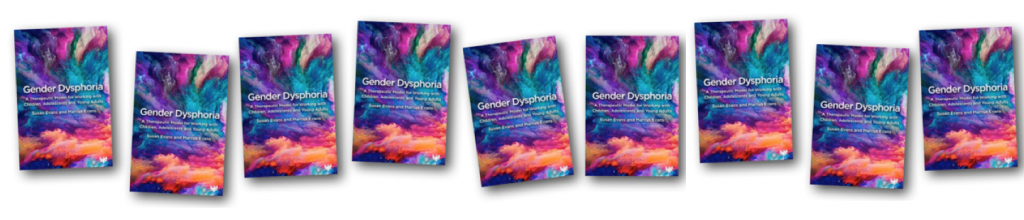

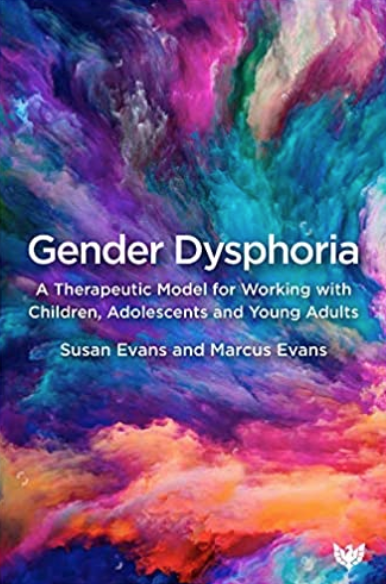

In May 2021, Susan and Marcus Evans book, , was published by Phoenix Press.

The authors discuss the developmental and relationship issues that can cause a child or young person to become trans-identified and some of the ways a therapist can help them to explore the reasons behind those feelings.

What I have written here is my interpretation of the Evanses work: the conclusions I reach may well not be the same as the ones you will reach when you read their book for yourself.

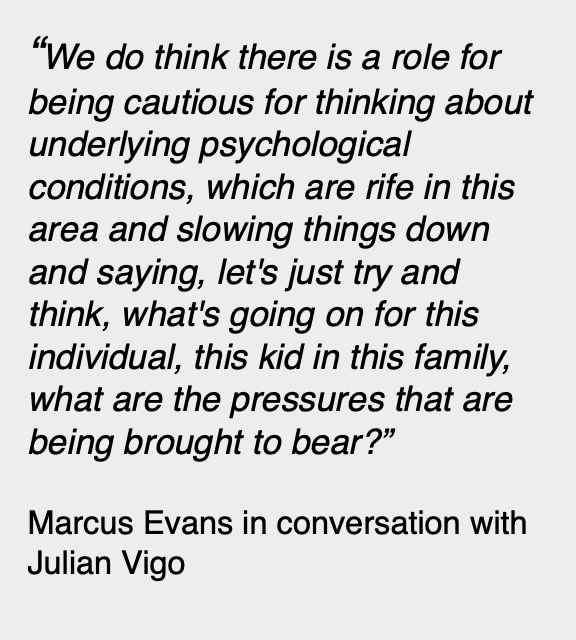

Occasionally I’ve included a short block quote from Susan & Marcus’ discussion of the book with Julian Vigo on a Savage Minds podcast.

Sue Evans is a psychoanalytic psychotherapist and Marcus is a psychoanalyst. No, I’m not entirely sure what the difference is either but they have almost a whopping eighty years experience in in a variety of NHS services between them.

Susan used to work for the GIDS (Gender Identity Service for children) and Marcus spent many years as clinical lead of the Adult and Adolescent Department at the Tavistock & Portman. Susan now has a private practice in South London. Marcus is the author of the catchily named Making Room for Madness in Mental Health and Psychoanalytic Thinking in Mental Health Settings. There is little doubt that they both Know Their Stuff.

The book has a startlingly psychedelic cover which is quite fitting as the content is, well… pretty mind blowing in some ways. After reading it I was left wondering how the affirmation model could ever have become the norm for dealing with gender dysphoric children.

It starts with a preface by David Bell, who observes that we know little behind the reasons for the exponential increase in young people presenting with gender dysphoria, and suggests that, as well of being of interest to clinicians, the book will also “be of considerable interest to those who, whilst not directly involved in working with people suffering with gender dysphoria, seek to understand it in depth.”

The foreword, by Stephen B Levine, discusses the lack of agreement about the best way to proceed when dealing with the gender dysphoric patient, the passion of the culture wars, science versus advocacy, and observes that two important hypothesis should be considered:

Firstly, that a trans identity “represents a symbol of an underlying developmental process” and secondly that it “creates a new worrisome symptomatic relationship to the self, to others and to the tasks of development.”

Levine suggests keeping ten questions in mind while reading the book, including the following:

“Can one be born into the wrong sex?’

“Does affirmation prevent suicide?”

“What is known about the outcome of psychotherapies for trans-identified young people and adolescents?”

Part 1 – The Social Context

The book goes remarkably well with my tablecloth and plates.

The first two chapters are where the Evanses “outline our rationale for writing the book”.

Chapter One explains how Susan’s concern about the ease with which children were receiving hormone treatments at the Tavistock, and its reluctance to discuss this with her, resulted in her ‘whistleblowing’.

A resulting report made recommendations for change but the changes were not implemented and Susan resigned from the clinic.

