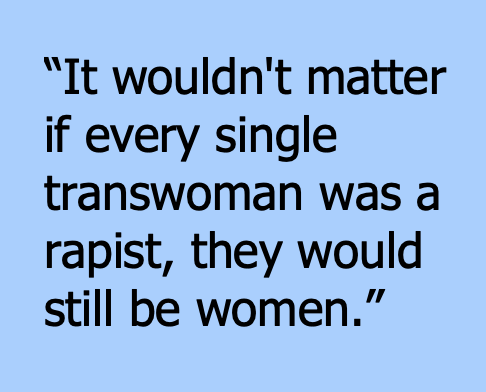

Stephanie said to one young woman, ‘Well what about a rapist? Do we say that person is a woman?’

Stephanie said to one young woman, ‘Well what about a rapist? Do we say that person is a woman?’

She replied, ‘It wouldn’t matter if every single transwoman was a rapist, they would still be women.’

“The absolute madness of it all really revealed itself to me at that point.

“Women can’t speak. Universities are full of intersectional feminism: queer theory identity politics clubs – they’re not feminist. They’re for everyone of all identities. This is what young women are brought up on, these lies, sex work is empowering; transwomen are women.”

Two further pieces followed on the ‘Communicating with Kids’ website, in May 2015, ‘Transgender- a parents’ guide’ part one and ‘Transgender- a parents’ guide’ part two.

“Looking back, it suddenly occurs to me,” reflects Stephanie, “that maybe, partly, why I had the courage to speak out about the trans issue was because, despite the fact that the world was silent, my sister Helen and I were talking about it. I almost still feel that something’s not quite real until I’ve told Helen about it! There was one person I could say anything I wanted to. I couldn’t talk about it to anybody else and I wonder how much more courage that gave me, just that I had that one person I could tell and we could talk about the subject honestly. I wonder how different things would have been if I hadn’t had her to talk to.”

Organising and networking internationally

After the publication of these pieces, Stephanie realised the way forward was to make a separate website and form an organisation, so the media had somewhere to contact for a voice of challenge to the current narrative. The rest of 2015 was spent planning and building the Transgender Trend website. A huge amount of research was involved. Stephanie knew that it was essential for the website to be a factual, research and evidence-based resource for parents, gathering all the essential information in one place.

“Parents were looking online and all they were finding were Mermaids and Gendered Intelligence. These organisations were just sending them propaganda and ideology: ‘Your son is now your daughter, you must affirm her as your daughter or bad things will happen.“

After the publication of Is my Child Transgender? Stephanie was contacted by 4thwavenow and they formed an email group with parents from the USA, Canada and the UK. Here she began to understand more of the suffering of parents who were going through the experience of having a trans-identified child. Many of them were beside themselves with worry, having no support and often vilified by those around them for not blindly supporting their child’s transition.

After the publication of Is my Child Transgender? Stephanie was contacted by 4thwavenow and they formed an email group with parents from the USA, Canada and the UK. Here she began to understand more of the suffering of parents who were going through the experience of having a trans-identified child. Many of them were beside themselves with worry, having no support and often vilified by those around them for not blindly supporting their child’s transition.

Stephanie wrote a piece for Huffington Post about what these parents were going through, but for the first time, Huffington Post did not publish her work.

This was the start of what Stephanie calls ‘my international adventure’.

“The idea was that we needed an international organisation and I offered to do the website which I was already working on.”

“The name came up from the parents I was speaking to at the time. I thought of ‘let kids be kids’ but that was taken. It was ‘transgender trend’ that these parents told me they were typing into search engines when they were looking for information on the internet.

I’m really glad I called it that: it does what it says on the tin. It is a trend, a very recent trend. Trend is a neutral word, it doesn’t just cover the idea of something being ‘trendy’. That name is what made the media, parents and professionals contact me; anybody searching for information.”

In August 2015 Stephanie sent in a written submission to the Women & Equalities Committee Transgender Equality Inquiry, which was very low-profile at the time. No women had been invited to give oral evidence at the enquiry. She describes the inquiry’s recommendations as ‘a transactivists’ wish list’, with claims unbacked by any evidence. “Claims, including the suicide figures given to them by Mermaids, had all been taken at face value.”

“In October 2015, The Wales Arts Review published Stephanie’s article ‘The Transgender Experiment on Kids’.

“In October 2015, The Wales Arts Review published Stephanie’s article ‘The Transgender Experiment on Kids’.

She remembers that WAR were very supportive at a time when other outlets were unwilling to deal with the subject.

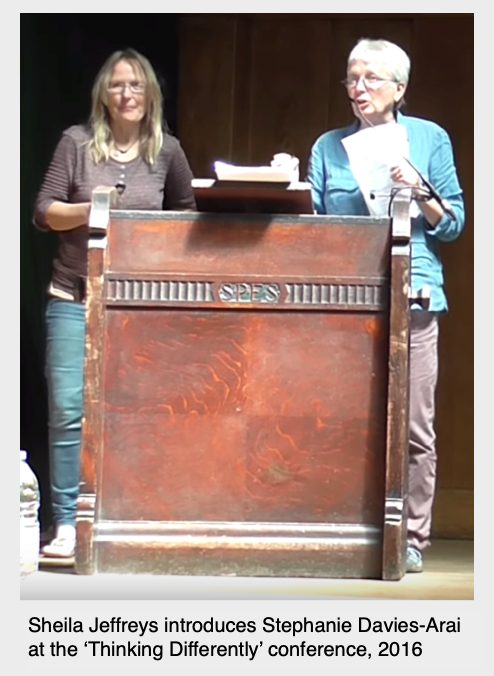

After the October 2015 FiLia conference, Stephanie was invited by Angela C Wild to meet up with a group of lesbians. She talked with them about the organisation and the forthcoming Transgender Trend website. They formed an email group together and Stephanie’s communication with Sheila Jeffreys, inspired her to read Jeffreys’ book ‘Gender Hurts’.

The birth of Transgender Trend

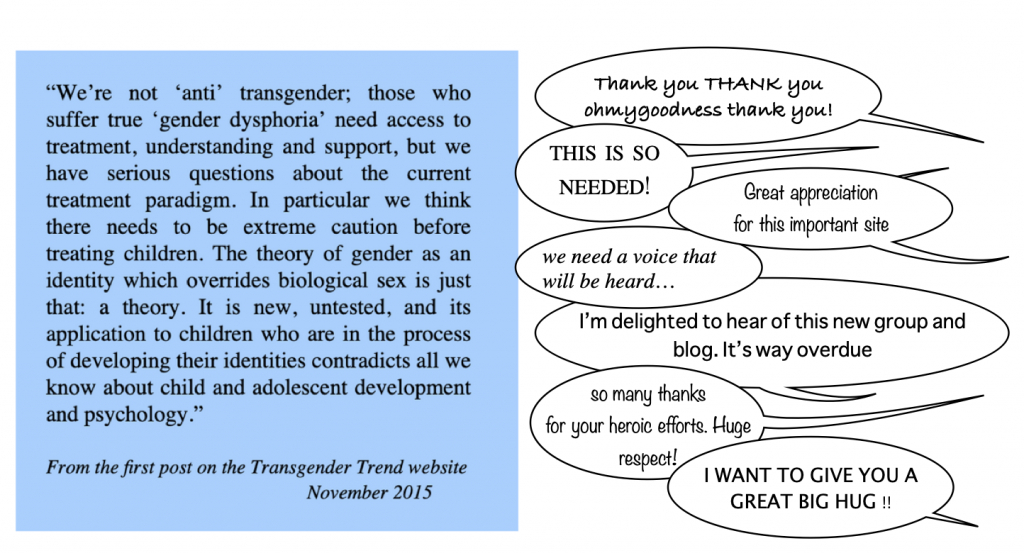

In November 2015, the Transgender Trend website went live.

