Jess de Wahls grew up in East Berlin. She now lives in London where she has been nicknamed ‘the enfant terrible of the textile industry’. Her work features detailed patches weaving together feminism and plant life as well as complex larger pieces, many of which can be seen on her website here.

Jess de Wahls grew up in East Berlin. She now lives in London where she has been nicknamed ‘the enfant terrible of the textile industry’. Her work features detailed patches weaving together feminism and plant life as well as complex larger pieces, many of which can be seen on her website here.

In 2018 the craft council ran a story about her work. You can read it here.

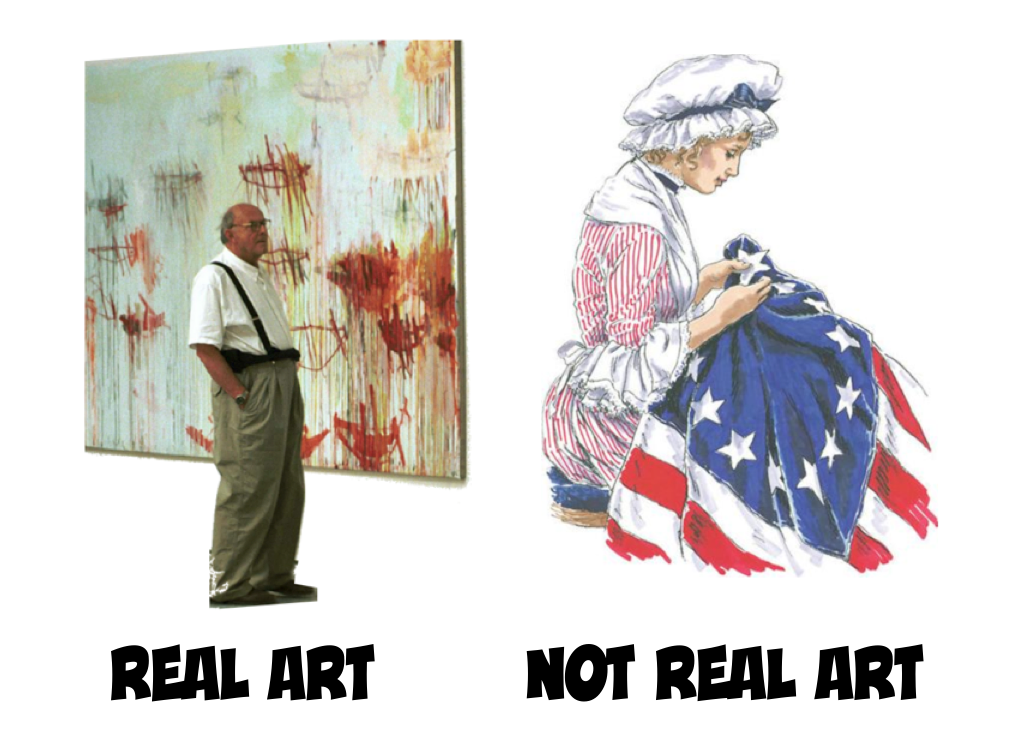

The first time I saw Jess’s work was at the Knitting and Stitching Show in London, in early 2017. You may not imagine that the Knitting and Stitching Show would be a particularly exciting place but you would be wrong. Textiles are frequently derided and  perceived as somehow secondary or ‘not real art’ and a moment’s contemplation will reveal why.

perceived as somehow secondary or ‘not real art’ and a moment’s contemplation will reveal why.

The knitting and stitching show is a giant arts and crafts meet up, sporting spectacular fabrics, hand spun yarns, bijou buttons and an array of wonderful art. There is also coffee and cake, albeit somewhat overpriced. The thousands who pass through it’s doors each year are, I’d guess, about 95% female, so there is a strange sense of freedom and camaraderie knowing that you’re in the company of so many other arty women.

On this particular day I turned a corner and was struck by a small but perfectly embroidered rainbow spanning a womb and ovaries, framed and mounted on a large white wall. The colours, accuracy and detail of the work was exquisite.

“I love that,” I said to my mum, looking over the other stuff on display. ” I want to talk to the artist.”

Having ascertained that the artist was present, I approached her, a striking young woman who gave me a huge smile, and then I realised I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to say.