Sue told me:

“I had raised concerns when I was a staff member of GIDS between 2003-6, about aspects of the clinical care. The Tavistock’s approach, to ignore the parents’ letter of concerns (2018) and the concerns of whistle blowing staff, made me realise that there needed to be a more serious investigation into the care of gender incongruent children, hence the Judicial review. We decided to write the book in order to contribute to the thinking in this area and to ensure that there is curiosity about the presentation and lives of these children.”

Marcus, a Tavistock Trust governor, also had concerns about the letter sent by parents and about David Bell’s report which dealt with whistleblowing staff. In 2019 he resigned.

Marcus told me: “I resigned as Governor of the Tavistock Board because I did not believe that the Senior Management were prepared to address the concerns raised by several of the GIDS clinical staff and also the parents of children in the service.”

In the same year Marcus gave a talk at the ‘First Do No Harm’ event at the House of Lords. I was present and wrote about the event on my blog: you can read my report here. In casual talks after the meeting, there was general agreement by attendees that young children could not consent to such treatments.

One of those present was ‘Mrs A’, mother of a 15 year old autistic girl. Susan and Mrs A agreed to request a judicial review on the issue of informed consent: Susan stepped down once detransitioner Keira Bell became involved. This judicial review took place in October 2020, resulting in the decision that a ‘best interest’ order must be made by a court before children under sixteen could be prescribed puberty blockers. NHS England complied.

Events surrounding the judicial review left the Evanses ‘acutely aware’ that “children, their families and clinical services (would) need alternative models of treatment.”

The book is a response to that and the authors hope it will help ‘parents, teachers, social workers and other healthcare staff… counsellors, paediatricians, paediatric psychiatrists, GPs, youth workers, charity workers and policy makers.’

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

The Evanses emphasise that their model is ‘neither pro nor anti transition’ and that they understand that some adults may need to transition in order to lead comfortable lives. As such they believe that adults could also benefit from this book as it may help to ‘explore their defences and internal psychic conflicts’.

The Evanses see trans-identification as likely to be a defence against past psychological trauma, both external and internal. They suggest that the trans-identified young person has “a mind at odds with the physically sexed body” noting that many of them “have complex needs with co-morbid problems such as autism, histories of abuse or trauma, social phobias, depression, eating disorders and other mental health symptoms”. Because of this, a thorough assessment of all areas of the young person’s life is necessary. They believe that such work will benefit a young person whether or not they go on to transition.

Chapter 2

Chapter 2

Chapter two deals with “the societal, cultural and political trends and their effects on the clinic environment”. Contemplating the global political capture of gender ideology they observe that the clinical challenges remain unchanged. Noting that numbers of referrals to the NHS gender clinic have increased from 100 in 2005 to over 2,500 a year, they observe that girls are now presenting in far greater numbers than boys.

Despite this unexplained and unexamined shift, the model of affirmation has replaced the ‘more conservative and largely less physically harmful’ model of watchful waiting. Research is emerging that suggests the affirmation model may consolidate a young person’s trans identity.

The Memorandum of Understanding on Conversion Therapy implies that everyone has a gender identity, “akin to a religious soul that one may discover and nurture,” suggest the Evanses. Whilst appreciating that a therapist should not project their own ideas of ‘normality’ onto a patient, they are critical of the ‘affirming cheerleader’ role taken on by many dealing with young people, pointing out that “we do not simply accept the anorexic’s belief that they are overweight and respect their wish to starve themselves.” Instead, a good therapist will aim to understand what drives that belief.

Social media has a large role to play, they suggest, and transgender websites ‘tend to be echo chambers of positivity’. While finding them can feel like a relief for gender dysphoric young people, who may feel they are being offered a new place to belong or provided with a new tribe or family, the Evanses are concerned about the power of social contagion via the internet and point out that some have described the trans community as a cult.

Social media has a large role to play, they suggest, and transgender websites ‘tend to be echo chambers of positivity’. While finding them can feel like a relief for gender dysphoric young people, who may feel they are being offered a new place to belong or provided with a new tribe or family, the Evanses are concerned about the power of social contagion via the internet and point out that some have described the trans community as a cult.

Society’s refusal to explore this causes cognitive dissonance as many individuals are compelled to ‘close their minds to the reality of biological sex’.

In a section subtitled ‘Homosexuality, misogyny and feminism’ they discuss ROGD, the ultra-feminisation of many celebrities and the paradox of queer politics whereby gender non-conformity and stereotypes have been appropriated by the trans movement. They observe that transition may be seen by some young people as a ‘cure’ for their homosexuality at a time when the frontal lobe of the brain is not yet fully developed and they may be struggling with their own internalised homophobia. Transition is unlikely to be a long-term solution for such young people.

At this point, Freud raises his head, as they discuss envy and rivalry within family dynamics, asserting that ‘we believe unconscious envy has a part to play in the psychology of some trans-identities’.

At this point, Freud raises his head, as they discuss envy and rivalry within family dynamics, asserting that ‘we believe unconscious envy has a part to play in the psychology of some trans-identities’.

Freud pretty much sticks around for the rest of the book.

I asked Marcus to throw some light on this for me, asking,“Would you describe your approach as Freudian?”

