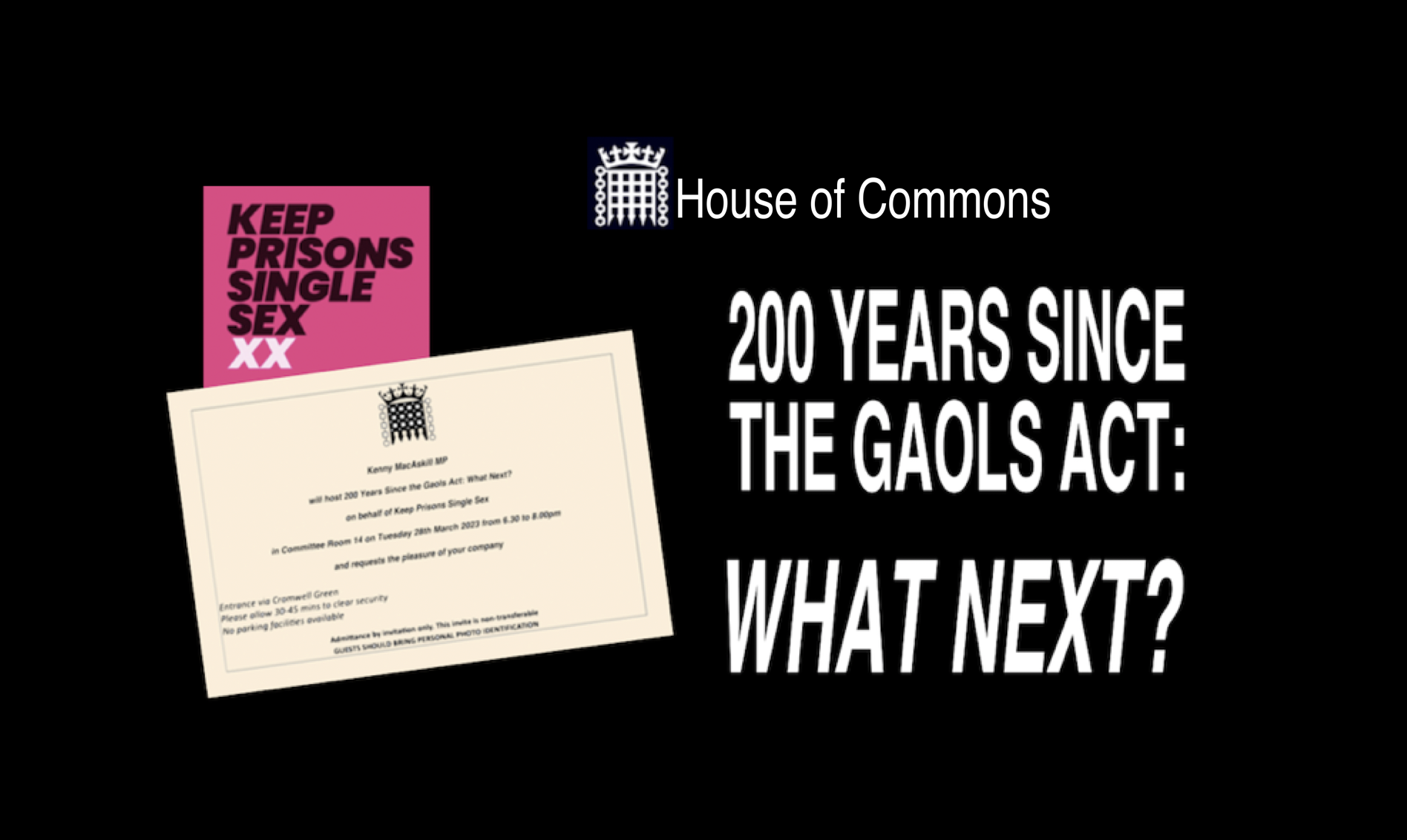

On 28th March 2023, MP Kenny MacAskill hosted an event on behalf of Kate Coleman and Keep Prisons Single Sex. 150 tickets were issued for “200 Years Since the Gaols Act: what next?”