“I love your work,” I offered, with stunning originality. When she thanked me I added, rather awkwardly and obviously, “It’s feminist.” She nodded.

I think I asked if I could take a photo and she said yes.

Later, a friend and I blew up part of that photo and stuck it on a banner adorned with ribbons which we held proudly aloft on the 2017 Women’s March in London.

Later, a friend and I blew up part of that photo and stuck it on a banner adorned with ribbons which we held proudly aloft on the 2017 Women’s March in London.

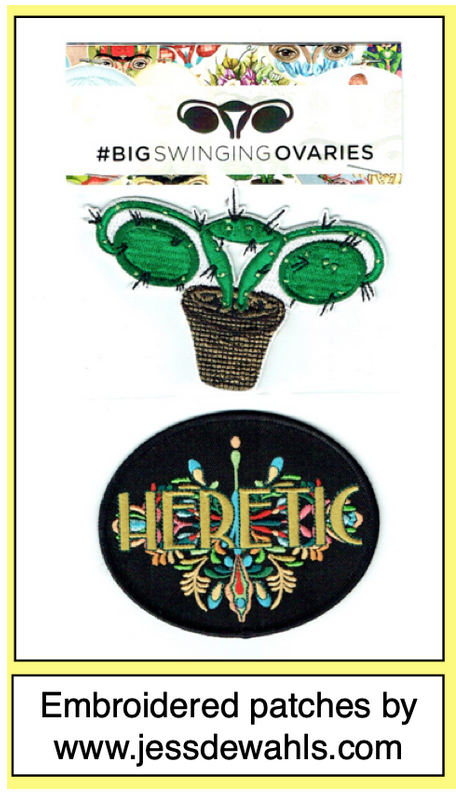

The next time I saw de Wahls was at the Women’s Liberation Conference in 2020 where she had a stall featuring and selling some of her embroidery. I bought two of her patches.

The next time I saw de Wahls was at the Women’s Liberation Conference in 2020 where she had a stall featuring and selling some of her embroidery. I bought two of her patches.

They sat in my needlework box for a while until a few months ago when I ironed ‘heretic’ onto the bodice of a tie-dyed dress. I was wearing it yesterday when I saw that Jess was in the news.

The ‘heretic’ patch on her website is currently sold out, but you can pre-order one here.

I’m told that just eight complaints about the views of Jess’s views were made to the Royal Academy (RA) but at the time of publication this has not been confirmed.

I’m told that just eight complaints about the views of Jess’s views were made to the Royal Academy (RA) but at the time of publication this has not been confirmed.