He told me:

“I would describe it as a psychoanalytic approach… obviously Freud was the lead on psychoanalysis but there are several theories explored (in the book). A psychoanalytic approach can throw light on the unconscious forces in the mind that lie behind the presentation of gender dysphoria. A thorough examination of the individual and the psychological influences and defences that motivate them can prepare the individual for their future life, whatever decisions they make in relation to gender transition. This exploration needs to take place in a supportive therapeutic environment with the therapist adopting a position of neutrality and curiosity. In our experience, we think that all children and where appropriate their families, should go through a period of thorough, in depth therapeutic exploration before embarking on any concrete medical interventions. Children are often seduced by the attraction of concrete solutions to psychological problems. These short term solutions often have hidden long terms costs.”

Dysphoric feelings about the body stem from the mind but this is often denied by those with a trans-identity. In 2015 the diagnosis of ‘gender identity disorder’ was changed to ‘gender dysphoria’ with the aim of reducing stigma. The Evanses believe that one of the dangers of this is that it runs the risk of perpetuating the stigma associated with mental illness.

Dysphoric feelings about the body stem from the mind but this is often denied by those with a trans-identity. In 2015 the diagnosis of ‘gender identity disorder’ was changed to ‘gender dysphoria’ with the aim of reducing stigma. The Evanses believe that one of the dangers of this is that it runs the risk of perpetuating the stigma associated with mental illness.

“Psychiatry and mental health work is something of a fashion business,” they note, wryly, and “a new age can be defined by its novel mental disorders.”

‘The body is often used to act out something that cannot be accepted or processed by the mind’ they observe, and patients often see physical treatments as a solution to psychic pain.

This chapter also deals with the pressure put on the professional. Many young people present with a script, as if they have learned what to say, often advised by the internet. Some parents push hard for transition which also puts pressure on clinicians. Detransitioners often say they wish professionals had ‘stood up to them’ more and made them explore themselves for longer.

The writers speculate on how doctors who have taken an oath of ‘do no harm’ can manage to justify prescribing medication for young people, observing that many medics may be drawn to this area of practice by a conscious or unconscious enactment of the phantasy/fantasy of their own omnipotence.

The writers speculate on how doctors who have taken an oath of ‘do no harm’ can manage to justify prescribing medication for young people, observing that many medics may be drawn to this area of practice by a conscious or unconscious enactment of the phantasy/fantasy of their own omnipotence.

Susan and Marcus are adamant that the current climate is “very likely a medical disaster in the making”.

This is a fascinating chapter, dealing as it does with the workings of the mind and how we deal with stress and trauma. I also learned the difference between phantasy (an unconscious set of beliefs) and fantasy (conscious thoughts and daydreams) and how the two mix and mingle. There is a short glossary of terms at the back of the book, and Freud’s structural theory of the mind is explained.

I did find some phrases, such as ‘their discomfort in the gender of their natal body,’ to be awkward when referring to a person’s feelings about their sex. I’m unsure why the writers chose not to be clear when they can obviously see the difference between sex (a biological fact) and gender (a social construct).

Chapter 3

Chapter 3

Chapter three looks at the experience of two detransitioners. It is here that we see the first case studies, which give a fascinating insight into the minds of both patient and therapist. I have always had a rather cynical approach to the idea of therapy, which is a very British position: my American friends in the 90s almost all had therapists and many was the conversation that started “My therapist says…”. Perhaps we could all benefit from more supported self-perusal. Certainly while reading the book I found myself more drawn to the idea than usual.

The first case study is that of twenty-five-year-old Bianca who had taken puberty blockers at sixteen, cross-sex hormones at eighteen and had a double mastectomy at twenty. She told the therapist she thought ‘the whole thing was a mistake’. Bianca had talked to her doctor about her feelings of depression and anxiety, but when she mentioned gender dysphoria the doctor had immediately referred her to specialist gender services. Her online friends told her what to say at appointments.

“It was like being coached in a football team,” she told the therapist. “I felt they cared about me.”

The case study deals with two consultations and chronologues part of each consultation and an analysis of what took place.

(In 1989 when I had my first computer, long before I even knew the internet existed, I had a program called Eliza. I thought Eliza was astonishingly clever. It was a therapist program, developed in the 60s, using a person-centred approach. Whilst their methods are obviously far more complex and nuanced than Eliza, the psychological approach adopted by the therapists in these case studies reminded me a little of ‘her’. You can chat to Eliza here.)

(In 1989 when I had my first computer, long before I even knew the internet existed, I had a program called Eliza. I thought Eliza was astonishingly clever. It was a therapist program, developed in the 60s, using a person-centred approach. Whilst their methods are obviously far more complex and nuanced than Eliza, the psychological approach adopted by the therapists in these case studies reminded me a little of ‘her’. You can chat to Eliza here.)

The second study deals with twenty-two year old Emily, a detransitioner who wanted to understand why she had felt driven to transition in the first place. Emily had also spent a great deal of time online, where her new friends had encouraged her to believe that her problems would be be resolved once she had transitioned.

“Any time I felt unhappy, depressed or anxious about myself I would think it was because I hadn’t gone far enough along the process to transition and that I needed to press ahead to the next stage,” she told the therapist.