Tickets could be reserved through tickettailor, where the subject matter of the event was described thus:

“In 1823, The Gaols Act passed into law… Amongst its provisions, the Act identified the distinct needs of female offenders and that these should be met through single-sex prison accommodation and same-sex service provision…

Elizabeth Fry, also known as the “Angel of Prisons”, had begun her campaign for prison reform in 1813 following a visit to Newgate Prison. The desperately overcrowded conditions women and children were held in and the sex-based vulnerabilities women in prison experienced appalled her…

Fast forward to the twenty-first century… The unmet needs of female offenders remain of pressing concern. Two hundred years after The Gaols Act, women are not just “marginalised within a system largely designed by men for men”, they and their children are subject to additional sanction.

It’s been 200 years since The Gaols Act – where do we go from here?”

It was late afternoon when we arrived at the security desk for the House of Commons. After staff had loaned me a lanyard and X-rayed my bag I was allowed to proceed through the House, which is a tribute to both art and affluence.

We headed for Committee Room 14, past the rows of marble statues of Very Important Men, with only time to catch glimpses of the numerous, and often vast, paintings that adorned the walls.

Outside Committee Room 14 hangs a painting of a regal-looking woman, Laszio’s study of Lucy Baldwin. Countess Baldwin was, so the plaque nearby tells us, ‘a prominent campaigner for women’s pre-natal care’. She was also instrumental in the passing of the Midwives Act.

Outside Committee Room 14 hangs a painting of a regal-looking woman, Laszio’s study of Lucy Baldwin. Countess Baldwin was, so the plaque nearby tells us, ‘a prominent campaigner for women’s pre-natal care’. She was also instrumental in the passing of the Midwives Act.

I thought of her again later, when Jo Phoenix touched on the tragedies and indignities that have befallen pregnant and birthing women in prison in recent years. It seemed appropriate that a meeting concerned with the rights of women should take place under her scrutiny. I wonder what she would have made of it all.

We passed through the heavy oak door into a high-ceilinged room where we took our seats and waited for everyone to settle. Above the heads of the panel hung a huge and very serious-looking painting entitled Gladstone’s Cabinet. For those who are interested, you can take a virtual tour of Parliament and see many artworks here.

Kate Coleman

Kate opened the meeting by telling us about a Ministry of Justice zoom meeting that she, and other women’s groups, had attended in January 2022, as part of consultation on transgender prison policy. The meeting had left her “depressed, disheartened and fearful for women in prison” after they were told that current policy was ‘working well’ and that staff were happy. No changes were planned.

That meeting came shortly after prison amemdments 214 (violent criminals with a GRC should be housed based on sex) and 97ZA (suggesting a third space) brought by Lord Blencathra were both rejected by the House of Lords.

Feminist groups organised protests and MPs kept up the pressure and eventually the Ministry of Justice listened to those petitioning them, resulting in a policy which states that no male prisoner serving a sentence for any violent or sexual offences, or any prisoner with male genitalia, can be housed ‘in the general population of the female estate’.

“Is this perfect?” asked Kate, rhetorically, “No, absolutely not, and I will not be happy until there are no male prisoners at all in women’s prisons.”

Scottish prisons, however, continue to hold male prisoners convicted of serious violent offence in the female estate.Recently numbers have even increased.

Observing that there is still much work to be done, Kate handed over to Ken MacAskill.

Kenny MacAskill

Kenny said that he had been happy to facilitate a room for Kate to hold this meeting. MacAskill was Justice Secretary of Scotland between 2007 and 2014 and told us that he holds the whole of the UK prison system in ‘the highest of regard’. He observed that not only are those who work with prisoners generally held in lower regard than those who work with children or animals, but that they receive less training.

He refered to a recent story in the Times revealing that half the men in Scottish prisons claiming to be women only decided to do so after their conviction, and that this is clearly because they wish to avoid being held in the male estate.

He refered to a recent story in the Times revealing that half the men in Scottish prisons claiming to be women only decided to do so after their conviction, and that this is clearly because they wish to avoid being held in the male estate.

“Scotland is now far worse in terms of what is happening to vulnerable distressed women.”

Observing that many women in prison have been subject to violence at the hands of men, he emphasised how inappropriate such placement is. Many male prisoners ‘have a propensity for severe violence’ so vulnerable men should also be kept safe – in the male estate.

Joan Smith

Author and journalist Joan Smith chaired the panel. Her books include Misogyny and Home Grown: How Domestic Violence Turns Men Into Terrorists. She was Co-Chair of the Mayor of London’s Violence Against Women and Girls Board from 2013 to 2021

Introducing herself as a journalist, reporter and women’s rights campaigner, Smith told us she had spent much of her career writing about misogyny in the criminal justice system. It was while she was covering the Yorkshire Ripper murders that she first realised how terribly the prison justice system treated women who are victims and witnesses to crime. While writing her book Misogyny, she researched violence against women, concluding that not enough attention is paid to what happens to women and the violence they suffer.