In November 2015, the Transgender Trend website went live.

After the launch of the website, Stephanie quickly realised that there was so much happening in this country that it would be better for the site to become UK based rather than international. Trying to take on what was happening in such a huge country as the US, so far away, with so many different states and so many different laws governing them, seemed too much. There was more than enough to be done here in the UK. The help she had hoped she would receive did not materialise and Stephanie began having serious doubts that Transgender Trend would work as an international site.

The deciding factor was when Stephanie discovered that someone was referring to themselves as the US spokesperson for Transgender Trend without even having mentioned it to her. Awkward as it was at the time, she decided to disassociate Transgender Trend from countries outside the UK.

“I knew at that time the voice was critical and the message was critical. I couldn’t go in all guns blazing… I had to go in very carefully and the message had to be bang on. I couldn’t trust it to someone in the USA, someone I didn’t know, who might not get the tone right. I also felt that if we wanted to be taken seriously in the UK, it had to be a UK site.”

For the first week after launching the site, Stephanie remembers, there were performance issues: the website would not display properly.

“I was at the end of my tether! That’s when @neverfallingfo1 stepped in to help me sort things out. She’s been with me right from the start. She saved me! It was a week of such stress.”

The first post on the website began:

“Welcome to Transgender Trend. We have set up this website with the aim of providing an alternative source of evidence-based information which questions the theory, diagnosis and treatment of ‘trans kids.’… “

Response to that first post showed what a huge need there was for such a site. Comments poured in from parents, including the following:

Thinking Differently

In July 2016, Julia Long, who had also been involved in the email exchanges, set up the ‘Thinking Differently– Feminists questioning gender politics’ conference at Conway Hall in London.

In July 2016, Julia Long, who had also been involved in the email exchanges, set up the ‘Thinking Differently– Feminists questioning gender politics’ conference at Conway Hall in London.

The conference described itself as ‘the first conference of its kind to present a feminist critique of the politics and consequences of transgenderism and gender identity’.

Stephanie was invited to speak to the 230 attendees. She was introduced by Sheila Jeffreys and spoke alongside Julie Bindel, Juila Long, Lierre Keith, Jackie Mearns, Mary Lou Singleton and Magdalen Berns.

“When you’re doing something and it feels like the whole world is against you, those connections are so, so important. It’s so important to know that people are backing you.”

“That weekend was the same one that Heather Brunskell-Evans, Michele Moore, Lisa Marchiano and detransitioner Carey Callaghan had arranged to meet in Leicester. I couldn’t meet them in Leicester because of Thinking Differently so they came to the conference and we met there. I missed Latitude Festival to do Thinking Differently! Can you imagine what a sacrifice that was for me?” She is only half joking.

“I missed a musical festival!” she repeats.

“It (Thinking Differently) was an historic event. The first one. It really, really was important. Because again, nobody was speaking out at the time and at Thinking Differently women could talk honestly about the trans issue. It was hugely significant for women to be able to do that. I was so glad that I took part. It was good for me because it was a vindication of my work with Transgender Trend. Some of the accusations are so awful- for example being told ‘you want to kill trans kids’. When you’re doing it out of care for children and your motives are presented as the opposite, it’s really hard. So to see that women were grateful to me for what I was doing, was so important. You need that feedback because when you constantly get one message you can begin to doubt yourself.”

At this time Stephanie was still running Communicating with Kids and writing her CWK blog. She had recently developed a ‘communicating with teens’ course and in that she had included a section on gender identity. In addition to working with parents and running courses, she was being invited to give talks on feminism in schools.

“Going into schools to give talks on feminism became really scary because I’d stand up there and I’d think ‘where’s the nonbinary or trans kid in the crowd whose googled my name?'”

A Voice in the Media

Stephanie Davies-Arai & Susie Green on Newsnight with Evan Davis, November 2016

One of the first things Transgender Trend (TGT) did was put out a press statement and ensure that media outlets received it and knew who they were. Transgender Trend quickly gained a voice within the media.

In January 2016 Stephanie was interviewed on Sky News in Brighton after children at a local school were set a survey for homework which required them to choose from a list of 23 terms to describe their gender – ‘girl’, ‘boy’ and any one of 21 other options.

Feeling confident in the knowledge that supportive friends from a facebook group were all watching, Stephanie concluded the interview by saying, “But if these (trans-identified) kids were left alone, most of them would grow up to be gay- it’s homophobia!”

“I remember seeing the face of the presenter,” she remembers.“I don’t think he’d heard that argument before.”

“It was the first time we’d seen somebody on ‘our side’ speak on television on the issue. I wish I had a screenshot of that Facebook page with all the reactions! Then of course you go on to do other things and people start taking you for granted, but for that day I was a real hero!”

From there, people began talking about how alternative schools’ guidance was needed. Stephanie knew that if parents wanted to challenge schools’ guidance they needed to be able to offer a viable alternative that wasn’t an activist manifesto.

As Transgender Trend took up more and more of Stephanie’s time, she realised it was quickly becoming a full time job. Work from schools had started to dry up, mostly because she wasn’t promoting it as much. Mumsnet had stopped asking for guest blogs, which may or may not have been a result of Stephanie’s views and her increased profile in the media.

Stephanie rolls her eyes at the absurd idea that Trangender Trend is funded by the far right. Having worked for nothing for so long, she describes her financial situation as ‘always having been precarious’. Self-employed with no pension, renting her home, it wasn’t long before her income dropped and she had gone through her savings to the point where she was entitled to housing benefit and tax credits.

Stephanie rolls her eyes at the absurd idea that Trangender Trend is funded by the far right. Having worked for nothing for so long, she describes her financial situation as ‘always having been precarious’. Self-employed with no pension, renting her home, it wasn’t long before her income dropped and she had gone through her savings to the point where she was entitled to housing benefit and tax credits.

“I thought: I’m being stupid here, I’m doing something that’s losing me money when I should be building a business, but I couldn’t just stop. I felt like nobody else in the parenting or teaching world was speaking out and somebody had to. I could see what was happening and I simply could not just sit back and watch it happen. I was always very careful to come across as measured, but I was so, so angry at the abuse of children that I was seeing. Indoctrination, psychological abuse, lying, deception, and then medical intervention. Children were being sold the message that to be their authentic selves they had to medically damage their bodies. What a betrayal of this generation.”

In late 2016 Stephanie appeared on Newsnight with Evan Davis and Susie Green, founder of Mermaids and mother of ‘trans teen to beauty queen’, Jackie Green.

“We conflate the terms gender and sex but actually it’s not possible to change from male to female: that’s a biological impossibility.” professed Stephanie, going on to point out that gender is a socially constructed idea of how boys should behave and dress and how girls should behave and dress, and yes, that’s fluid. Teaching children that you can change from a boy to a girl is not being honest with them, she asserted, and in order for ‘trans’ children to become their ‘authentic selves’ they need to be medicated for life. Susie countered that puberty blockers were reversible and that trans children don’t desist.

You can see the full seven minute debate here.

