Have you filled in the government consultation on the Gender Recognition Act? If you’re reading this after 19th October 2018, your chance to do so has passed. If you’re reading this before then, carpe diem. You still have a chance for your voice to be heard.

As Nicola Williams of Fair Play for Women says “We have one chance to stop this.” This is it.

In their distinctive red T shirts, women have been campaigning all over the country.

*The quotes from ‘Fair Play’ women (presented as conversations in a cafe for the purpose of this piece) and preceded with a red asterisk * are the words of actual individual campaigners, given to me for inclusion in this article.

I salute every one of them. Names have been changed.

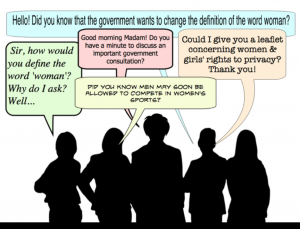

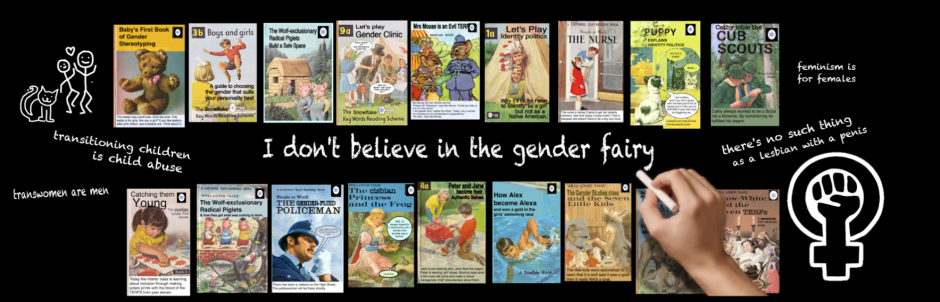

Over the last few weeks, the women of Fair Play for Women (FPFW) have taken to the streets of England where they’ve been talking to members of the public and trying to explain what changes to the GRA could mean for the rights of women and girls nationwide. In their distinctive red, white and black T shirts, emblazoned with the slogan ‘Hands off my Rights!’, women have been handing out leaflets and encouraging people to fill out the consultation in places as far afield as Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Cornwall. You can see details of their work at Fair Play for Women, and you can also get guidance to help filling in the consultation here. You can have a look at the resources in their excellent library here.

If you’re reading this you’re probably already familiar with the Gender Recognition Act (GRA), but it wouldn’t do any harm to give a bit of a background refresher. Firstly, it’s not to be confused with the Ghana Revenue Authority, which is the first thing that will come up if you type ‘History of the GRA’ into Google. The GRA was established in 2004 to enable trans-identified people to ‘receive legal recognition of their acquired gender’.

The government’s helpful leaflets on the proposed changes to the GRA are astoundingly biased. For those of us who have really educated ourselves about this matter and don’t support the changes, flipping through the ‘Easy Read Factsheet’ is quite a depressing experience. The assurance that there will be no changes made to the Equality Act, for example, is misleading. When a man can simply change his birth certificate to say he’s a woman, then there’s no way of telling who actually IS a woman. Making this process a matter of simply signing a form renders The Equality Act completely meaningless so far as protecting single-sex spaces is concerned.

The government ‘fact’ sheet

The first page of the startlingly sexist ‘Easy Read Fact Sheet’ features a picture of a pearl-clutching, be-lipsticked man, smiling widely at the camera, while a much smaller picture shows a young woman happily educating herself from a large pink booklet. It’s so easy, a woman can understand it!

Page 2 tells the reader, ‘Trans is the word for someone who has changed their gender from the one that was given them when they were born.’

My head is in a spin already. Nobody is ‘given a gender’ when they are born. Our SEX is observed and recorded. So already, in the first sentence, the ideas of sex and gender are being confused. We are already battling the word salad. Come on government, you can do better than this, surely?