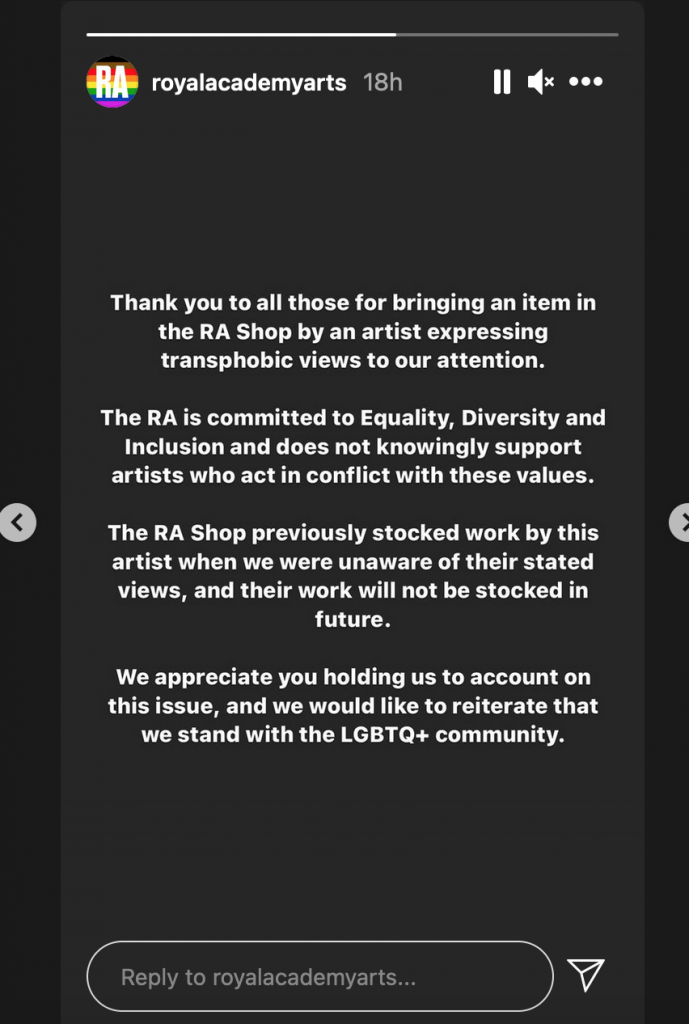

The Academy (currently sporting the awful flag which implies that gay people were previously not inclusive of people of colour) has issued a statement saying it will no longer stock her work in their shop due to her ‘transphobic’ views. On their Instagram story they posted this statement:

“Thank you to all those for bringing an item in the RA shop by an artist expressing transphobic views to our attention. The RA is committed to Equality, Diversity and Inclusion and does not knowingly support artists who act in conflict with these values. The RA shop previously stocked work by this artist when we were unaware of their stated views, and their work will not be stocked in future. We appreciate you holding us to account on this issue and we would like to reiterate that we stand with the LGBTQ+ community.”

It is interesting to note that the RA’s policy on Equality and Diversity has added ‘gender, gender identity or expression’ to the Equality Act’s list of protected characteristics. It has not removed sex, although its willingness to view de Wahls’ view that a woman is an adult human female as ‘transphobic’ suggests that this is not much more than lip service.

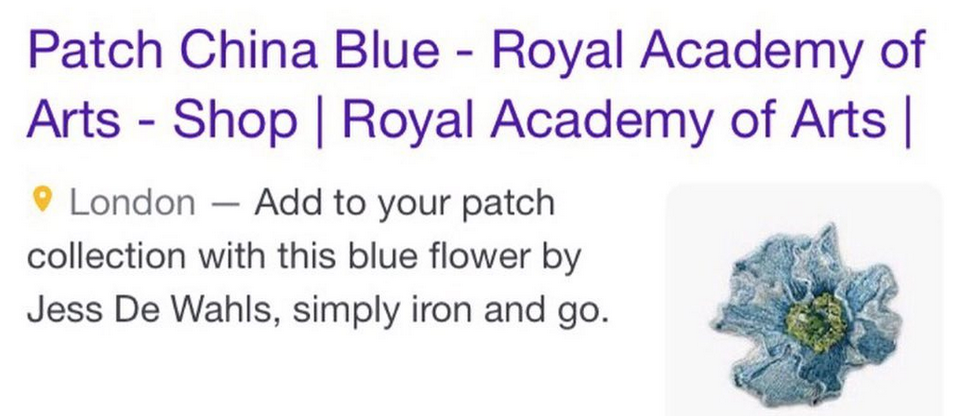

What was the piece stocked by the RA gift shop before it was so hurriedly removed, I hear you ask? Are you sure you’re ready for this?

Nothing less than a blue embroidered flower. Avert your eyes lest ye should receive the full force of its transphobic hatred. Those trying to find it via the RA website are now are met with this notification:

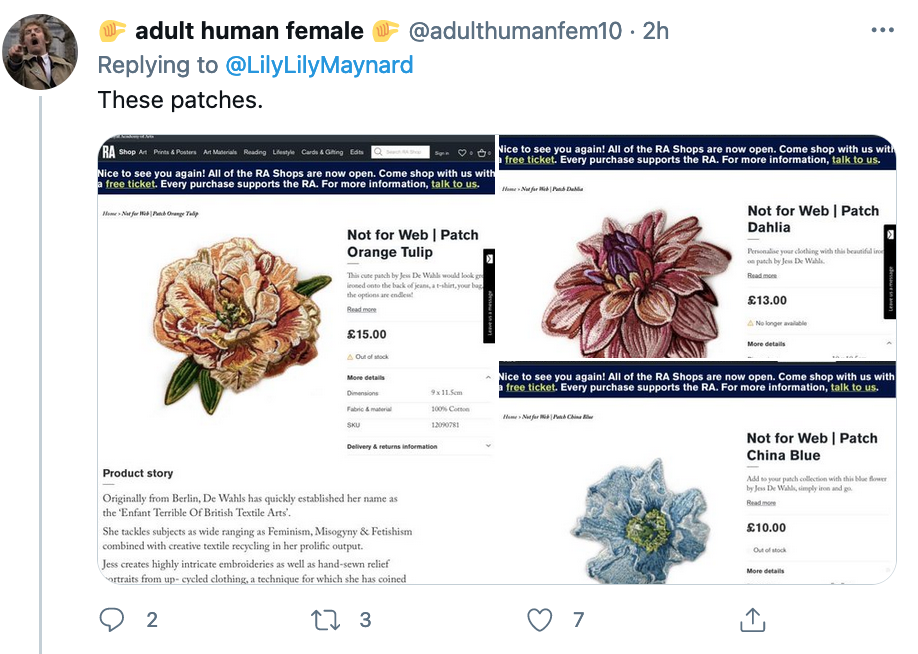

A search by @adulthumanfemale also suggested that two more of de Wahls flowers had been in stock and had been removed by the RA.

A search by @adulthumanfemale also suggested that two more of de Wahls flowers had been in stock and had been removed by the RA.

Are we surprised? Well, probably not, to be honest. These days a mere whisper of ‘transphobia’ is enough to bring entire civilisations to their knees. And the Royal Academy, like so many great British institutions, does not have a glowing history of supporting equality of the sexes.

Laura Herford

The RA was founded in 1768. Despite two of its founding members being women, the painters Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffman, the first female student, Laura Herford, was only admitted in 1890, and that was by accident after she submitted work signed only with her initials. Pretty sure nobody asked her how she identified.

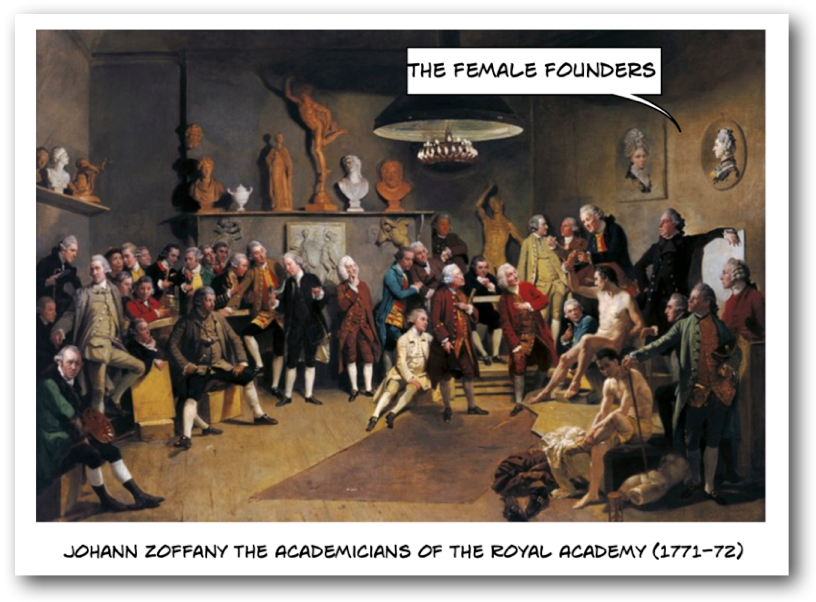

Johann Zoffany’s 1771/2 painting, The Academicians of the Royal Academy, shows the blokes getting ready for a life drawing class- the female founders are just pretty pictures on the wall. It wasn’t until 1967 that the then-four female Academicians were invited to dine with the lads. But of course, there’s nothing surprising about such sexism.

Nobody’s quite sure why the women didn’t just identify out of it, silly, feather-brained little things. But I digress.