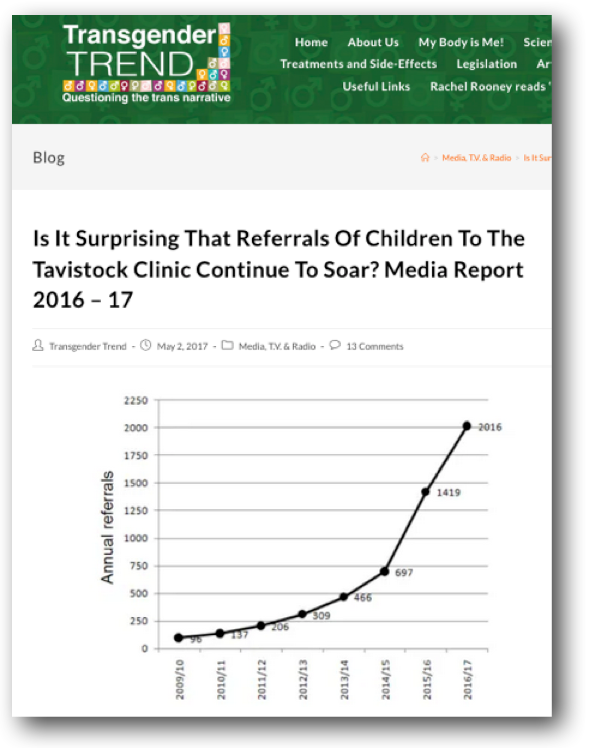

In May 2017, Transgender Trend published a detailed report, “Is It Surprising That Referrals Of Children To The Tavistock Clinic Continue To Soar? Media Report 2016 – 17”

In May 2017, Transgender Trend published a detailed report, “Is It Surprising That Referrals Of Children To The Tavistock Clinic Continue To Soar? Media Report 2016 – 17”

“I got a huge team of women onto the newspapers, on and offline, to see what the media was saying about trans kids. Nic Williams collated it all together and made some really clear graphs. The finished result totally showed how reporting on the issue of trans kids was based on stereotypes. It was obvious that there was no challenge to the narrative or any clinical analysis in the media”.

It wasn’t until Stephanie was writing a blog post, a roundup of what had happened in 2017, that she realised that it was also in the second half of 2017 that journalists in the media- for example Gilligan, Turner and Sanchez- started speaking out.

“That report received a lot of attention,” muses Stephanie. “It contained a lot of accurate information. I like to think it helped to make that impact.”

Schools’ Guidance

“In November 2017 I saw that the Equalities and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) would be bringing out their national guidance in March 2018 and that they had consulted with Stonewall, Mermaids, GIRES, Gendered Intelligence, Allsorts- all the transactivists groups. I wrote to the EHRC and told them I’d like to be a stakeholder in this group. We set up a meeting and half a dozen of us went along.”

At the meeting Stephanie pointed out that while the EHRC initial technical guidance was good concerning toilet facilities (it said a trans child should be found an alternative provision rather than be given access to the toilets of the sex they identified with) she was concerned that they recommended an affirmation approach which said teachers must use preferred names and pronouns and ‘treat a child as their preferred sex’. This, she suggested, was as an activist approach with no evidence to support it.

After the meeting she sent the EHRC a briefing document laying out her concerns and recommendations. Knowing that the EHRC guidance was due to be published in March, she and her small team worked flat out over the Christmas holidays to get Transgender Trend‘s own guidance ready by the February half term.

Producing the schools’ packs was a project very much founded upon Stephanie’s prior communications skills work. The packs contain a legal section which was checked by two lawyers; a section on current evidence, so teachers have access to facts and information; including the human rights of the child and statutory safeguarding.

Producing the schools’ packs was a project very much founded upon Stephanie’s prior communications skills work. The packs contain a legal section which was checked by two lawyers; a section on current evidence, so teachers have access to facts and information; including the human rights of the child and statutory safeguarding.

The resource pack correlated facts and figures concerning autistic children and facts and figures about desistence rates, as well as testimonies from desisters and detranstioners. The final result, 48 pages long, was run past a teacher and a safeguarding lead for a final check. Everything had to be 100% accurate. On top of that, editing and design had to be perfect.

” I needed to show them there was an alternative and a pushback to their expected guidance. There wasn’t much response for a couple of days and then Twitter exploded.”

I wrote about the virulent transactivist response to the guide here on my blog, in ““Ban it! Bin it! Shred it!”

At one point, over fifty copies an hour were being downloaded as a social media war raged over the guidance.

At one point, over fifty copies an hour were being downloaded as a social media war raged over the guidance.

“So pleased,” commented one Twitter user. “I sent the link to my local headteacher. He was grateful and felt it would be very useful. We’re a way out rural area, and I wasn’t sure he’d take me seriously. How wrong I was.”

“This TERF bullshit is not “love and neutrality”. It’s transphobia and child abuse.” fumed another.

Stonewall put out a statement calling the guidance ‘deeply damaging’. Stephanie says she has also seen evidence that Stonewall also wrote to local authorities telling them not to use it.

“My thanks to Stonewall,” says Stephanie. “There was a lot of negative reporting on the guide but- partly thanks to Stonewall- it got a lot of publicity.”

The guidance had a huge impact and gave parents the alternative they needed to take into schools and suggest they ‘have a look at this one’. Measured, factual and sensible, clearly not a religious or bigoted publication, the Transgender Trend resource simply focused on children and safeguarding.

“I know that teachers are using it,” says Stephanie, “and I know that local authorities are recommending it. I have had calls form headteachers asking me for advice. It’s part of what keeps me going, knowing that all over the country the guide is being used.”

Therapy Today

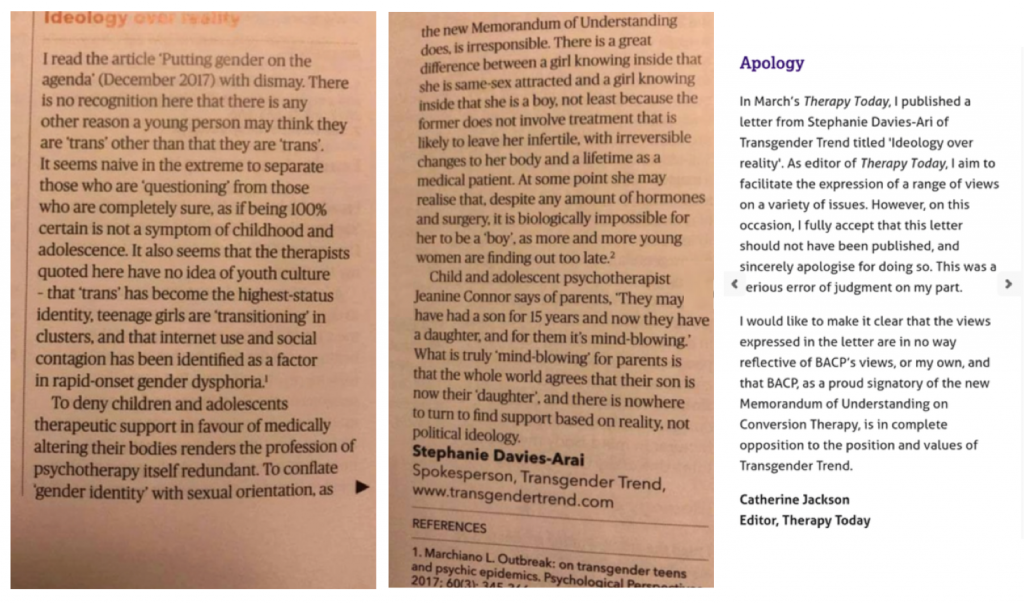

After attending a British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP) conference, Stephanie wrote a letter to Therapy Today praising the conference but raising concerns about the session on gender identity. The letter was published and shortly afterwards the editor, Catherine Jackson, visited Stephanie at her house to interview her for an article they were intending to publish about gender dysphoric children.