Part 2 – Development and Gender Dysphoria

Chapter 4

Chapter 4

Early development in the context of the family

Part two considers the child within the family relationship. The Evanses are critical of ‘helicopter’ and ‘snowplough’ parenting techniques, observing that each developmental stage brings its own challenges and whilst parents need to support their children they must also show confidence in their child’s ability to cope with these challenges. The degrees of separation involved in each stages can bring different problems. A child may feel they might be loved more if they were a different person, or imagine a ‘new self’ to replace the one they believe to be inadequate.

“It may also lead to a development of a phantasy of the death of the self and the rebirth of a new self.”

They discuss the case of Sarah, who wished to transition and change her name to Steve. Sarah, who was volatile at home, had discovered pro-ana forums online and developed anorexia. Once this seemed to be under control she became gender dysphoric. Her parents felt she was being rushed into transition by child and adolescent services.

They discuss the case of Sarah, who wished to transition and change her name to Steve. Sarah, who was volatile at home, had discovered pro-ana forums online and developed anorexia. Once this seemed to be under control she became gender dysphoric. Her parents felt she was being rushed into transition by child and adolescent services.

“… as with the anorexic patient, the young person who wishes to transition has transferred the psychic conflict into the body which then becomes the thing they wish to control… the wish to control the sexual development and function of the body is extremely important in both gender dysphoria and anorexia.”

The writers offer some interesting reasons as to why parents might support the transition of their child. The parents’ own homophobia is one possibility, as may be the wish that they had had a child of the opposite sex. Munchausens by proxy may be involved, separation anxiety, or simply the anguish at seeing their child in deep distress and hoping for a quick and easy resolution.

It is importance, they observe, that the therapist is able to show the young person empathy whilst avoiding collusion.

In this chapter the authors write that the child may believe all their problems will be solved if they “are helped to transition to another gender”. This is in contrast to the prior, more sensibly phrased, “physically sexed body” and more reminiscent of the phrase “natally gendered body” used earlier. It is a shame that a consistent approach to language hasn’t been adopted: while it may be reflecting the language used by the young person it is partly the inability to be clear about the difference between sex and gender that has allowed the idea of transition, both as a possibility and as a solution, to flourish.

Chapter 5

Chapter 5

Separation-individuation and fixed states of mind

The first case study in this chapter is Jane, a fifteen year old with a ‘hard, macho, external appearance’. Jane was convinced she was a man. She wanted a legal name change: she bound her breasts and wanted them removed. The therapist saw this as ‘a desperate wish to get rid of any evidence of her female self as well as her female body’.

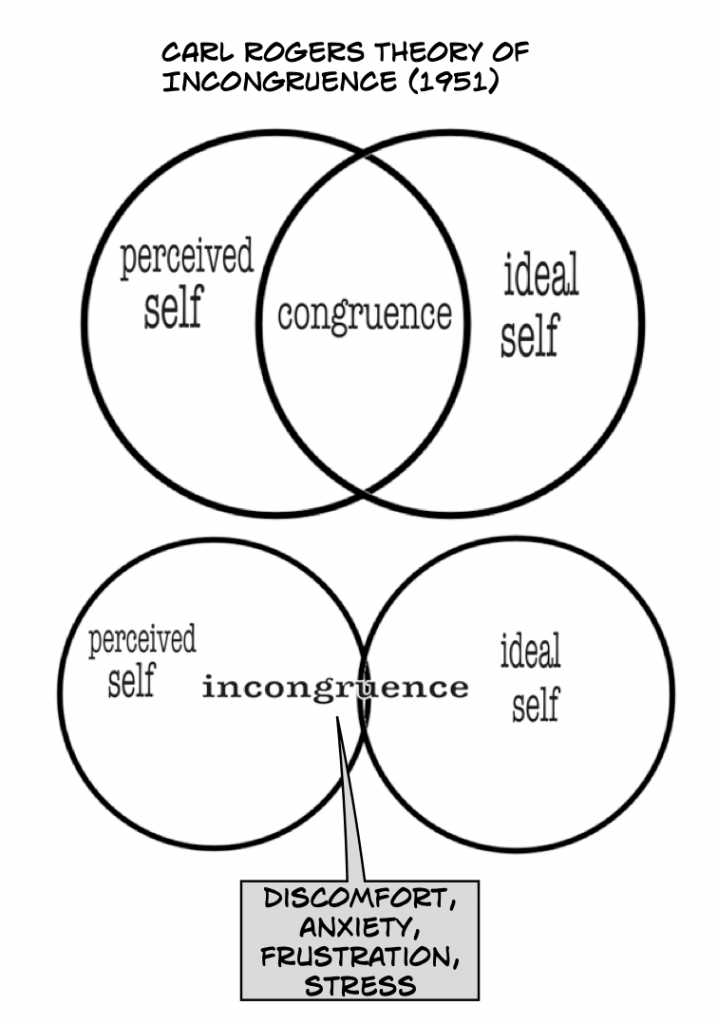

Feelings can be projected into the body while she (in this case, Jane) ‘ moves up into her intellect’. Of the obsession with gender, the authors observe “It is as if they believe all their problems would be solved if only they were the ‘right’ gender.”

The writers observe the Catch 22 that can arise: if the therapist tells Jane she should not remove her breasts it will look as if the therapist is trying to control her, if they do not, it may look as if the therapist doesn’t care. To comply with this view suggests the therapist may believe that psychic problems can be solved with medical intervention.

After two years of therapy, Jane began dating a girl from school and ‘felt she was probably lesbian not trans’. After this, therapy became easier and the therapist no longer felt they were ‘walking on eggshells’.