Introducing herself as a journalist, reporter and women’s rights campaigner, Smith told us she had spent much of her career writing about misogyny in the criminal justice system. It was while she was covering the Yorkshire Ripper murders that she first realised how terribly the prison justice system treated women who are victims and witnesses to crime. While writing her book Misogyny, she researched violence against women, concluding that not enough attention is paid to what happens to women and the violence they suffer.

“Vulnerable women, who were probably themselves victims of crime as well as having committed offences, should not be locked up with violent men.”

Smith became involved in the campaign to keep prisoners single sex when the gender recognition reform bill was being discussed in Scotland. As recently as three months ago, she said, we were being told self ID would never be abused and that we were ‘scaremongering and transphobic’. She was shocked that a judge would use ‘preferred pronouns’ in court when the law does not prescribe doing so.

“As a journalist I’m not going to write about these people and pretend I think they’re women when they’re very obviously not.”

She was also shocked by Scottish Prison Policy and the privileges it allowed men in prison who ID as women,for example, wigs and hairpieces, “as if they are going into some sort of Spa treatment’.

Smith observed that men who are jealous of women, or hate women, will behave badly towards women if they get the chance, and that a women’s prison is the ideal environment for them to do so.

Michael Biggs

Michael Biggs is Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Oxford. His article on the ‘Queer Theory and the Transition from Sex to Gender in English Prisons’ was published in the Journal of Controversial Ideas in 2022. He is a director of the human rights organization Sex Matters. You can read a more lengthy biography of each of the speakers here.

Michael had a series of slides to accompany his speech but I couldn’t really see them from where I was sitting. He spoke about the Gaols Act of 1823 which stated that male and female prisoners should be ‘confined in separate buildings or parts of the prison’, adding that the United Nations also advises that men and women should ‘as far as possible be kept in separate institutions’ . If they must be housed together, ‘women must be kept entirely separate’.

Biggs said that recently the idea that there are two sexes, male and female, had begun to give way to gender identity and the way a person feels. Pointing out that the most radical changes concerning this in England had started out under a Tory government, he believes that a change of attitude towards human rights and the influence of queer theory have both played a part.

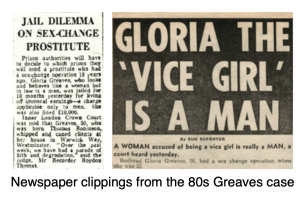

He cited the famous case of Gloria Greaves who was convicted of living off immoral earnings, a charge that could only be levelled at men at the time. Greaves was sent to HMP Holloway, a women’s prison, because he had undergone vaginoplasty. In 1994, in response to questions from Liberal Democrat MPs, it was established that if a man had had surgery, he should be placed in the women’s estate.

He cited the famous case of Gloria Greaves who was convicted of living off immoral earnings, a charge that could only be levelled at men at the time. Greaves was sent to HMP Holloway, a women’s prison, because he had undergone vaginoplasty. In 1994, in response to questions from Liberal Democrat MPs, it was established that if a man had had surgery, he should be placed in the women’s estate.

In 1999 a series of judicial reviews meant that surgery became available to prisoners who were already in prison. Longstanding prisoners could apply to have genital surgery, which would result in a move to the women’s prison.

John Pilley was the first case of a prisoner who had committed violent offences against women being transferred to to the female estate. Sentenced to life for kidnapping, he changed his name to Jane, underwent surgery and was transferred to HMP Holloway. In what Biggs refers to as a ‘bizarre twist’, Pilley then transitioned back into a man, had a phalloplasty and moved back into the male estate.

The law then moved from covering people who had undergone surgery to a definition of ‘legal sex’. The Gender Recognition Act (GRA) was “the first law in the world to divorce changing legal sex from any medical procedures at all”.

Stephen Whittle who was the architect of this law was inspired by Judith Butler and the idea that gender is performative, says Biggs.

In 2001, Mark ‘Karen’ Jones was jailed for killing his boyfriend. On release from prison he tried to rape a female sales assistant in a transexual clothing shop. Back in prison he applied for genital surgery but the Charing Cross clinic wouldn’t consider it until he had ‘lived as a woman’ for a year. Despite the prison psychologist reporting that Jones was ‘narcissistic and sadistic’, it was decided to move him to Holloway so he could ‘live as a woman’.