“She understood very well,” remembers Stephanie “that I felt that affirmation was a form of gay conversion therapy because most of these kids would grow up to be gay if they were left alone.”

Therapy Today also interviewed James Caspian and Bob Withers. Jackson sent Stephanie the draft article and Stephanie remembers it being a balanced piece with voices from both the affirmation and the watchful waiting or theraputic side. Shortly afterwards Catherine wrote to Stephanie saying because BACP were signatories of the Memorandum of Understanding on Conversion Therapy they’d decided to cut Stephanie, Bob and James from the article. When the article came out it was entirely about affirmation. Stephanie felt so angry that she wrote another letter, which was also published.

“All hell broke loose,” recalls Stephanie. Transactivists called it a ‘transphobic’ letter and a petition was started, full of defamation about Stephanie and Transgender Trend.

“The real targeted harassment started then. They tried to paint me as exploiting parents by charging them; they went to my sculpture website and started saying horrible things about my work and calling me a ‘failed sculptor’. It was really, really personal stuff.”

Stephanie’s letter in Therapy Today & Jackson’s apology for publishing it.

Jackson backtracked and Therapy Today published an apology for printing the letter. When Stephanie wrote asking for a retraction or a right of reply, Therapy Today published the transacitivists’ petition letter in the next issue.

You can read Stephanie’s letter and see a conversation about it here, on Mumsnet.

“They (BACP) threw me to the wolves,” recalls Stephanie. “If I’d taken legal advice at the time, I might actually have sued them for that. It’s totally unacceptable behaviour to encourage bullying. We see this all the time: the bullying women get has been enabled and even encouraged by political parties and institutions. I’m not surprised women turn away from confronting this issue and don’t go there. They’ve seen what happened to JK Rowling. It’s like being put in the stocks! You’re totally exposed because people will believe it.

I really felt I was close to a breakdown then. The impact it had on me was huge – the realisation of how much some people wanted to silence me. But then of course, I got over it and carried on, because basically you’ve got to stand up to bullies. It’s the only way.

In the long run, it didn’t damage me at all. I picked myself up, dusted myself down and started the crowdfunder to pay for printed copies of the schools pack.”

Printed copies of the Schools Resources Pack

‘We wanted to get a pack to every school that has requested one and every parent who has asked for a pack for their child’s school,” explained Stephanie. “We were swamped with requests from all over the country.”

The cost of producing and distributing these packs would run to thousands of pounds, so on 25th May 2018, Transgender Trend launched a fundraiser.

A quarter of the £10,000 total was raised within 48 hours, but transactivists again complained and, on 28th May, the fundraiser was suspended because of claims that the resources promoted hate.

Crowdfunder spoke to Stephanie on the phone and spent six days with their lawyers looking over the schools pack. Nothing hateful or harmful was found and the fundraiser was reinstated. Crowdfunder offered to allow it to run for extra time to cover the lost week but Transgender Trend declined.

I wrote about this in my blog post “Transgender Trend- raising money for resource packs; standing up to bullies.”

The money required was raised and high quality, professionally printed, paper copies were produced.

Copies can be ordered here and parents can arrange to have a copy sent to their child’s school, with or without a covering letter, with an 80% discount, using the code PARENT80.

Constitution

In June 2018, after a brainstorming session at Stephanie’s, the Transgender Trend constitution was developed, clearly laying out the aims and objectives of the organisation. A pdf can be viewed and downloaded here.

In June 2018, after a brainstorming session at Stephanie’s, the Transgender Trend constitution was developed, clearly laying out the aims and objectives of the organisation. A pdf can be viewed and downloaded here.

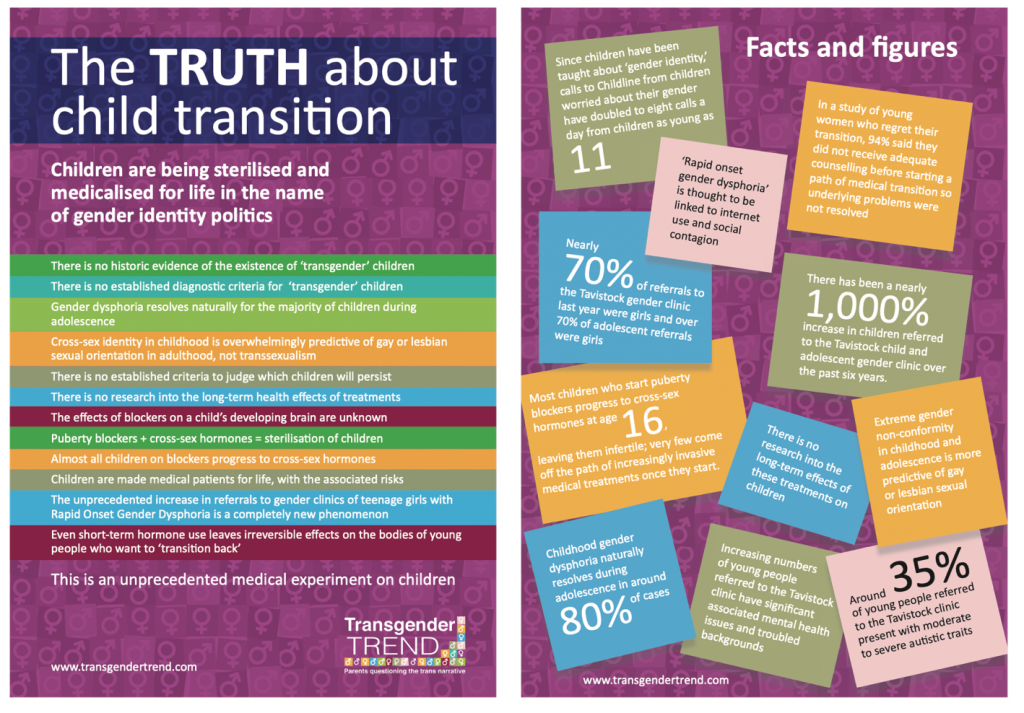

In the same month, the ‘Truth about Child Transition‘ leaflet was produced and distributed. Copies were put in with orders for schools’ packs and they were distributed at events.

The observation that internet use and social contagion were contributing factors in children who developed ROGD was met with the usual unsubstantiated fury by transactivists.