The second case study is that of thirteen year old Beatrice, a high-achieving, autistic child who dominated her family with moods and demands and developed a wish to transition after being rejected by a friend. Beatrice found her breasts and periods ‘disgusting’ and seemed to feel there was ‘no point’ in discussing things with the therapist.

A therapist, reiterate the Evanses, needs to carefully examine the anxieties that threaten to overwhelm a young person. Young people on the autistic spectrum may find it especially hard to deal with the changes brought about by sexual development and may feel they are poorly equipped to deal with adult life.

A therapist, reiterate the Evanses, needs to carefully examine the anxieties that threaten to overwhelm a young person. Young people on the autistic spectrum may find it especially hard to deal with the changes brought about by sexual development and may feel they are poorly equipped to deal with adult life.

Considering a variety of potential factors the Evanses note, among other ideas, that parents who have a history of being abused may project their own fears onto their daughters and even encourage transition as a means to protect their child. Additionally, a child who discovers as they grow up that they are not the ‘best’ may come to ‘believe their ideal state would be something or somebody else’. This can creates a phantasy in which the young person believes they can somehow leave any damage behind by transitioning.

Chapter 6

Chapter 6

Chapter six deals with adolescence: the authors remind the reader that “neuroscientists understand adolescence to be a process that is not usually completed until an individual reaches their mid-twenties, well into legal adulthood.”

With short, sub-headed sections on separation and rebellion; the importance of peer groups; fear of adulthood; adolescent development; disdain towards authority, and powerful defences, the authors observe that exploration of gender is a normal part of adolescent development which can ‘stir up all sorts of confusions, doubts and conflicts’ . They explore fantasies of adolescence, hatred of the sexed body and control of identity by enactment.

Detransitioner Dagny, who was deeply influenced by Tumblr, is quoted as saying “One of the unhealthy beliefs I had was that if you had gender dysphoria you must transition. And anyone that appeared to stand in my way was a transphobe- an alt-right bigot. If I myself questioned my actions, I was suffering from internalised transphobia.”

There is an indepth view of the case study of Eva, a non-identical twin who wanted to transition and had trouble dealing with her feelings of family neglect. Therapy gave her a place to explore her feelings and find other solutions.

The authors suggest that “the desire to transition often is related to a wish to control sexual development, and perhaps to defer it entirely, including in a literal sense, through the use of puberty blockers.”

The affirmative model of transition supports this idea. However, confusion and distress, they remind the reader, are a normal- and necessary- part of adolescence.

Chapter 7

Chapter 7

Excitement as a psychic defence against loss.

As children grow they become aware of anatomical differences between the sexes and that reproduction involves penetrating or being penetrated. This may bring up phantasies about damage and pregnancy and the child may develop a desire to avoid adulthood.

Children need parental help and support as they go through these stages and problems may arise when the child cannot let go of ‘the primary and often idealised dyadic relationship.’

They discuss the case of sixteen year old Chris, who self-diagnosed as transgender due to his feelings of being ‘more real and alive’ when dressed in girls clothes. At a family consultation the therapist felt Chris’s mother was anxious and his father was distant.

“Chris’s wish to get into his mother’s identity is perhaps based on an early insecure relationship with the mother…. in many ways his ‘transexual ideal’ seems to represent a way of taking on his mother’s identity so that he triumphs over feelings of dependency on and need of her.”

Whilst Chris appeared to have an improved state of mind when ‘in his female persona’ he also appeared to have doubts and anxieties, including fears that he couldn’t measure up to his father. The therapist in such a situation is confronted with the problem of trying to avoid re-enacting either of the parental relationship during therapy, and the authors discuss the problems that can arise in such circumstances.

Part Three- Gender Dysphoria and Comorbidity

Chapter 8

Chapter 8

The link between suicide ideation and gender dysphoria

The authors emphasise the importance of not separating gender dysphoria from other issues such as ADSD, ADHD, OCD, eating disorders, depression and anxiety. Patients may fixate on gender dysphoria and the idea of transition as a solution to all their problems.

David was a twenty-three-year-old man with a history of depression, anxiety and suicide ideation, whose mother contacted a therapist on his behalf. David’s suicidal feelings had appeared to vanish once he decided he wanted to transition. David had a troubled childhood with an absent and judgemental father and a high achieving brother, and had taken an overdose after his second failed attempt to get in to medical school.

The therapist focused closely on David’s relationship with his family members, especially his mother, seeing his wish to transition as connected to a wish to punish his parents for their failings, and his desire to become a doctor as linked to his desire to protect his mother from his father’s abandonment. At one point David snaps at the therapist:

The therapist focused closely on David’s relationship with his family members, especially his mother, seeing his wish to transition as connected to a wish to punish his parents for their failings, and his desire to become a doctor as linked to his desire to protect his mother from his father’s abandonment. At one point David snaps at the therapist:

“Oh, here we go, typical shrink! “It’s all your mother’s fault!”

Another suggestion the authors make is that:

“… the person can (attempt to) kill off an unwanted aspect of the self. This is also connected to a wish to kill the child who their parents gave birth to, perhaps unconsciously to punish them for their shortcomings as parents.”