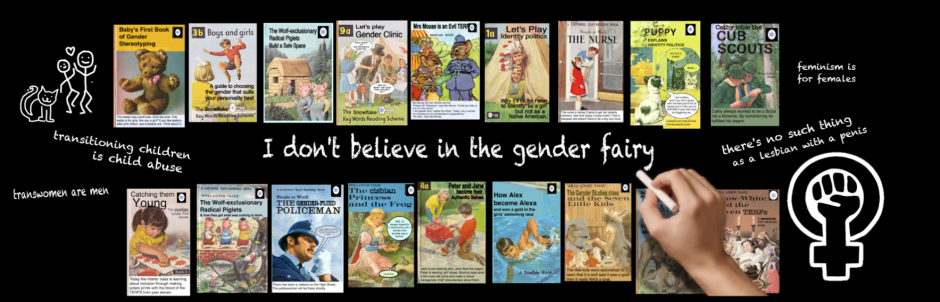

The awful, oppressive and dangerous nature of de Wahls’ opinions and work was brought to the attention of Instagram by fellow embroidery artist Jessica So Ren Tang (she/her) who told 48K followers:

“WARNING:TRANSPHOBIA Seems like some folks need a run down that supporting Jess De Wahls means supporting a Trans exclusionary radical feminist, aka TERF, aka transphobe… for @royalacademyarts to purchase work by De Wahls, an openly transphobic artist, during Pride whilst using a pride flag on their profile picture is grossly rainbow washing.“

This is not the first time de Wahls has been on the receiving end of such attacks from Jessica.

Back in September 2020 Jessica posted about having given £550 to Mermaids because “I am vocal about trans rights and my general disappointment with Jess De Wahls… It’s disgusting to see de wahls profiting off of transphobia… Of course, this (donation) doesn’t erase transphobia but it’s something I can do.”

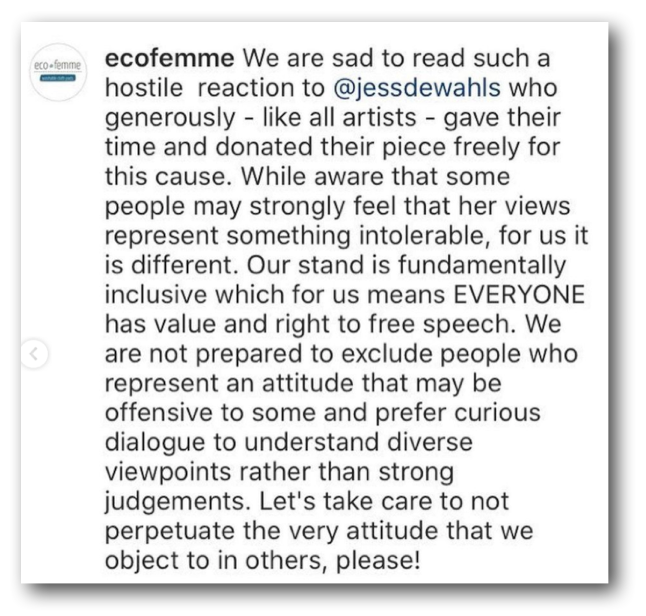

As far back as 2019 Jessica attempted to get de Wahls removed from an art project designed to provide support for menstruation supplies to girls in India. The organisation refused to drop de Wahls, commenting that “her art piece… is not offensive to anyone”.

As far back as 2019 Jessica attempted to get de Wahls removed from an art project designed to provide support for menstruation supplies to girls in India. The organisation refused to drop de Wahls, commenting that “her art piece… is not offensive to anyone”.

You keep throwing mud, as my old gran used to say and eventually some of it sticks. The call out to Jessica’s followers resulted in a handful of complaints to the Royal Academy, and that was enough.

For those interested in knowing more about De Wahl’s evil transphobic views, look no further. In 2019 she wrote the piece ‘somewhere over the rainbow something went terribly wrong’ in which she states, “I feel no animosity towards people who hold different beliefs to me, be they religious, gender identity ideology or any other kind of faith, and I hope you can extend the same courtesy to me,” going on to add “Humans can not change sex. If we ignore sex, we ignore sexism. This is important, particularly for women, living in sexist societies.”

Jess also makes it clear that she is very close to her father who, as you will see if you read the article, is about as ‘gender non-conforming’ as you can get. The piece is detailed, thoughtful and brilliant and I highly recommend you read it.