The leaflet also tells the reader, “If you are married you need the permission of your spouse”. Well, it’s true that if you want to stay married (and your wife is quite happy to suddenly become a lesbian) then yes, she needs to agree to the legal change. The current position offers a dignified way out of a marriage which has quite possibly become untenable for the other partner. But heck, this isn’t about actual women, is it? On the government leaflet this point is accompanied by a picture of a blue-haired man in a choker and a low cut top, with a smiling woman giving a thumbs-up next to him. (He is not smiling. Only actual women are expected to smile all the bloody time.) It’s easy! Smile. I mean, what reasonable woman would object to her husband suddenly ‘becoming’ a woman?

Transmen, quelle surprise, are not given much thought in this document, although it does feature a couple of pictures of a fairly sullen teenage girl with short hair. I suspect she isn’t meant to be an actual female because she isn’t smiling. In one picture she wears a crop top and a tie! Gasp! Non-binary or gender fluid? You decide.

‘There will be no change to women-only spaces and services’ the helpful factsheet reassures the reader. Which brings us back to the fact that if there’s no way of telling who was born a man or a woman, women-only spaces become a bit irrelevant, don’t they?

The government says it wants to make the process of ‘changing gender’ easier, and that the consultation is only about this.

The government says it wants to make the process of ‘changing gender’ easier, and that the consultation is only about this.

The only thing left that currently takes any time, money or effort to change is your birth certificate. Other documents are already a done deal. If you want to make things even easier, there’s only one way forward.

Yes, that’s right. You can already change your sex on all your legal documents. You might be surprised to know that anyone can already change their sex on their driving licence and passport without undergoing any sort of process other than filling in a form. Sounds unlikely? I didn’t believe it either. It’s true. There’s a woman in one online feminist group who still has a ‘male’ driving licence after seeing if she could change it. There was no problem. To change your sex on your passport just requires a signature from a ‘reputable’ person. Note that these changes are made to your recorded SEX and are done quickly and easily.

So why the need to make things easier? The thing that surprised me most about the GRA is that a man can already change his sex on his birth certificate. You might be forgiven for thinking the consultation was to see how the public felt about that. Many of us think that the government should be saying, ‘Woah. Changing your sex on your birth certificate? No way, bro.”

So why the need to make things easier? The thing that surprised me most about the GRA is that a man can already change his sex on his birth certificate. You might be forgiven for thinking the consultation was to see how the public felt about that. Many of us think that the government should be saying, ‘Woah. Changing your sex on your birth certificate? No way, bro.”

Instead, what the government is thinking of doing -what they are telling us they plan on doing – is making it as easy to change your sex on your birth certificate as your passport. Currently, if you want to change your actual birth certificate, you have to ‘live as a woman’ for 2 years, get a medical diagnosis of ‘gender dysphoria’ & get a doctor to give details of any medical treatment; sign a piece of paper saying you’re not going to change your mind, and pay £140.

This is the only thing standing between us and sex self-ID.

Take away this barrier and absolutely any man can legally become a woman in a few sweeps of the pen or taps on a keyboard. This change would be totally unreasonable.

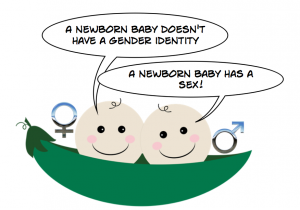

Many of us are wondering how legal this process is. A man is born a man and a woman is born a woman. This is, at least for now, enshrined in law. For a legal document to be changed saying a man was born a woman is surely an illegal process. He wasn’t. A new born baby does not have a gender identity – hell, I don’t have a gender identity, but let’s not digress – a new born baby has a SEX. Saying a man was born a woman is a downright lie. Yet this can already be done by following the process above, and this has been the case since 2004.

Some people will say,“But trans people have been able to do this since 2004, and there haven’t been any issues, so what’s the problem?” Well, firstly, make no mistake, there have been issues. The latest high profile case is that of Stephen/Karen White, a trans-identified man who was put in a women’s prison- despite a history of rape and child sexual assault– and who was charged with sexually assaulting no less than four women within a few days of arrival. This case involved perhaps the most absurd words ever spoken by a prosecutor when Charlotte Dangerfield told the court, presumably with a straight face, “Her penis was erect and sticking out of the top of her trousers.”