This chapter also refers to the idea expressed by Campbell (1995) that “the individual believes that the attack on their own body will not result in their death as an observing part of the self will survive,” and Stekel (a mate of Freud)’s proposition that “anyone who kills themself has wanted to kill another or wished the death of another.”

So lots of stuff to think about there.

Chapter 9

Chapter 9

Patients with emotionally unstable personality disorder and gender dysphoria in mental health settings

This chapter deals with three case studies involving people who believed they could resolve issues of self-hatred and internal conflict by transitioning. It starts with the case of Michelle, who is described as a ‘trans-identified woman’. Shortly afterwards we discover that Michelle is, in fact, a trans-identified man.

The authors say they will describe this person as Carl (he/him) pre-transition and Michelle (she/her) post-transition. As is the case in real life as well as in books this results in confusion, for example a sentence that reads “however Michelle (at this point still called Carl and living as a boy) rowed with his mother…”

Michelle had a traumatic childhood, had been sexually exploited and was a prostituted drug addict both pre and post transition. Jessica, another male transexual (also described as a ‘trans-identifed woman’) had been raised in care and had a history of self-harm. Candice (likewise) had multiple diagnoses, including schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder.

“People with personality disorder do not like being reminded of their underlying fragility and dependence upon others- yet also hate for it to be forgotten,” observe the authors.

They emphasise the complexities of dealing with such patients and the need for a ‘triangular space’: psychoanalytic supervision for both individual therapists and teams.

Such patients are often prone to black and white thinking and believe that if they could change themselves completely everything would be alright. They may hope dramatic solutions can solve their issues.

“All the above makes them very prone to the rigid ideas and stereotypes of gender identity which tend to be promoted by pro-trans educational materials and websites.”

Chapter 10

Chapter 10

Comorbid mental health conditions and gender dysphoria

Paul was a medicated young man in his mid twenties who had little interest in life beyond watching TV in his bedsit. Paul had been admitted to hospital after threatening to shoot his mother with a replica rifle while in a paranoid state. He was on medication that was effective when he took it, but dependent on his mother to look after him. He was also impotent.

At the first session with the therapist, with no prior indication, Paul asked for a referral for a sex change. He said he had dressed in his mother’s clothes for years and since he had decided to transition the voices that plagued him had stopped.

“Paul tries to avoid feelings of humiliation around his dependence on the mother’s care by getting inside her identity and getting rid of his own… the patient wants to be inside the object, while on the other hand they quickly feel trapped within the object.”

Paul told the therapist:

“I will be left with nothing if I give up my wish to be a woman.”

Paul’s case is considered in detail. The authors observe that, for patients, the difficult work of coming to terms with the different elements of their personalities “challenges the individual’s often rigidly held conviction that they need to change gender… any comorbid problems need to be addressed and the link between this form of thinking and their interest in transitioning should be carefully examined.”

Part 4 – psychoanalytic theory, assessment, and technical challenges in therapeutic engagement

Chapter 11

Chapter 11

Psychoanalytic understanding of gender dysphoria

Ok, so hopefully I’ve got this right… here’s my very simplistic (and possibly slightly inaccurate) understanding of this position:

When a baby feels safe, it sees it’s mother as good. When it doesn’t, it sees her as bad. Balancing this good/bad object dynamic is difficult and sometimes the infant  projects the bad feelings out toward the world. (These bad feelings are the wicked stepmother of fairytales.) This is the paranoid schitzoid position. Eventually the infant settles for the ‘good enough’ mother. Once it’s resigned to this idea, it’s in the ‘depressive position’. In this position guilt about the bad feelings can overwhelm the little one’s ego and it can slip back to the paranoid-schitzoid position. Sometimes the baby can’t stop hating its parents for not being better but it hides these bad feelings from them and turns that anger in on itself.

projects the bad feelings out toward the world. (These bad feelings are the wicked stepmother of fairytales.) This is the paranoid schitzoid position. Eventually the infant settles for the ‘good enough’ mother. Once it’s resigned to this idea, it’s in the ‘depressive position’. In this position guilt about the bad feelings can overwhelm the little one’s ego and it can slip back to the paranoid-schitzoid position. Sometimes the baby can’t stop hating its parents for not being better but it hides these bad feelings from them and turns that anger in on itself.

The Evanses believe“many young people develop gender dysphoria in response to an earlier developmental crisis on the cusp of the depressive position…. a young person that bears a grievance towards his parents might attack his own body, his identity and his sexuality rather than attack the actual parents.”

The parents, who may be unwilling or unable to acknowledge these grievances, may respond by being complicit in hiding them by going along with the trans identity. Others may see the trans identity as erasing the child they love. Problems between parents and kids can cause a developmental fault line.

Later, in the section sub-headed container and contained you’ll be happy to know we are assured that the relationship between the mother and child doesn’t have to be perfect – it just has to be ‘good enough’. Oh, and the mum also has to believe she’s good enough whilst avoiding striving for perfection.

So phew.

We all have difficulties coming to terms with the difference between the sexes and the difference between the generations. Puberty raises all sorts of developmental issues concerning sex and the sexual act and many young people feel ill-equipped to face it. Some try to act super-grown-up, others act like little ones. Transition can seem like a simple solution to psychic pain.

Fifteen year old Sam didn’t make eye contact with his therapist, only saying that he was certain that he knew what he wanted and needed, and asking for hormones.