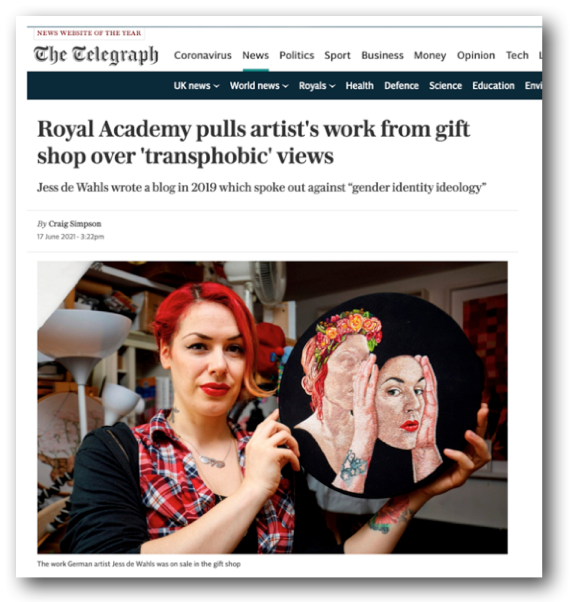

The current controversy was featured in today’s Telegraph, where writer Craig Simpson pointed out that “prints of the work of Paul Gauguin, who reportedly had had sexual relationships with a succession of young girls, were sold during the 2020 exhibition Gauguin and the Impressionists.”

The current controversy was featured in today’s Telegraph, where writer Craig Simpson pointed out that “prints of the work of Paul Gauguin, who reportedly had had sexual relationships with a succession of young girls, were sold during the 2020 exhibition Gauguin and the Impressionists.”

This raises the issue of the long-running debate on how, if and when we separate the art and the artist. That we should even be expected to consider a connection between de Wahls’ view that sex is immutable and the actions of an active paedophile is quite astonishing.

If the work of De Wahls is unworthy of respect due to her view that it’s not possible to change sex and that gender ideology is harmful, who is above reproach?

“Hi@royalacademy. Can you tell me when you will be removing all the work of Eric Gill?” asked @Delilahinboots on Twitter. “I mean, I know he didn’t do anything really bad like misgendering, but he did assault and abuse his own daughters, and his dog. As we now only care about artists views, not the art, it’s time?”

Delilah goes on to add, “think you have a Caravaggio or two on display? Again, murdering and castrating a rival not in the realms of horrific crime like say, depicting actual women in embroidery, but still, not something you want to be seen to be supporting.”

Maya Forstater, whose recent case established gender critical beliefs to be a protected characteristic under the Equality Act, called the response an ‘overreaction’ and told the Telegraph, “They (the Royal Academy) need to take a deep breath, look at the Equality Act and consider that everybody has rights. These coordinated complaints ruin people’s lives and their reputations and make organisations fearful. It is Mccarthyism and many people are afraid.”

Sex Matters reports: “This is belief discrimination, and breaches Jess Wahls’ rights under the Equality Act and the European Convention on Human Rights. We have written to the Royal Academy, and to the Charity Commission and the Heritage Lottery Fund that support them to raise the issue and to highlight Jess Wahls’ human rights which they have ignored in their rush to appease the mob.”

You can contact the Royal Academy via this link.

So while we wait for an apology from the RA- which is unlikely to be forthcoming unless they are threatened with legal action- pop along to Jess’s website and treat yourself.

Her website is here, although her work is selling out fast. Jess is undaunted.

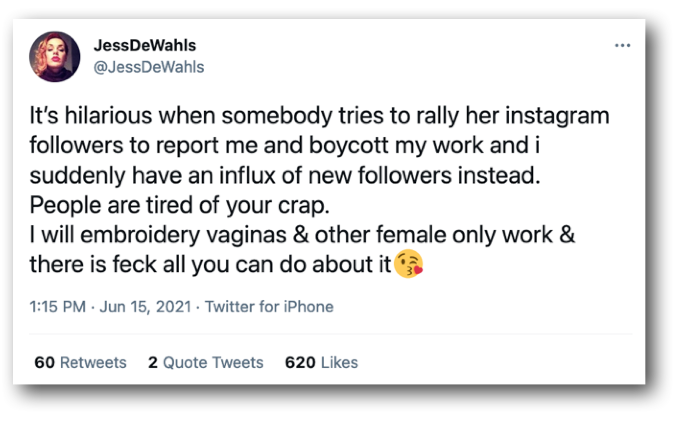

“I will embroidery vaginas & other female only work & there is feck all you can do about it,“ she wrote on Twitter on June 15th.