Prison rules now stated that a male to female transsexual person with a gender recognition certificate could only be refused location in the female estate on security grounds.

Over the next few years Paris Lees, Laverne Cox and Chelsea Manning were given a lot of exposure in the paper as ‘trans’ ex-prisoners. When’ Tara’ Hudson, who had previous convictions for violence, headbutted and serioudsly injured a barman, he was put in a men’s prison because he didn’t have a GRC. A petition to have him moved gained 125,000 signatures in just three days. The case resulted in the first ‘trans protests’ outside the courts in Bristol. Around this time, two trans-identified male prisoners killed themselves while in men’s prisons and the Guardian published an article about the crisis facing transgender women in prison.

The result was that the government launched a review into the care and management of transgender prisoners. Advisers included Jay Stewart of Gendered Intellegence, who said that ‘queer theory was the road map’. Evidently Stewart’s PhD thesis cites Judith Butler 72 times. The review took a lot of evidence from transgender prisoners but none from women. New rules agreed that it was best to ‘allow transgender offenders to experience the system in the gender they identify with’.

The number of transgender prisoners increased from 70 in 2016 to 163 just three years later.

Biggs referred to convicted paedophile David ‘Karen’ White who was placed in a women’s prison under the new system. There he sexually assaulted several women ‘before becoming the face of a campaign by Fair Play for Women’. The prison White was placed in also had a mother and baby unit.

Biggs referred to convicted paedophile David ‘Karen’ White who was placed in a women’s prison under the new system. There he sexually assaulted several women ‘before becoming the face of a campaign by Fair Play for Women’. The prison White was placed in also had a mother and baby unit.

Biggs also mentioned Kyle ‘Kayleigh’ Woods, convicted of murdering his female flatmate and later moved to a women’s prison, where he had sex with at least one prisoner. Around this time there were at least five other records of sexual assaults by transgender inmates, against women in the women’s estate. It became public knowledge that 48% of transgender prisoners had been convicted for sex offences. In the general male prison population it is 19%. The percentage of women imprisoned for sexual offences is just 4%.

“So there was a reversal of public opinion at this point.”

A judicial review was brought by a woman who had been in a prison with a transgender male and in that case the judge rejected the idea that women were ‘required to be a kind of audience for the performance of gender’.

Biggs concluded by emphasising that we don’t know what will happen next and the importance of groups such as Keep Prisons Single Sex, Fair Play for Women and Sex Matters which keep a close eye on this issue.

Ian Acheson

Acheson is a former prison governor with extensive involvement in operational command of serious prison incidents and counter-terrorism policy and practice. He used to be Chief Operating Officer for the Equality and Human Rights Commission. You can read a more lengthy biography of each of the speakers here.

He began by saying how privileged he felt to be on this platform, particularly with Kate Coleman who had stood up so bravely to ‘‘the moral and ethical travesty of having men in women’s prisons’. This was met with much applause and Acheson paused while it died down.

Institutional capture, he said, refers to state agencies being‘infiltrated and changed by new doctrines and forms of activism that fundamentally alter their operation in some specific way’.

In the late 1990s he had worked in Durham on the country’s only female high security unit. It housed ‘exceptionally dangerous women including terrorists’. It was ‘a claustrophobic atmosphere saturated in risk but it was also saturated in distress’ as many of the women had themselves suffered trauma.

He said the idea of locking those women up with trans-identifed men would have seemed ‘mediaeval back in the mid 90s’ yet now we are told it is progressive and those who object are bigots. Elizabeth Fry, he said, would be horrified. Acheson described it as ‘nothing less than state sanctioned trauma’.

UK prison services have claimed they are merely the instruments of their respective legislatures trying to enact the law in relation to a particular interpretation of the GRA and the Equality Act. This is not good enough.

Acheson described three characteristics of an organisation that had been institutionally captured.

ISOLATION

The prison and probation service does the majority of its business ‘behind high walls and locked doors’ . Unlike the police and fire fighters, their leaders are almost invisible to the public, yet it is is a ‘law enforcement agent of national and societal significance’ with 50,000 people working across 104 prisons. A recent FOI request showed HMP Bellmont to be ‘awash with serious violence’ much of it against staff. Bad ideas and practises flourish in isolated institutions.

