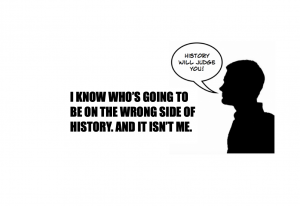

Owen Jones wrote in the Guardian today that those who don’t support transgender rights (although he is unclear exactly what he means by that) will be on the wrong side of history.

‘Anti-trans zealots,’ he proclaimed dramatically, ‘know this: history will judge you.’

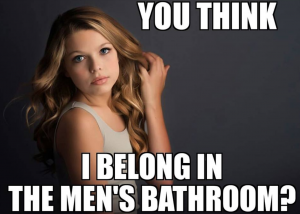

Jones’ article – like so many before it, and undoubtedly like so many yet to come- was illustrated by a photo of a blonde, long-haired boy-child sporting a large pink bow, accompanied by an excited and glamorous mother. The boy is probably not more than ten years old. He is clasping a sign that reads ‘Please let me use the girls’ room’. This is a shameless exploitation of a child and puts me in mind of another trans-identified little boy, Corey Maison, who has also been used in the ‘battle’ for trans rights . Of course nobody is bothered by little boys using the women’s bathroom. I have a friend who frequently takes her long-haired, small-for-his-age, 12 year old son into the Ladies with her and no-one blinks an eye. Women know that the men’s room is unlikely to be a safe place for pretty little boys.

Corey Maison, posterchild for the bathroom movement.

.

These articles are never accompanied by a photo of a 6ft tall bloke in a wig & a dress, with 5 o’clock stubble, captioned ‘You think I belong in the men’s bathroom?‘ for good reason. Because we bloody well do, yes.

Owen Jones, of course, has the upper hand here. He is a journalist for the Guardian & I am a not-very-prolific blogger who spends way too much time on Twitter. Jones has never deigned to answer me when I’ve tagged him on Twitter: why would he? After all I am a bigot, full of hatred, scared and scornful of trans people, a mad, bitter hag who wishes to erase them all and leave brave transgender children to spend a lifetime trapped in the wrong body…

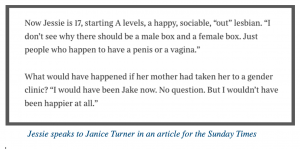

… except I’m not. I’m the mum of a teenage girl who identified as a boy for nearly a year – insistently and persistently- the mum of a girl who is now a happy lesbian. I did not support my daughter Jessie’s transition and, as she told Janice Turner in a recent interview for the Times, Jessie believes she would probably have been on testosterone by now if I had done so. A friend of Jessie’s, Hazel, identified as a boy for over a year. Hazel is now a glamorous young woman who dresses in conventionally female clothing and dates boys. So I know, first hand, that children DO desist, baby-butches and glamourpusses alike. This is not rare.

In general, kids that desist are a bit embarrassed by the whole thing. They don’t want to be paraded through the press, admitting they ‘made a mistake’, or to be on the receiving end of accusations of transphobia and deception: they just want to forget about it and get on with life. You won’t hear much from them. You won’t see photos of them in glossy magazines & on the internet. Their parents are mostly so thankful that the whole awful scenario is over that they also want to move on and who can blame them? Some of us, however, are so horrified at the level of beguilement and damage going on that we won’t shut up; that we can’t shut up. But I digress.

When Owen Jones wrote in the Guardian today that those who don’t support transgender people will be on the wrong side of history, he was a little late to the party: that cry has been fashionable for a while now. I first came across it when it was thrown at me by a young woman boycotting the gender debate at the Women’s University Club. “You’ll be on the wrong side of history! You’ll see!” she screamed, as I entered the building. It seemed a strange accusation at the time and it stuck in my head. Surely we believe what we believe: you don’t change your mind out of fear that the majority might not agree with you at some point in the future. Since then the cry has gained popularity. I’ve heard it over and again on Twitter. It’s almost as popular as the mantra ‘transwomen are women’. Transwomen are NOT women. How do we know this? Simple. Can I be a transwoman? No. Why not? Because I am not a man.

How can a man know how a woman feels? He can’t. The one thing that unifies woman- infertile women, post-menopausal women, menstruating women, breast-feeding women, lesbian women, het women, young women, old women, feminine women, GNC women – even women who think they are men -is our biological experience of being female-bodied. THAT is what a woman is and that is what the word woman describes. Females bleed. They give birth. They feed their young. Not every woman experiences these things but when it comes down to it, we all know what a woman is. We all came out of one.

People like Jones can play around with words, they can try to redefine them; they can tell women they are bigots for not accepting men as women and many women will go along with it ‘because it seems unkind not to’. Most of us are well-trained like that. We want to be good trans-allies.

Jones speaks of ‘brilliant trans voices emerging – like Shon Faye (and) Paris Lees’

Er, hang on, you mean Shon Faye who told people he referred to as ‘children’ to ‘suck dick, get tits early’? The same Paris Lees who wrote a ‘bathroom’ article accompanied by a picture of himself sitting on the toilet? Paris Lees who routinely calls lesbians who don’t want sex with men ‘transphobic’? Inspirational stuff indeed.

Shon Faye tells ‘children’ to ‘suck dick’ and ‘get tits early’.