Big swinging ovaries indeed.

UPDATE 23/6/21

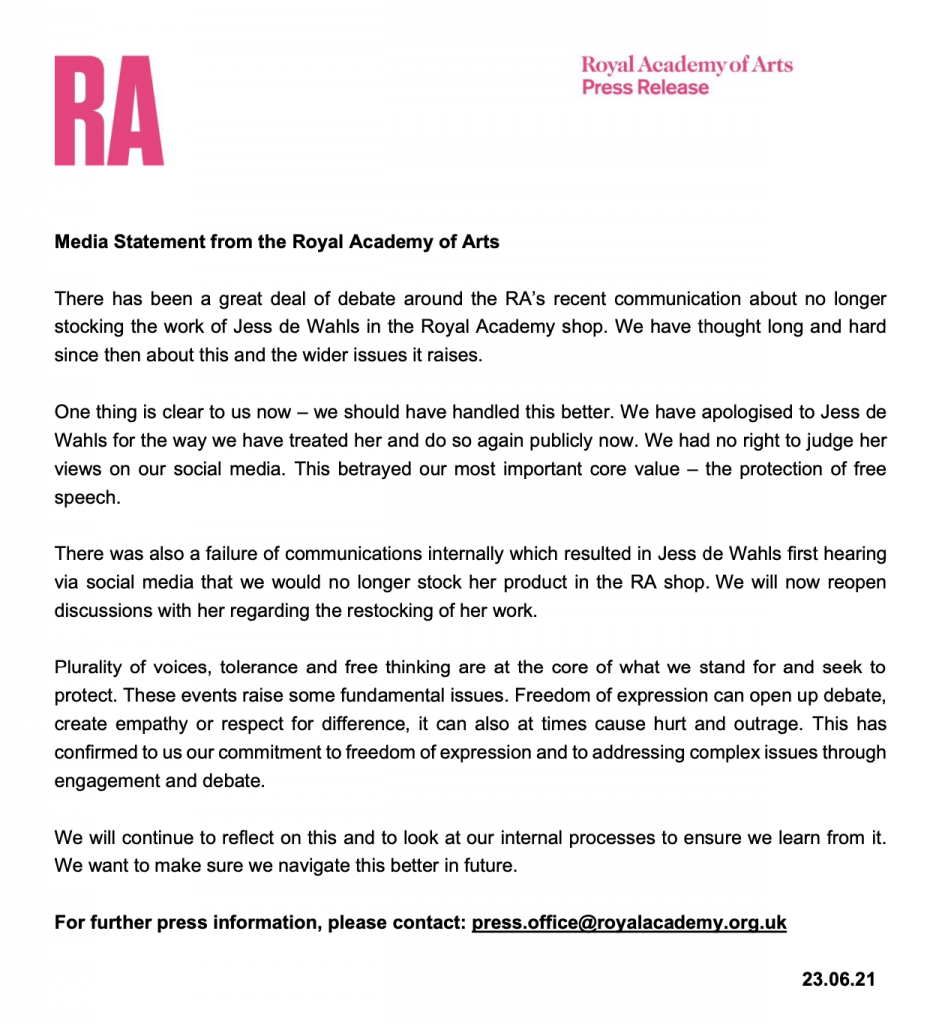

We were today greeted with a press release, giving us the news that the Royal Academy has issued an apology to Jess de Wahls. Here it is, in all its glory.

Media Statement from the Royal Academy of Arts:

“There has been a great deal of debate around the RA’s recent communication about no longer stocking the work of Jess de Wahls in the Royal Academy shop. We have thought long and hard since then about this and the wider issues it raises.

One thing is clear to us now –we should have handled this better. We have apologised to Jess de Wahls for the way we have treated her and do so again publicly now. We had no right to judge her views on our social media. This betrayed our most important core value –the protection of free speech.

There was also a failure of communications internally which resulted in Jess de Wahls first hearing via social media that we would no longer stock her product in the RA shop.We will now reopen discussions with her regarding the restocking of her work.