Shortlisted for the Maddox Prize 2018

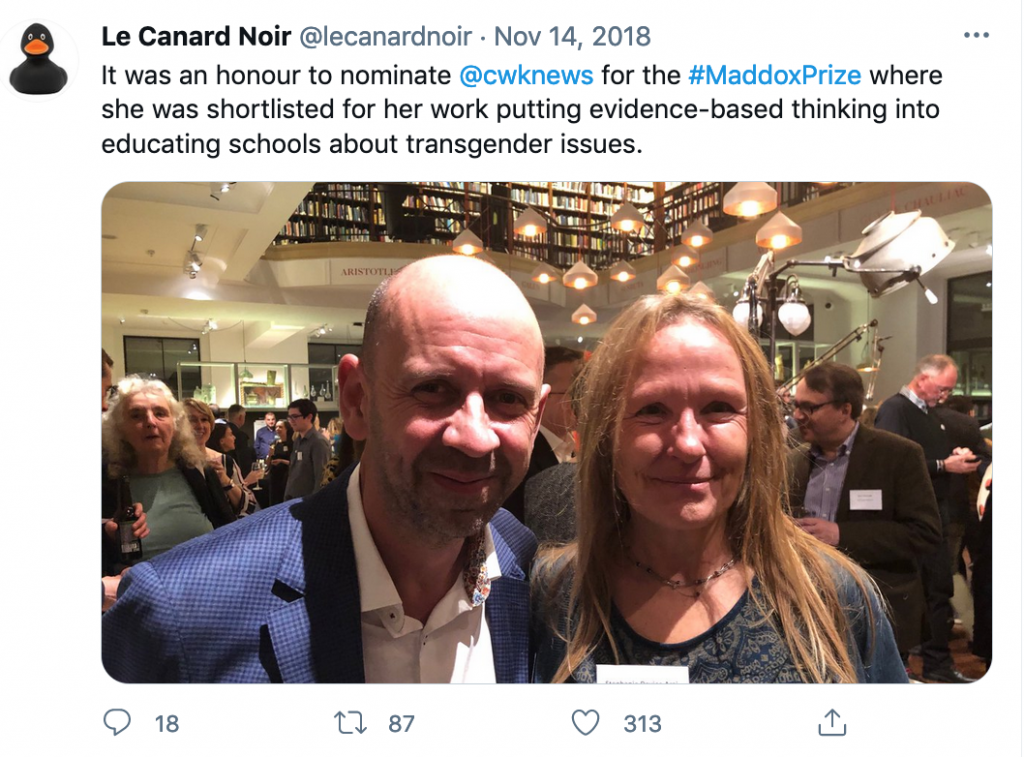

Stephanie was nominated and shortlisted for the Maddox Prize 2018, an award established to recognise “the work of individuals who promote sound science and evidence on a matter of public interest, facing difficulty or hostility in doing so.”

Stephanie was nominated and shortlisted for the Maddox Prize 2018, an award established to recognise “the work of individuals who promote sound science and evidence on a matter of public interest, facing difficulty or hostility in doing so.”

“It was an honour to nominate @cwknewsfor the #MaddoxPrize “ tweeted Andy Lewis, “where she was shortlisted for her work putting evidence-based thinking into educating schools about transgender issues.”

“It was an honour to nominate @cwknewsfor the #MaddoxPrize “ tweeted Andy Lewis, “where she was shortlisted for her work putting evidence-based thinking into educating schools about transgender issues.”

The judges commented on the ‘difficulty of talking about’ the work of Transgender Trend and the challenges in doing so.

Other Writers

Stephanie has had support from several other writers who are regular contributors to the Transgender Trend website, as well as those who have written occasional pieces.

“I’m very proud of the quality of writers I’ve attracted to the site. I see my strength as analysis,” says Stephanie, “joining up dots and analysing data and material, whereas ex-BBC journalist Shelley Charlesworth has a real skill for investigative journalism. She brings another dimension to our work, which is important.”

Visitors to the site can download Shelley’s ‘CAPTURED! The Full Story Behind The Memorandum of Understanding on Conversion Therapy’ here.

Visitors to the site can download Shelley’s ‘CAPTURED! The Full Story Behind The Memorandum of Understanding on Conversion Therapy’ here.

Susan Matthews has written some excellent pieces for the site, which can also be downloaded here under the title ‘The Curious World of Gender Medicine‘.

Susan Matthews has written some excellent pieces for the site, which can also be downloaded here under the title ‘The Curious World of Gender Medicine‘.

Michael Biggs has also written for TGT, most notably the shocking internal report on the effects of puberty blockers after a year (showing there was an increase in will to self-harm and suicide ideation) which was picked up by Newsnight. All Michael’s articles for the website are collated in The Tavistock’s Experimentation with Puberty Blockers.

Michael Biggs has also written for TGT, most notably the shocking internal report on the effects of puberty blockers after a year (showing there was an increase in will to self-harm and suicide ideation) which was picked up by Newsnight. All Michael’s articles for the website are collated in The Tavistock’s Experimentation with Puberty Blockers.

“That was a key moment in revealing information to the public about the effects of puberty blockers,” reflects Stephanie, “because the lobby groups had told us- and continue to tell us- the exact opposite.”

The Transgender Trend shop was added to the website in November 2019. In addition to the above, visitors can also download free copies of ‘Equality Law and Statutory Schools Guidance’, “Stonewall Schools Guidance: A Critical Review’, ‘The Transmission of Transition’ and other free and costed resources.

My Body is Me

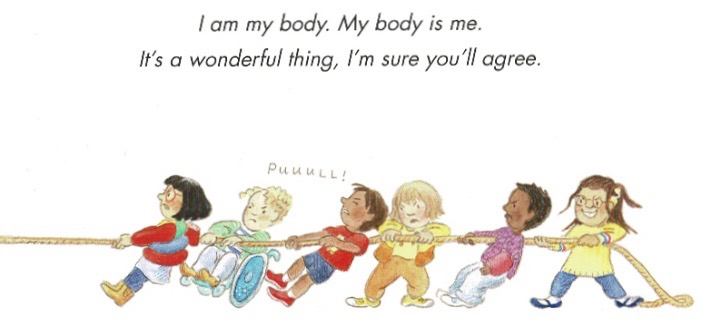

Having produced guides for teachers and schools, Stephanie wanted to produce a book for young children.

Having produced guides for teachers and schools, Stephanie wanted to produce a book for young children.

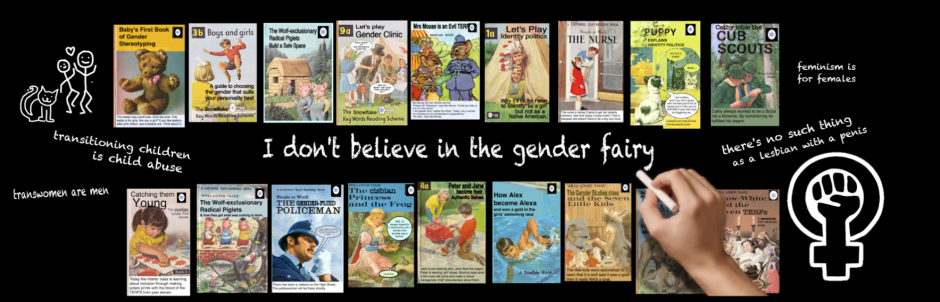

She had counted up the number of transactivist picture books for early years and primary children and found an astonishing thirty eight; confirming a huge push to indoctrinate children with gender ideology. The trans books are promoted as challenging gender stereotypes but of course do quite the opposite, giving children messages such as, ‘ if you love football and skateboarding it might mean you’re a boy’.

Stephanie knew that an alternative book had to not only challenge gender stereotypes but establish that you didn’t need to change your body in order to fit your interests. She got together with illustrator Jessica Ahlberg and they began wondering what sort of storyline they could use.

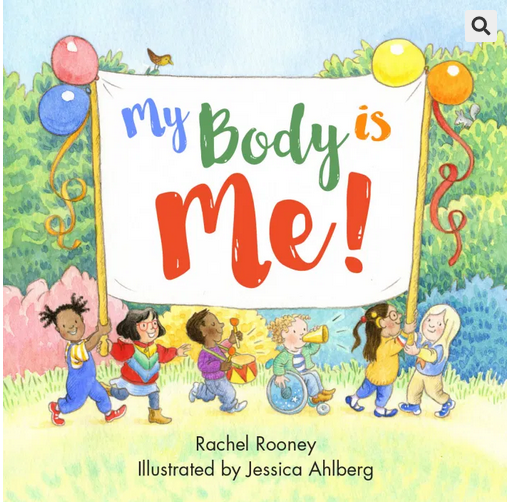

“Then Rachel (Rooney) came along with this perfect poem that said it all,” remembers Stephanie.