INSULARITY

Many people involved in the prison service have only ever worked for the prison service. There’s ‘a distinct lack of external influence’ and many criminal justice charities are staffed by people who have left the prison service and end up ‘petitioning their former employer for reform with a pretty poor record of success’. To applause, he acknowledged that Richard Garside was there to prove the exception to that rule.

Training for prison managers who reach Petty France puts emphasis on prison managers’ main task being to ‘ameliorate the pains of incarceration’. Acheson cites the influence of Foucault who looked on prisons as ‘inherently bad and the gaolers not much better’, a lens through which prisoners are seen as primarily victims and prison managers as instruments of social justice. This can go badly wrong, as shown by the inquest into the killings by Usman Khan in 2019. Khan was encouraged to join a ‘nonvalidated’ study group called ‘Learning Together‘ where he performed impressively. Acheson suggests that the ‘fairy dust of Learning Together’ blinded the prison authorities to his ‘continuing and increasing dangerousness’ which ended with him stabbing two young students to death after an event which ‘with intense grotesque irony’ was intended to celebrate rehabilitation.

Insularity imakes it difficult for managers to object to ‘daft and dangerous ideas’ without risking their own jobs.

INSTITUTIONAL CAPTURE

Senior managers in the prison service are rarely removed for incompetence, Acheson states, more likely they are ‘moved sideways if not upwards’. The Governor of HMP Whitemoor was promoted shortly after the events described above. Corporate leadership doesn’t understand the day to day running of prisons and poorly trained officers are ‘thrown into institutions teeming with distress and brutality’. There is poor accountability and little scrutiny in a system ‘addicted to cheap custody’.

Of the proposals that lead to dangerous men being housed in women’s prisons, Acheson observes ‘issue of risk in this area should have been glowing red for years.”

‘Luxury progressive beliefs’ will not fix a system where in some prisons it is ‘easier to get crack than clean sheets’ and it is easier to focus on ‘imagined microaggressions’ rather than deal with the ‘societal macro aggression that 53.9% of released prisoners are reconvicted having served sentences of 12 months or less.”

The ‘soaring rates of distress’ in women’s prisons are reflected in recently gathered data suggesting that self-harm has increased in women’s prisons by 42%.

Protecting women in prison does not automatically mean neglecting trans-identified offenders. Acheson suggests a dedicated risk unit for ‘male to female trans prisoners’ within a male prison. Such a unit would stop ‘opportunistic manipulation’.

This recommendation was met with much cheering and applause.

The creation of such a unit is well overdue, he concluded, and it should be possible to achieve within existing legislation. It should have been created before we reached the current situation where we are ‘struggling to repair regressive policies which put women at risk’.

Lord Blencathra

Joan Smith thanked Ian Acherson and introduced the next speaker, Lord Blencathra, who has been a Conservative peer since 2011. He was formerly Minister of State at the Home Office and Chief Whip. You can read a more lengthy biography of each of the speakers here.

Smith commended the work he had done within the House of Lords to support women and girls, observing that there are many peers willing to say things that nobody will say in the House of Commons.

Ldord Blencathra said he was “delighted to see so many people here for this important event”.

He reminded us that when the 1823 Gaols’s Act was passed, it banned manacles and provided prisoners with regular religious visits, hygiene and education. It was meant to set standards across all prisons in England and Wales and paid especial attention to the circumstances of female prisoners. It identified the sex-based needs of female offenders and said there should be same-sex service provision and single-sex prisons. Female prisoners should be attended by female officers. He said he recognised that this act was the result of campaigning by women for women, noting that Elizabeth Fry wrote in her diaries about the problem of rape and sexual exploitation when male and female prisoners are held together, and campagnied for these reforms for a decade before they became law.

Blencathra called women in prison ‘the most vulnerable, overlooked and powerless within society’ and observed that women in prison, like all women and girls, are entitled to single sex spaces for reasons of privacy, dignity and safety.

Over 40 years in in parliament, he had never felt the need to speak up for women and girls before, because he felt that women’s rights were improving. But around 2020 he began seeing that women’s rights were being eroded and “even the word woman was being obliterated from the language”. He expected female parliamentarians to fight about this but observed, “that did not really happen”.

Kate Coleman then persuaded him to ‘ask a question or two’ about men being placed in women’s units. He was ‘appalled’ at the answers he got and horrified that the Tory government he supported, ‘which should have more sense,’ was ‘eradicating the rights of biological women‘ in this way.