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly – this isn’t really even about people who call themselves transgender. It’s much bigger than that. What the government wants to bring in is ‘sex self-ID’. And what it means is that ANY man – yes, any man, your great uncle Bert, that bloke who works in the betting shop, that creepy guy that hangs around outside the school at the end of your street – they can all just say they’re a woman, and bingo! It’s a done deal. Fill in a form and get that M changed to an F. Access to women’s spaces R Us.

Fairplay for Women has made several short videos about on the subject of sex self-ID and you can watch them here. While Dick Travers approaches the issue from a comedy angle, the first, much darker, video of the series is shot from the point of view of a woman who has suffered a lifetime of abuse at the hands of men and is now rebuilding herself.

” I owe my life to female only groups,” says her voice. ” To crisis centres and refuges where I could be safe, to other women who gave me strength to face my past: showed me I wasn’t alone; let me be angry; let me breathe. And let me say the truth. That the rapist was male. The body was male. The weapon was male. The violence was male. And his belief that it was his right was male too.”

I was ready to go out campaigning.

There are several FPFW campaign groups in London and the surrounding area, so with the end of the consultation only a few weeks away I bought myself a T shirt (you can get yours here), signed up and went out leafleting with some local women.

I met them in a COSTA coffee shop, a group of seven cheerful, positive women aged between about twenty five and sixty. I couldn’t have missed them: already wearing their ‘Hands off my Rights’ T shirts they looked a little like a patch of poppies planted in the earthy brown colours favoured by the decor of COSTA.

“COSTA coffee is TERF central these days,” joked Kath, as we shared a muffin and shared out the campaign leaflets and postcards. I asked them about their experiences leafleting. I was a little nervous myself, but Kath reassured me.

I asked them about their experiences leafleting. I was a little nervous myself, but Kath reassured me.

* “I’ve been absolutely terrified and totally out of my comfort zone every time,” she confided, “but every time I’ve been happily surprised by the reception I’ve got from ordinary people who get it, who say ‘but what about hospital wards?’ or ‘what, no operations necessary?’ and who want to take postcards and leaflets to pass on to their friends and family. Every time I’ve met another brave woman, I’ve felt like we are part of something really important, and that we are absolutely doing the right thing. And every time I leaflet, I have to totally talk myself into it! But I am so happy I have contributed in my small way. It has made me braver in real life too, and for that I am glad. The leaflets are clear and simple to understand, the films really hit home, and the other brave women I have met are inspiring.”

* “I’ve found it incredibly heartening.” said Laura. “Nearly everyone agrees with us. It’s easy to forget that outside the twitter bubble, very few people actually agree that “transwomen are women” and even if they do, they think that transwomen are men who have actually been through the operation and are astonished to learn that most of them are just transvestites. Even those who say “yeah, people should be what they want”- when you probe a bit further and ask questions, they realise they haven’t thought it through and that yes, we do need protections for women to be properly considered.”

* “I spoke to a woman in Dartford who is a rape survivor,as am I.” added Maria. “She was really emotional and said she was hugely grateful to us all for raising awareness as the prospect of self ID terrifies her.”

We finished our coffee and walked out onto the High Street. There was an open square near the cinema, a mostly-pedestrian crossroads, and this was where we were going to begin leafleting. I could just hear a busker playing ‘Brown-eyed Girl’ and make out some small children dancing at the top of the street. A woman grasping a huge bunch of giant balloons stood outside the newsagent, and Elsa and a Transformer tumbled and twisted together in the breeze. The street was filled with shoppers, couples out with kids, teens and pensioners in small groups. They all looked fairly purposeful. I swallowed and approached a woman in her 30s, proffering a leaflet. She had long brown hair and glasses, I realised I’d automatically reached for a leaflet with a photo of Helen Watts on the front, because she looked a bit like her.

“Excuse me,” I started. “Could I give you a leaflet about women’s rights?”

For a moment it seemed she wasn’t going to stop, but at the words ‘women’s rights’ she looked more interested.