“The reality is,” point out the authors later in the chapter, “that doubts and anxieties about transitioning would be completely appropriate…

The rigid conviction that transition must be supported at all costs leaves no room for thoughtful examination.”

Sam didn’t want to explore the reasons why he wanted to transition. He just wanted hormones. The therapist felt guilty for encouraging him to explore the reasons why, because it caused Sam pain to do so. This is called projective identification:

“The ordinary doubts and concerns one would have about such a momentous decision are seen as threatening a defensive state of mind rather than as helpful thoughts designed to examine beliefs.”

The chapter goes on to discuss ‘mourning the loss of the ideal self’, the Oedipal triangle and the role of the father/partner.

When trans-identified children are encouraged by those outside the family to see their parents as bigots, the link between the generations is attacked. Some parents will go along with transition to avoid their own anxieties about their child growing up or to avoid confronting their own feelings of blame or fault. Children who are placated at every turn can begin to believe they should always get what they want. Concrete thinking can result in the patient viewing everything through the view of ‘trans’ and believing that all their problems will be solved if they can transition.

Ah, the minefield that is parenting. Other interesting ideas shared in this chapter include:

“Many people have heard of ‘penis envy’ but the truth is there are biological realities and differences between the sexes which seem to provoke intense feelings of exclusion…

the young person may avoid the reality of their limitations by denying the difference between the sexes…

(non-binary is) a fantasy the individual can triumph over not just rigid social stereotypes but also biological realities.”

The Psychic retreat

A psychic retreat is exactly as it sounds: a resting place, away from anxieties, in the patient’s mind.

A psychic retreat is exactly as it sounds: a resting place, away from anxieties, in the patient’s mind.

It can provide a defense structure but can also start to make life outside it seem unimaginable.

The Evanses cite the evidence that 61%-98% of children resolve gender dysphoria.

“We believe that gender dysphoria is a psychic retreat which most young people, if left to their own devices, will grow out of, or with support come to terms with… however those individuals who have become entrenched in a psychic retreat will likely need long term psychotheraputic treatment.”

The authors quote Sasha Ayad who wrote, “I find that when I take clients too literally, it can move us away from deeper exploration. I will try not to get wrapped up in jargon, recycled narratives and minute details in the client’s gender story… I listen for something deeper.”

The chapter goes on to talk about the psychotic and non-psychotic parts of the mind, transference and counter transference, normal and pathological projection, and the value of a psychoanalytic model for psychodynamic work.

It reflects on how the lack of a psychological model for thinking about gender dysphoria creates difficulties for clinicians working with this cohort, and how therapeutic work can be of benefit even to a patient who does go on to transition. Finally it notes that many who do medically transition continue to have mental health problems and symptoms of gender dysphoria.

Chapter 12

Chapter 12

Assessment and challenges of therapeutic engagement

‘Gender dysphoria’ is now called ‘gender incongruence’ in the International Classification of Diagnoses 11.

‘Gender dysphoria’ is now called ‘gender incongruence’ in the International Classification of Diagnoses 11.

“The patient might act almost as if they are a customer who has been sold the wrong suit and is outraged at the reluctance of the shop to give them a new one.”

The authors talk about how surgery and medication ‘cannot completely eradicate the patient’s natal gender’.

Again, I am bemused- of course it isn’t possible to eradicate a ‘natal gender’ because there’s no such thing as a natal gender. Either we are talking about sex or we are talking about stereotypes, and ultimately it is vitally important that we all know exactly what we are talking about! This conflation of sex and gender leads the authors to refer to, in the next paragraph, the upset felt by those who are subject to ‘mispronouning’. This term is used again later, in the case of Simon/Simone, a patient who flew into a fury at a receptionist when he was ‘misgendered’. While the term ‘misgendered’ is commonly recognised, the right term, I suppose would be ‘correctly sexed’.

This confusing use of language (Simone- a man- is also referred to as a ‘trans-identified woman) probably stems from a wish on the authors’ part to be gracious and considerate to those who have their own strong feelings about the use of preferred pronouns. However, when we are talking about sex and gender it is partly a willingness to inaccurately confuse the two that has got us into this mess in the first place.

This chapter also introduces John, a manic seven year old who (mostly) said he was a girl, would not separate from his mother and enjoyed dressing  in her clothes and make up. His mother was complicit in his claim to be a girl.

in her clothes and make up. His mother was complicit in his claim to be a girl.

The therapist speculated that John might be avoiding separation anxiety by ‘getting inside’ the mother. The writers explore the idea that both clinicians and parents may go along with a child’s gender dysphoria out of a desire to avoid causing them pain, but that sometimes the reasons behind pain need to be explored.

We are then introduced to James, 25, a detransitioner who had also been a manic child, putting off any potential suitors for his single-parent mother who had encouraged his lack of independence. John had realised he was autogynephilic when he noticed he became  aroused when wearing women’s clothing or entering their spaces. This could also be seen as an attempt to ‘get inside’ the mother.

aroused when wearing women’s clothing or entering their spaces. This could also be seen as an attempt to ‘get inside’ the mother.

“This is perhaps a different manner of entering a woman, which his father with an erect, potent penis, would have done to impregnate his mother.”

Often parts of the self that humans feel they have discarded may emerge when the ego is under pressure.

“We do not believe that it is helpful for the person to eradicate their natal self or unwanted aspects of their personality… we believe it is a mistake to go along with the idea that you can eradicate a hated part of the self.”