It’s a great message for a child, to be proud of what their body can do rather than be concerned with what it looks like. That insecurity in children starts so young these days.”

“The production of resources is really time consuming: there’s so much checking back and forth. And the attention to detail in that book is incredible. The trans books are usually really low quality, so we wanted this to be absolutely perfect. And it is! The illustrations are beautiful and the message of the poem is perfect. We set ourselves several deadlines and were determined to get it out before Christmas 2019- and we did!” Again, I feel so lucky at the quality of people who have been attracted to working with Transgender Trend.”

‘My Body is Me’ is an upbeat, rhyming picture book, aimed for 3-6 year olds. It introduces children to the workings of the human body, and celebrates similarities and differences while challenging sex stereotypes. It also aims to promote a positive self-image and foster self-care skills. The text is inclusive for children with physical or sensory disabilities.”

‘My Body is Me’ is an upbeat, rhyming picture book, aimed for 3-6 year olds. It introduces children to the workings of the human body, and celebrates similarities and differences while challenging sex stereotypes. It also aims to promote a positive self-image and foster self-care skills. The text is inclusive for children with physical or sensory disabilities.”

Predictably- and absurdly- the book was dismissed by transactivists as ‘dangerous’ and ‘hateful’.

Rachel Rooney was subjected to all sorts of online abuse from transactivists for writing ‘My Body is Me’ and the children’s publishing industry enabled it, which Stephanie describes as ‘absolutely shameful’.

Rachel Rooney was subjected to all sorts of online abuse from transactivists for writing ‘My Body is Me’ and the children’s publishing industry enabled it, which Stephanie describes as ‘absolutely shameful’.

The book has been a huge success, with nearly 2,000 copies sold and Rachel posting on Twitter just a few days ago that she had done an online reading for an infants’ school.

On the TGT website, you can hear writer Rooney reading My Body is Me. You can also purchase a copy for £4.99 and download free teachers’ lesson plans and worksheets.

Book contributions

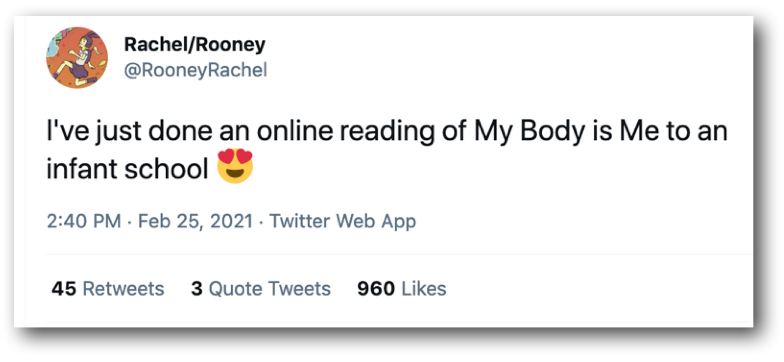

In addition to her own ‘Communicating with Kids’ Stephanie has contributed to several other publications.

‘The Transgender Experiment on Children’ chapter 2 of Moore & Brunskell-Evans’ ‘Transgender Children and Young People – born in your own body‘ (Cambridge Scholars 2018).

‘Gender Identity: The Rise of Ideology in the Treatment and Education of Children and Young People’ (chapter 8) and with Susan Matthews- ‘Queering the Curriculum: Creating Gendered Subjectivity in Resources for Schools’ (chapter 13) of Moore & Brunskell-Evans’ ‘Inventing Transgender Children and Young People’ (Cambridge Scholars 2019)

‘Is ‘affirmation’ an appropriate approach to childhood gender dysphoria?’ was published alongside Toby Young’s ‘Why are so many schoolchildren coming out as trans?‘ in ‘Transgender Children- a discussion‘ (Civitas 2019)

Public speaking

Stephanie has spoken at many events and run workshops on behalf of Transgender Trend, including the following.

In October 2017 she spoke at the ‘Transgender Law Concerns’ meeting in the House of Commons (report here) stating:

“A child’s identity is not fixed: it changes over time, and it is shaped by factors like parental approval and societal influences. If all trusted adults are reinforcing daily a little boy’s belief that he is really a girl, this will have an obvious self-fulfilling effect. Puberty blockers supply the ‘answer’ to the created fear of a puberty he now believes to be the ‘wrong’ one.”

You can find her on YouTube speaking at A Woman’s Place is Speaking Out (Feb 2018) and A Woman’s Place is Speaking the Truth (Sept 2018).

Stephanie at Haringey Resisters

In February 2019 Stephanie spoke at the Haringey ReSisters ‘Gender Identity Teaching in Schools‘ meeting (video here) where she told the audience:

“I shudder to think that if I was growing up today, not only would I be diagnosed with gender dysphoria but I would be judged an extreme case. I would have jumped at the chance to take puberty blockers to stop me developing into something I believed I was not.”

In May 2019 she returned to the Houses of Parliament to speak at ‘First Do No Harm – the Ethics of Transgender Healthcare’ in the House of Lords (report here).

“Labelling children ‘transgender’ politicises the child. Whereas a child with gender dysphoria may be helped and supported, the ‘transgender child’ becomes an emblem of a social jusitice movement and may be used to provide ‘proof’ of an ideology in order to further wider political goals.”