“Thank you,” she replied, taking the leaflet. I watched her walk up the street, moving more slowly now, as she read the leaflet. Then she popped it in her handbag, looked back at me and smiled.

I felt ridiculously heartened by this small victory and decided to be braver next time. Next time I would try to start a conversation!

“Hello,” I tried, chirpily. “Did you know the government is considering changing the definition of woman so any man can just declare himself to be female?”

It was a bit wordy, but the couple I was talking to stopped. The man chuckled.

“No really! You Sir, if the current changes go through, you could just sign a piece of paper and get your birth certificate changed to say you’re female.”

“Nah! Is this about transgender rights?”

“It’s not really about men who believe themselves to be women,” I told them. “It’s about any man being able to make that change legally, really easily. It’s called sex self-ID… “

A few minutes later the couple walked off, having taken a leaflet and a postcard. When the woman turned back and asked for a few extra leaflets to give women at her book group. I felt absurdly proud.

The next five or six people I approached either ignored me completely or looked at me with distaste, as if I might be trying to sell them something. I felt that some of them thought I might be a bit bonkers. I spoke to Maya about this feeling when we went for coffee afterwards. She agreed and said she’d had similar feelings herself.

*“Something I said to a lot of people” she told me, “was ‘anyone could be a woman.’ And a fair few people stopped at that, wondering what I was talking about. On the faces of those who didn’t stop, I often saw a little smirk and shake of the head which seemed to suggest they thought I was crazy; some mad woman in the street who doesn’t understand how the world works, spouting nonsense to people who have better things to do. And the thing is,” she sighed, “they’re right; it is nonsense. But nevertheless it is something that’s happening. So although it’s a disheartening experience having so many people walk past you uninterested, that’s really balanced out by those who do stop to talk.”

So there I was, standing in the middle of the street, trying not to feel disheartened, and to get my enthusiasm back, when a tall, grey-haired man in his 60s approached me, waving a leaflet.

“Your friend just gave me this,” he said, shaking his head. “It’s very interesting. But this can’t possibly be right? ALL the major political parties support this change?”

“They do,” I said. “It’s very difficult for people to speak out against it for fear of being called transphobic.”

“But women NEED single sex spaces!” he said indignantly. “Of course they do! My granddaughter…” He trailed off, looking worried.

“There’s still time to let the government know what you think,” I offered. “On the Fair Play for Women’ website there’s a booklet that can help talk you through filling in the consultation. It doesn’t take long.”

“Thank you, yes, I really think I will,” he assured me.

My confidence restored, I chatted with several other people including two older women, who were astonished and rather angry, and assured me they would fill the consultation that very afternoon.

“On our phones,” one of them offered. “Over lunch.”

“There is one more thing I’d like to ask you, darling,” her friend turned to me. “Do you know any decent Greek restaurants around here?”

I spoke to a woman who worked for the NHS, who said she’d take some leaflets to work. She promised she’d fill in the consultation herself at lunchtime, hoping a colleague would do it with her.

I spoke to a mum with three children who took a leaflet and a postcard and said she’d fill it in once the kids were in bed. “I’ll tell my sister about that website too,” she added.

Laura seemed to be being monopolised by a large bloke so I drifted over to see what was going on.

“I don’t believe in this women’s rights stuff,” he was saying. “Women’s rights? Pah! Women should just stand up for themselves!”

“That’s what we’re doing.” pointed out Laura, reasonably.

“My Missus wouldn’t take no crap in the toilets, not off anyone, male or female. Men in women’s sports teams? Just kick ’em out. Bet you can stand up for yourself,” he added. “Big girl like you! You’ve very tall, aren’t you?”

Laura sighed. “We have to go now,” she said firmly, and we moved nearby to where Kath was talking to a young couple. Once she’d finished her conversation we decided it was time for a well-earned break, rounded up the others and headed back to COSTA.