Concrete solutions to psychic problems

“If the individual has no concern at all about the prospect and outcome of medical intervention, this lack of concern should be thought of as a symptom that should be investigated.”

A young woman called Samantha is discussed: the therapist concludes that she associates sensitivity with being female and wishes to portray a ‘hard, masculine’ figure as a way to escape what she saw as the weak little girl inside her.

A young woman called Samantha is discussed: the therapist concludes that she associates sensitivity with being female and wishes to portray a ‘hard, masculine’ figure as a way to escape what she saw as the weak little girl inside her.

In an age-appropriate manner, the authors believe it is essential to ‘explore the person’s fears and phantasies about sex and sexual orientation’ and that doing so may eliminate the need or desire for the blockers which prevent the development of sexual characteristics.

It is also important to explore the grievances that young people may hold against their parents.

Questioning the validity of persistence and consistence as indicators of the presence of gender dysphoria, the authors observe that many young people presenting at gender clinics “appear to be frozen in the current occupations” and that these fixed states of mind should not be viewed as a reason for medical transition. Anxiety and doubt about such decisions would be “a very appropriate emotional response”. The authors do not believe it is possible to assess a child’s capacity to consent to such medical treatments.

“The fact is that human beings are complicated and our problems are usually multi-dimensional.”

The child’s rejection of their given name can also be a rejection of the parents and/or an attempt to kill off the part of themself they do not like. This rejection should be explored because “psychological maturity and mental health are based on an ability to tolerate different aspects of the personality”.

The child’s rejection of their given name can also be a rejection of the parents and/or an attempt to kill off the part of themself they do not like. This rejection should be explored because “psychological maturity and mental health are based on an ability to tolerate different aspects of the personality”.

It is important, they add, not for the first time, that therapists are given support and supervision when exploring the feelings of gender dysphoric young people.

Conclusion

“A thorough general assessment should aim to establish a picture of the young person’s personality, family dynamics, cognitive deficits, and possible psychiatric disorders… this includes an understanding of the family and social context in which the gender incongruence has emerged.”

Many people use daydreams to help us through life: a trans identifying child can easily become fixated on the idea that transition will solve all their problems. Often a trauma or developmental hurdle ‘threatens to cause a psychological catastrophe’ and the child views transition as a solution.

The theory that changing the body can resolve psychological problems needs to come under much greater scrutiny, suggest the authors. Plastic surgeons often refer patients to psychiatrists when they sense that this is a solution which is being sought by a patient. Medical and surgical interventions do not deal with the underlying problems which caused the gender dysphoria in the first place; these issues remain unresolved.

Gender dysphoric patients often put a great deal of pressure on friends, family and doctors to go along with the idea that transition is a cure-all. But the body is a part of the whole self and this view does not consider the fact that young people’s identities frequently change as they mature.

“Patients with gender dysphoria need services that are protected from political activism; the professional involved need to be able to work in an environment that is protected from political intrusion. A rigid ‘one size fits all’ approach is unhelpful and potentially harmful.”

You can purchase a copy of ‘‘ from Phoenix publishing house here and from Amazon here.

You can purchase a copy of ‘‘ from Phoenix publishing house here and from Amazon here.

You can read the authors’ blog on psychotherapy and gender identity here.

You can follow Susan Evans on Twitter @sueevansprotect and Marcus Evans @marcusevanspsyc and visit their website here.

This review may read a little like a synopsis in places: the ideas expressed are so specific and thought provoking that I found it hard to work out which aspects of the book to address and which to ignore. Hence a rather lengthy review which should in no way be seen as a substitute for reading the book itself, which I highly recommend you do, whatever your interest in the subject.

The thing that struck me most strongly on finishing the book is how blind sided we have become to the fact that gender dysphoria is a disorder. Gender ideology has many people believing that it is possible to have a male brain in a female body: it overlooks the fact that when a physically healthy human being believes themself to be something which they are not, their problem lies within the mind.

Get hold of a copy, get reading, Susan and Marcus Evans have produced an important and thoughtful book here, a must-read for anyone with an interest in this field.

Firstly, thank you for taking the obviously great effort to produce such an expansive summary. This is a medical abuse scandal that will surpass thalidomide, lobotomies and eugenics – the Evanses are very brave to take this issue on given how aggressive the trans activism has become.

There is a too-short mention of the medical professsionals in this field being influenced by psychological factors ie omnipotence… A teasing opening to a subject should be fully investigated. Having paid close attention to this subject for some time it is quickly apparent that the field of “gender medicine” is full of practitioners who have a close personal motivation toward the subject matter. Tracing the names of many practitioners in the field reveals quickly many are transgender. Are these doctors doing what is best for their patients of “recruiting” them to affirm the doctor’s own status or ideological position?

It may not be the most polite question to ask, but given the damage done I think we’re beyond asking politely.

The most strikingly perverse irony of (so-called) “gender dysphoria” is that: for what it purports to represent, at its core, really CAN’T EXIST *without* every single backwards social stereotype (or I’d also venture: a lot of child abuse being covered up in the situations of these families indoctrinated by it) constantly being reinforced INSTEAD OF BEING REBELLED AGAINST.

All its obsession with “male/female role playing” seems stuck in some-sort-of a boorish cult of religious and economic pornified consumerism.

Thank you.