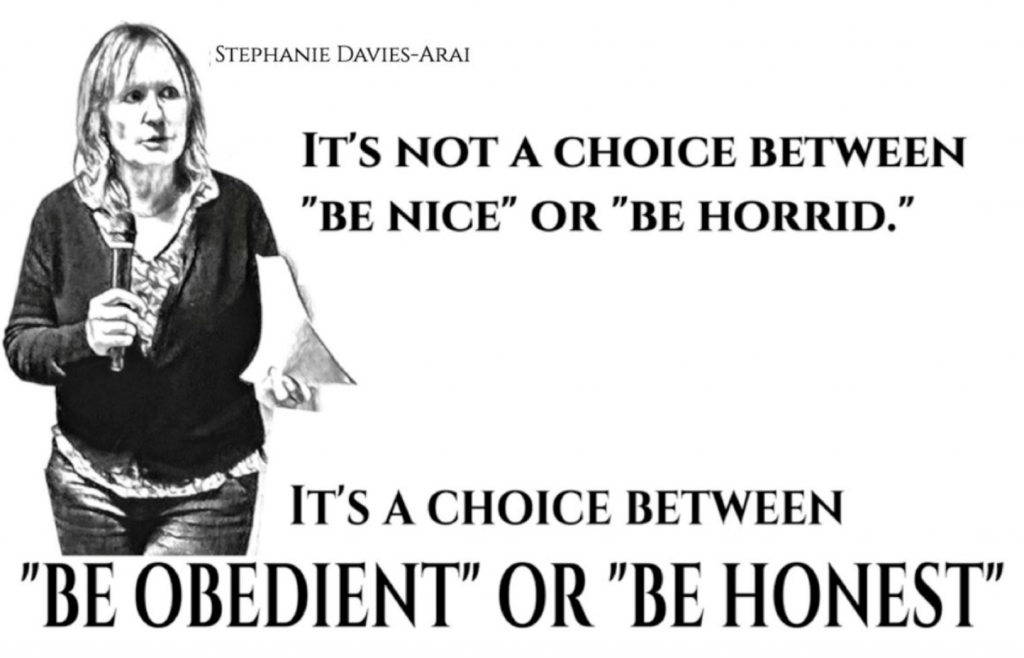

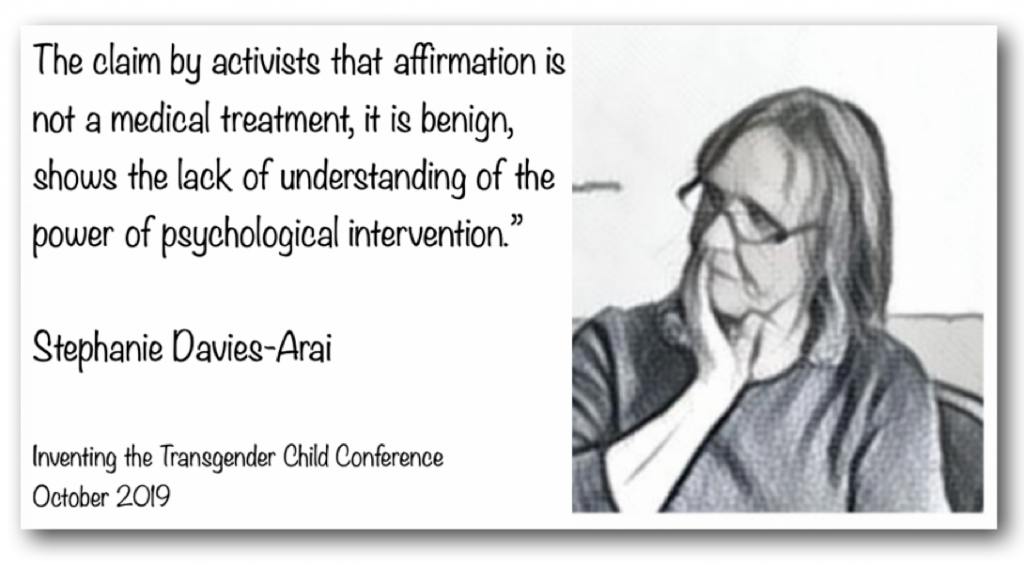

In October 2019, Stephanie spoke to attendees at the Women’s Human Rights Campaign conference, ‘Inventing the Transgender Child’. (video here)

In November 2019 she addressed Hackney Resisters. (video here)

Stephanie at Women’s Lib 2020

The Women’s Lib 2020 conference in London featured a workshop and talk with Stephanie, where she told her audience:

“As women we are brought up to stand outside our bodies and self-objectify… we don’t inhabit those bodies, we are viewers of those bodies along with the culture.

This inevitably creates mental health problems and a split between mind and body.”

Stephanie has given talks at many other group events.

“Honestly, I can’t remember them all,” she tells me, “There have been so many!“

My last Zoom chat with Stephanie for this piece was yesterday afternoon.

“I’ll just grab a quick sandwich and I’m there!” she messaged me.

A ball of energy as ever, she had just finished speaking at the Declaration on Women’s Sexed-based Rights webinar, where she and other panelists had been answering questions about feminism and gender ideology.

@SVPhilimore ran an excellent tweet thread about the event.

Videos & Podcasts

If you’d like to see or hear Stephanie in conversation with others, she has made many appearances in interviews and discussions which are available on YouTube or on podcast. Some are linked to above, and links to a selection of others are below.

YouTube

In May 2019 Stephanie joined Kellie-Jay Minshull for an episode of ‘Posie above the Parapet’. She was interviewed by Kellie-Jay again in May 2020 for an episode of ‘Woman by Definition‘.

In June 2020 she discussed ‘How did this get so far?‘ with Graham Linehan.

In December 2020, Stephanie appeared on Benjamin Boyce’s YouTube Channel, in a discussion called ‘Challenging the Gender Mythos‘.

In February 2021 she was interviewed by Bev Jackson of the LGB Alliance.

Podcasts

In March 2019 Stephanie was interviewed for the Mallen Baker podcast (episode 27) ‘Seeking the Truth without Fear’.

In July 2020, she spoke with Laura Dodsworth on her ‘freethinking’ podcast, in an episode titled ‘Talking Transgender Trend’.

She discusses her work in this FiLia podcast #111, ‘Harms of Gender Identity Teaching, from classroom to clinic’, in October 2020.

Stephanie gives an indepth interview with Julian Vigo in January 2021 on the Savage Minds podcast here.

2020

“So much of my work is behind the scenes,” says Stephanie. “I am constantly working with policy makers and I don’t talk about it much, so it’s work people may be unaware that I do. Transgender Trend, for example, played a part in the new Department of Education Sex and Relationships Guidance.

“So much of my work is behind the scenes,” says Stephanie. “I am constantly working with policy makers and I don’t talk about it much, so it’s work people may be unaware that I do. Transgender Trend, for example, played a part in the new Department of Education Sex and Relationships Guidance.

We were granted permission by the High Court to be Interveners in the Keira Bell case, and of course Stonewall and Mermaids were refused permission.

My experience in the two areas I’ve worked in, health and education, has been hugely valuable in helping achieving my objectives.

For me 2020 was the year of victory on both those sides. I feel that I’ve been engaged in a five year campaign against me and I feel proud that I never responded to the bullying. The results of 2020 have ticked off the initial aims of why I started Transgender Trend: to stop gender identity going into schools and to stop the medicalisation of gender nonconformity. Those were the two primary areas of my concern and I felt like I’ve won. It took a much shorter time that I thought it would. Of course, it wasn’t just me. Lots of other people have done amazing work. Although these are first steps, they are significant steps.

We have a juggernaut to turn round and a lot of damage to undo, but we’re moving forward now and can get on with making positive change.”

I’ve always admired your work. I had a copy of Dykes to Watch Out For in my squat in the late 80s. My family collects graphic novels & comic books: Hot Throbbing Dykes to Watch Out For sits between Castle Waiting and Persepolis on a shelf on my upstairs bookcase. My young adult daughter, a lesbian, has copies of your books strewn around her room.

I’ve always admired your work. I had a copy of Dykes to Watch Out For in my squat in the late 80s. My family collects graphic novels & comic books: Hot Throbbing Dykes to Watch Out For sits between Castle Waiting and Persepolis on a shelf on my upstairs bookcase. My young adult daughter, a lesbian, has copies of your books strewn around her room.