Jones tell us that trans people aren’t hurting anyone. Well, it’s true that you don’t often hear trans-identified women demanding to use men’s bathrooms, although I’m sure some of them do, and the chant ‘transmen are men’ is bandied about far less than its blushing feminine equivalent. In fact, you don’t hear much from trans-identified women, full stop. Despite claims that trans-identified women have male privilege, they are remarkably quiet about it all. None of the three ‘brilliant trans-voices’ that Jones refers to in his article belongs to an actual woman. Yet trans-identified men calling themselves women are demanding access not just to women’s toilet facilities, but to women’s refuges, clubs, sports teams and colleges. They are being housed in women’s prisons. They are joining lesbian groups, becoming Women’s Officers, and closing down women’s events for excluding them. They are trying to redefine womanhood as a feeling, which by implication suggests that women who don’t identify as men are quite happy with the discrimination we face – after all, if we minded that much surely we’d all just identify out of it?

Jones likens gender critical women to those who opposed LGB rights in the 80s. How dare he? While #LittleOJ was still being fed on mummy’s milk, I was kissing girls- and boys- in the woods at school. While #LittleOJ was not long out of nappies, I was protesting against Clause 28.

The problem with Jones’ article, the reason that it never really gets going, is that it is based on a lie.

Transgenderism is absolutely nothing like LGB. The LGB fight for acceptance & equality is nothing like the fight for transgender rights. The two are worlds apart. They are not comparable.

Transgenderism is absolutely nothing like LGB. The LGB fight for acceptance & equality is nothing like the fight for transgender rights. The two are worlds apart. They are not comparable.

LGB people and their allies know that our bodies do not define who we love or desire. Men can love women and women can love men and that’s just fine. A female-bodied person who loves other female-bodied people is a lesbian. How can a man possibly be a lesbian? The claim is absurd. Attraction is a feeling, our physical bodies are not a feeling. LGB does not advocate that bodies should be modified to fit stereotypes. LGB doesn’t care what we wear or what hobbies we have. LGB wants to get rid of those stereotypes! LGB people do not demand that the rest of society complies with a delusion. LGB rights ask that we are all accepted just as we are, whatever body we are born in. The LGB fight for equal rights is not dependent on the erasure of the rights of another marginalised group and LGB people do not go into schools asking little kids if they might be gay.

So no, @OwenJones84 I will not be on the wrong side of history. History will not judge me and my concerned sisters and brothers who are being silenced by your accusations of hate and demands for no-platforming.

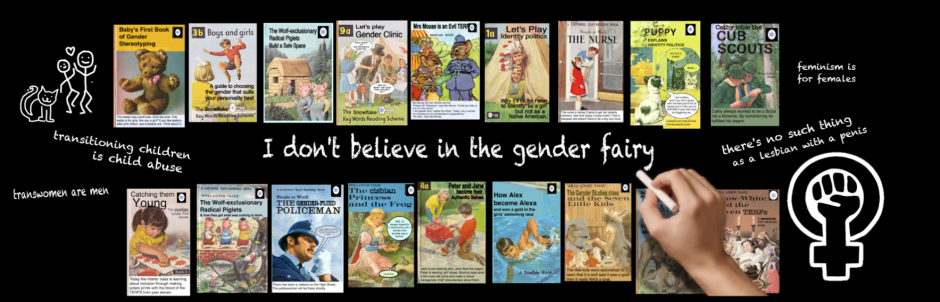

History will judge those who beguiled & medicated a generation of gender-non-conforming children; those who transitioned gay boys & lesbian girls; those who told a girl she could become a boy and vice versa, when they knew it wasn’t true. History will judge those who told kids there was a ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to be a boy or a girl and those who told a generation of baby-dykes they could become ‘straight’ boys. Boys who like dancing & pink & sparkly hearts & tutus are being told this might mean they are a girl. People are going into schools right now and telling kids these things. How is that progressive?

History will judge those who denied kids a puberty; with all its angst, stresses and pain, it is an essential part of forming us into the adults we become. History will judge those who have left now-adult men with non-functional 1” penises; those who cut the healthy breasts off girls who were still children. History will judge those who skinned the thighs of young women to make penises that will never work.

History will judge those who lied about & glorified suicide stats in the press; who told kids that ‘real’ transkids self-harmed & tried to kill themselves. Over, and over, and over again. History will judge those who say puberty blockers are harmless and reversible in all cases; that nothing permanent is done to children. That isn’t true. Girls as young as 14 have had their breasts removed & the CEO of Mermaids took her son abroad to have his penis removed when he was just 16. History will judge the parents who told their disturbed kids they could ‘get a penis when they’re bigger’ and that ‘people out there want to erase you’; the ones who spanked and screamed at their GNC kids for playing with the ‘wrong’ toys, and prayed to their judgemental gods for an answer. And history will cry with the parents who didn’t realise what was going on until it was too late; who trusted the doctors & therapists who told them this was the best thing for their child, who believed the press & lost their quirky, confused kids to the cult of transgenderism.

History will judge the therapists and surgeons who made blood money out of this. The gender therapists who befriended confused girls on social media and posted quirky jokes on Twitter to draw them in; who offered them hormones and pocketed the profit, calling it ‘care’. You know who you are. History will judge the surgeons who cut healthy body parts off children for money and to satisfy their own curiosity. You want to talk about Nazis? Nazis experimented on humans too. How do you sleep at night? There should be a special ring of hell in Dante’s inferno just for you.

History will judge those who fought for laws that said any man can walk into a women’s bathroom or changing room & that an uncomfortable woman has to STFU. History will judge those who shouted ‘TERF’ and ‘bigot’ at women who were only trying to protect their children & at feminists fighting to preserve their hard-earned rights.

Today’s pro-trans media is promoting sexual stereotypes; eradicating a generation of young gay & lesbian kids & condemning them to a lifetime of medicalisation.

History will judge YOU, little OJ, with your male privilege & your not-very-well-written & badly-researched articles. Inspiring stuff, indeed. You are complicit with the eradication of women’s rights & the medicalisation of a generation of kids. And you’re not stupid. In your heart, you know it.