* “As a middle of the road, middle-aged mum I don’t class myself as radical,” Sara said, sipping a cup of green tea. “The lack of public awareness of the proposed changes to the GRA and bullying and silencing of women only dawned on me a few months ago. When the penny dropped I was furious and determined to be brave and speak out! As a domestic abuse survivor, I’ve learnt the hard way what male control looks like and the need for boundaries to keep women safe. I’m confident now to assert boundaries for myself and my fellow women and girls. In joining the campaign, I’ve found a home to discuss women’s rights and make a difference. I’ve met great women from all different backgrounds but all eminently sensible and calm! The response when leafleting has been overwhelming positive, I see people of both sexes and all ages shocked and often cross when the penny also drops for them. The public don’t want these changes, the majority don’t care about gender identity, live and let, but they are cross at the government’s proposal to accept a lie and legally shift the definition of sex when we all know that biological sex can never be changed.”

* “Watching people realise what is happening makes it all real.” nodded Karla. “You never know how anyone is going to react. Some are appalled. They can’t believe it. They don’t know why gender self-identification was ever suggested. Some look at you and say “I know what this is about and don’t want to talk”. But most are astonished. One young man, out with his very pregnant partner asked: ‘Does that mean we can choose which sex we are going to have? ‘ He was dumbfounded.’

* “Ordinary people are shocked when they hear what the government are proposing,” agreed Trish. “Most haven’t heard about the consultation and are very grateful to be informed. Many people I’ve spoken to have read a story in a newspaper which had alarmed them – the rapist in the women’s prison, Girlguiding policy, the man allowed into TopShop’s women’s changing-room – and they were angry and disbelieving that the government would support such policies.”

Had nobody disagreed with her, I asked Trish, called her names or supported the changes?

* “No,” she shook her head. “Men and women, young and old, all were equally horrified at the idea that men might be able to simply self-identify as women to become women in the eyes of the law.”

*” Most people have been really interested and supportive, but I have met some who disagreed with what we’re doing,” interjected Sonia on my left. “Three of us were leafleting near a museum when two young women approached us. They said that they’d read the leaflet and wanted to let us know that what we were doing was transphobic, and that anyway women were just as likely to assault men as men were women- which of course we know isn’t true. We said it wasn’t about transphobia, it was about men being in women’s spaces, and we asked them how they would define ‘woman’. They said being a woman wasn’t about biology. “It’s more of a feeling,” said one, but she couldn’t be any clearer. It was surreal: they were both educators in their late twenties, both mums with toddlers. They said what we were doing was hateful and that they were going to tell somebody in the museum to get us stopped. One of the women in our group felt really nervous about that happening, so we left.

* “But last week,” Sonia continued, “we popped into a branch of Starbucks for a hard earned cuppa after leafleting. My friend asked for ‘adult human female’ on her cup of coffee, and the woman that served us said, “I’ve seen you lot on Twitter and I’m behind you 100% and I love those stickers that are going around, too. If I didn’t have this job and my son to look after I’d be out there leafleting with you.” And that was a great feeling. So you take the good with the bad.”

We finished off our drinks and cake crumbs, went back out onto the High Street and spent a further half an hour handing out leaflets and talking to people. Some were too busy to stop, others were happy to have a chat.

One woman told me, “Oooo, I’m past all that now, love. Leave it to the younger ones I say!”

Laden down with shopping bags, another said, “My hands are full but it looks interesting! Drop it in my bag and I’ll read it later.”

“I saw something about this on Facebook,” said another. “I’m a classroom assistant and we’ve been talking about this in the staff room at school. It’s just wrong. Give me a few different postcards and I’ll take them in on Monday with some biscuits.”

“What’s this about then?” called a man passing by with his two small daughters. “I care about women’s rights! Well, I’ve got to, eh?” he grinned proudly at the little girls next to him.

I explained how single-sex spaces were under threat by the idea of sex self-ID, how there was only a short amount of time left to fill in the consultation and how the fair Play for Women website could help him fill it in.

“I’ll do it when I get in,” he promised. “My wife will have something to say about this as well. Can I take a few of those leaflets? I know she’ll want some.”

“Can I have a postcard too, daddy?” asked the eldest. I handed her one and they skipped away happily.