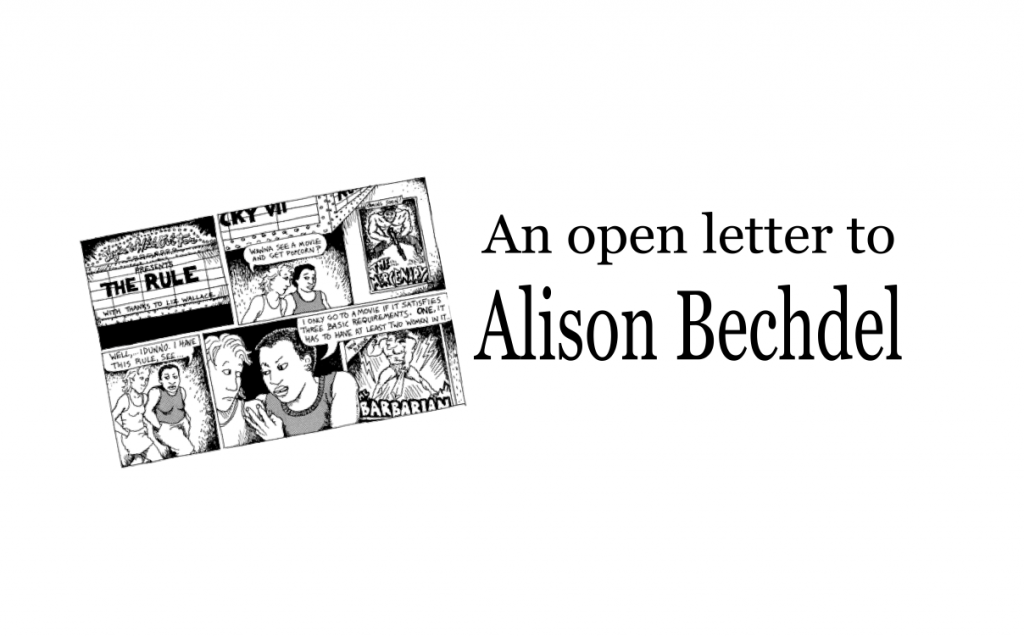

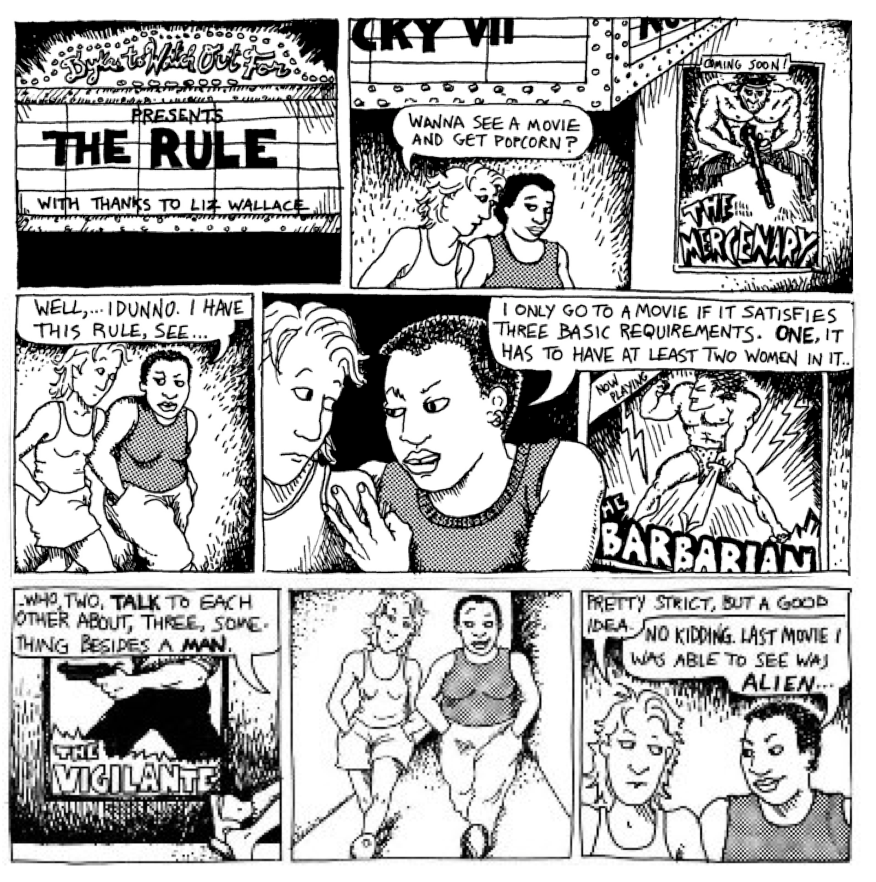

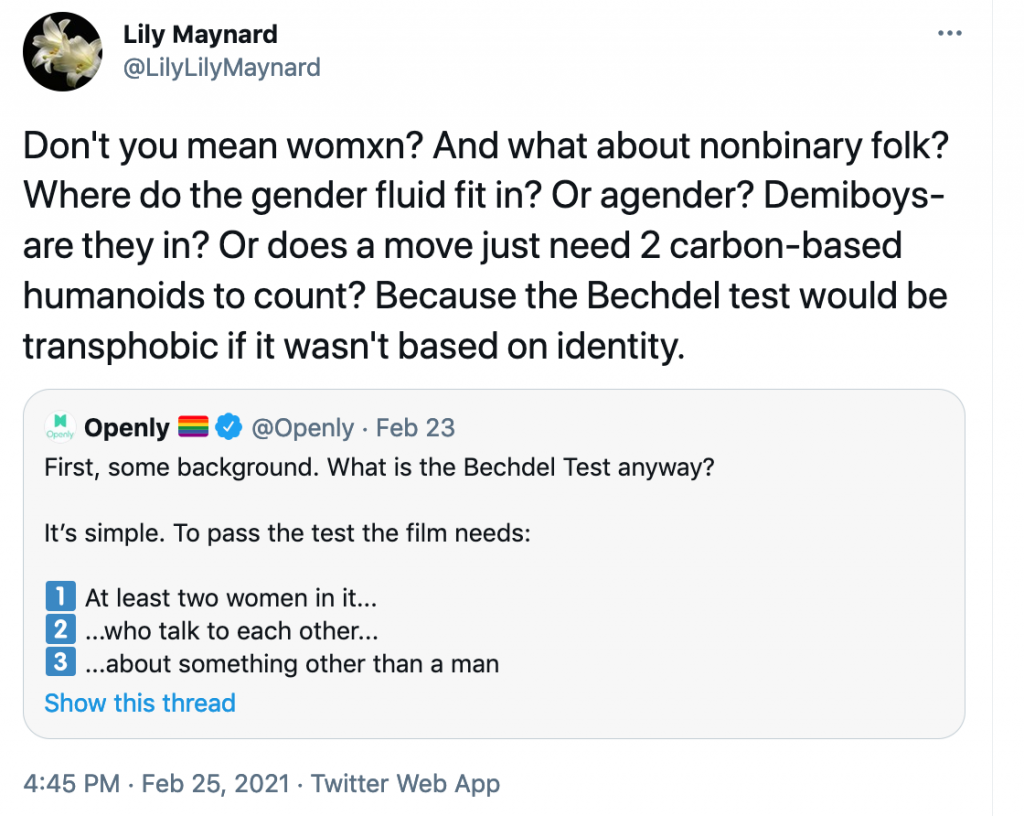

I like to think you knew what a woman was when you drew your iconic cartoon that sets the criteria for what we now call the Bechdel Test.

I like to think you knew what a woman was when you drew your iconic cartoon that sets the criteria for what we now call the Bechdel Test.

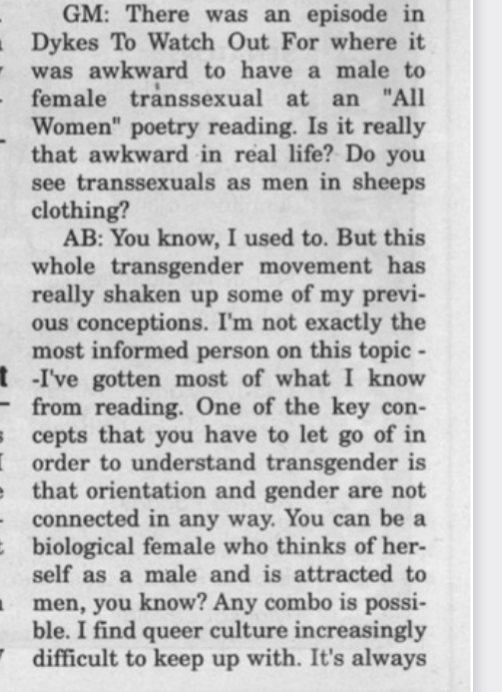

Gender identity ideology changes the Bechdel test. Firstly, it becomes virtually meaningless when it’s claimed that anyone can choose to ‘identify’ into an oppressive situation.

Gender identity ideology changes the Bechdel test. Firstly, it becomes virtually meaningless when it’s claimed that anyone can choose to ‘identify’ into an oppressive situation.