So at the beginning of 2022 he brought amemdments 214 (violent criminals with a GRC should be housed based on sex) and 97ZA (suggesting a third space).

So at the beginning of 2022 he brought amemdments 214 (violent criminals with a GRC should be housed based on sex) and 97ZA (suggesting a third space).

“I was supported in this by colleagues across the political spectrum,” he told us, “although not very many of them.”

They did not expect the amendments to be passed but they did it anyway, to get the matter discussed and ‘so for three hours the attention was on women in prison’.

Blencathra doesn’t see it as a defeat because the amendments were part of the ‘important progression of activity’ that has led to the revised Ministry of Justice policy ‘which provides far greater protection for women in prison’.

Emphasising the importance of sex, Blencathra observed that women are slowly regaining their power, mentioning JK Rowling, Maya Forstater and Bev Jackson among others, concluding “and of course our own absolutely magnificent Dr Kate Coleman!”

Whoops and cheers from the audience.

They give courage to us all, he said, observing that this is a feminist struggle but it’s also one that should concern all ‘right-minded’ people.

Lord Blencathra concluded, “Where women have been terrified of speaking up there is a duty of men to speak up, including old gits like me, and I’m proud to continue to be such a man with Kate’s encouragement.”

Jo Phoenix

Jo Phoenix is an author and Professor of Criminology in the School of Law at the University of Reading. She has written extensively about sex, gender, sexualities and justice and a trustee at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies. You can read a more lengthy biography of each of the speakers here.

Jo thanked Kate for inviting her and observed that even as little as two years ago it was impossible to discuss this subject, referring to an event in 2019 where she tried to ‘talk about these things’ at the university of Essex but was cancelled and blacklisted.

Phoenix believes we should apply single-sex exemptions to female prisons ‘and not just in terms of prisoners’. Men do not belong in women’s prisons, however they identify. Research tells us that sending people to prison is ‘a bit of a failure as far as managing levels of crime goes’. There is no relationship between the rates of incarceration and the amount of crime in society, holding that most crime stems from governments which do not address social welfare problems and that women are especially affected by class and sex-based inequalities. The state does not uphold its responsibility for childcare, housing, welfare,and other issues that affect women. Many women have their lives torn apart by male violence and sexual abuse and, for some women, these factors can combine to create a cycle of alcohol and drug addiction, and lawbreaking.

Outside of prison, we can take steps to improve our safety: we can leave a room for example. Prisons exist to deprive an individual of their liberty, and in that situation sex matters more than ever.

“The universal and most all-encompassing difference between people is sex.”

She spoke of imprisoned women as being ‘double damned and doubly deviant’, as they are seen to have failed not only as good citizens, but as women. More women than men are in prison for short sentences. Jo reeled off quite a list of shocking statistics, here are the ones I caught.

60% of women in prison have children and 95% of children of incarcerated women have to leave the family home. Nine out of 10 female remand prisoners don’t end up in custody. 49% of women in prison are diagnosed with anxiety or depression (compared to 19% of the general female population). 90% of women in prison have suffered significant head injuries at the hands of men.

60% of women in prison have children and 95% of children of incarcerated women have to leave the family home. Nine out of 10 female remand prisoners don’t end up in custody. 49% of women in prison are diagnosed with anxiety or depression (compared to 19% of the general female population). 90% of women in prison have suffered significant head injuries at the hands of men.

Women who have been victims of sexual or physical abuse should be informed of their right to prosecute their attacker, and their doing so should be facilitated.

Women in prison give birth and lactate, they menstruate and go through menopause. Their biological needs are different to those of men. She reminded us of recent stories of stillborn babies being born in prison and recollected hearing stories of women in childbirth being shackled to their beds.

“Women deserve conditions that address their unique needs as women… I say this not because I have anything against transgender prisoners who have their own unique needs”.

Jo, who was the last speaker, finished to much applause.

The chair said she wanted to thank all the speakers but unfortunately there wasn’t time for a Q&A ‘because they’re quite strict on kicking us out’.

Kate concluded by saying that she’s aware she sometimes comes under criticism for not getting involved in other areas that the criminal justice system affects women. Her goal is to be able to move on to other things but there is still a lot of work to do in this area first, including data collection throughout the criminal justice system.

“The work has to continue, so thank you so much to everybody, and goodnight!”