The street was getting quieter and a slight chill was in the air. Another group of women had been leafleting a few miles away and had arranged to meet us for a chat before we all went home. Kath came over to say she’d received a text saying they’d arrived. Back we went to COSTA for the third time that day. The other group had grabbed a set of comfy sofas at the back of the cafe, where we joined them.

I asked them their experiences leafleting.

*“It was really difficult walking up to strangers to talk to them about this.” said one. “I’ve never done anything like this before. Although it’s a disheartening experience having so many people walk past you uninterested, that was balanced by those who did stop to talk, and I’ll definitely be going out leafleting again.”

* “For me, it was genuinely enjoyable to be actively doing something rather than feeling angry and helpless reading about all this at home.” put in a young woman called Sandra. “It felt good to be informing the- grateful- public about the consultation. It could change their lives and yet many knew nothing about it. I spoke to a teenage girl today who was really interested. She understood the issues straight away and wanted to share the info with her school. And I spoke to a man and woman with two kids who stopped to talk, thanked me for giving up time to protect the rights of their children, and took leaflets for their friends. Broadly, people were very pleasant.”

* Well, I’m angry at having to campaign with Fair Play for Women!” said another campaigner, stirring her tea crossly. “How can we be fighting for the right to exist in 2018?! Talking to shoppers was reassuring though, everyone agrees that it’s madness to deny that men are men and women women. But how many will find the time to fill in the consultation?” She shook her head. “Who is listening to them?”

If you can fill out a response to the consultation, please, please do. Time is running out.

To submit to the consultation with the help of the Fair Play for Women guidelines, click here.

If you really don’t have the time to submit a response you’ve composed yourself, Fair Play for Women have designed a simple prototype response which you can read. If you agree with the wording, you simply fill in your name, address and details and they’ll email it to the government for you. You can click here to fill in the simplified response.

Back to the tale in hand. I arrived at Westminster Magistrates and passed through the huge glass doors. The court was built in 2011 and the architect was clearly a fan of glass. Security was understandably tight. My bag passed through an Xray machine, I passed through a metal archway and headed up several flights of stairs to find Court Nine.

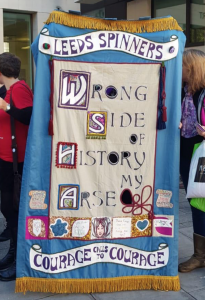

Back to the tale in hand. I arrived at Westminster Magistrates and passed through the huge glass doors. The court was built in 2011 and the architect was clearly a fan of glass. Security was understandably tight. My bag passed through an Xray machine, I passed through a metal archway and headed up several flights of stairs to find Court Nine. I could see through the window that a larger crowd had gathered outside, and its colourful banners swayed as it moved.

I could see through the window that a larger crowd had gathered outside, and its colourful banners swayed as it moved.

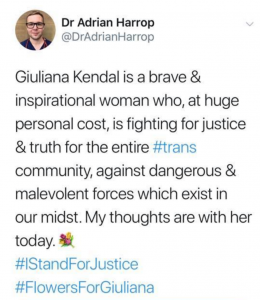

There are those, of course, who think the whole thing was a wonderful idea.

There are those, of course, who think the whole thing was a wonderful idea.

After we’d been waiting for about ten minutes, a chant of “self defence, no offence” broke out before turning to cheers and clapping as Linda and Venice joined us. Huge smiles broke out on their faces as they hugged those who had come out to support them. One group of women broke into a chorus of “there’s only one Venice Allan” and others took photos of and with the defendants. Linda made a rousing speech, but I missed what she said. Luckily, it was recorded and you can see the video on YouTube

After we’d been waiting for about ten minutes, a chant of “self defence, no offence” broke out before turning to cheers and clapping as Linda and Venice joined us. Huge smiles broke out on their faces as they hugged those who had come out to support them. One group of women broke into a chorus of “there’s only one Venice Allan” and others took photos of and with the defendants. Linda made a rousing speech, but I missed what she said. Luckily, it was recorded and you can see the video on YouTube