Plurality of voices, tolerance and free thinking are at the core of what we stand for and seek to protect. These events raise some fundamental issues. Freedom of expression can open up debate, create empathy or respect for difference, it can also at times cause hurt and outrage. This has confirmed to us our commitment to freedom of expression and to addressing complex issues through engagement and debate.

We will continue to reflect on this and to look at our internal processes to ensure we learn from it. We want to make sure we navigate this better in future.

For further press information, please contact:[email protected]

23/06/21

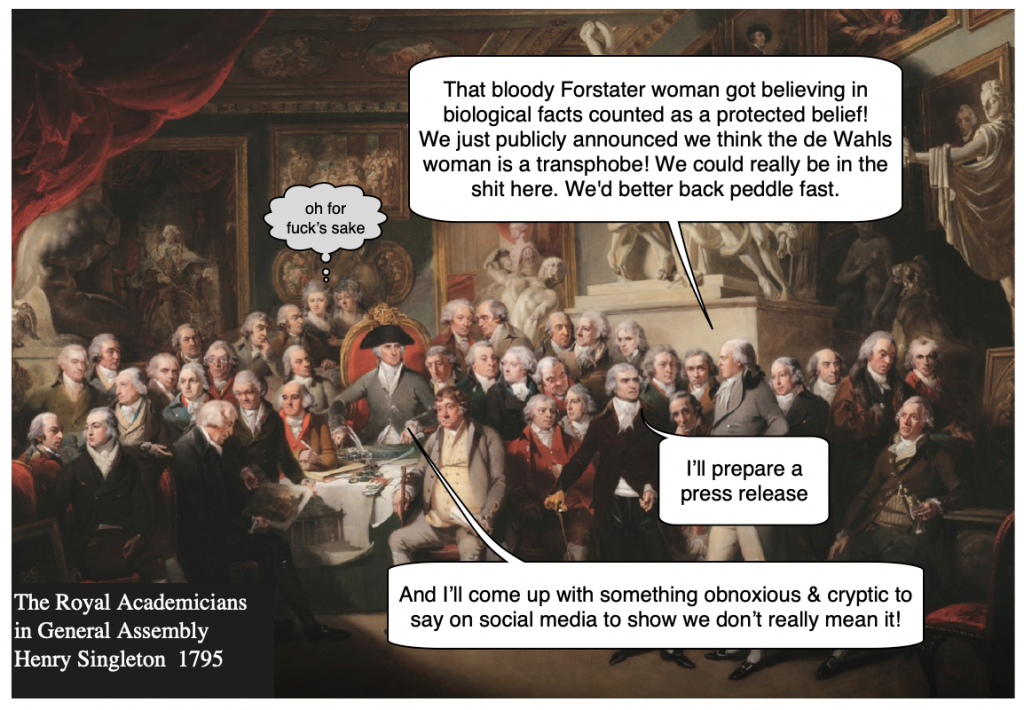

Of course the RA has thought long and hard about this.

It has certainly thought long and hard about the implications of the recent Forstater v CGD case, which concluded that gender critical beliefs are worthy of respect in a democratic society.

It thought about how it had just publicly called de Wahls a ‘transphobe’.

Maybe the RA really is sorry. Or maybe it thought,

“We could really be in the shit here. We’d better backpeddle fast.”

The apology? Did they mean it? It would be nice to think so. Or by ‘we should have handled it better’ did they mean ‘we wish we hadn’t got caught out and had to say sorry’?

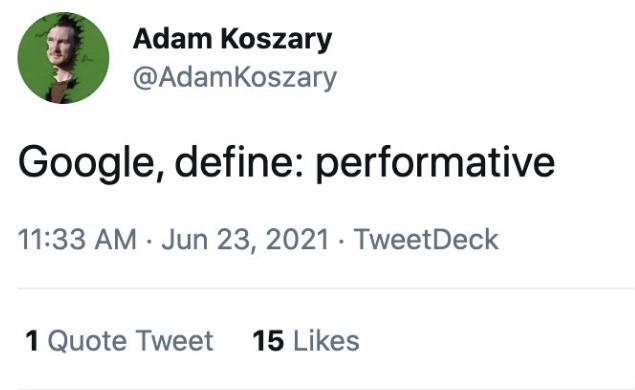

The latter view of the situation seems to have been confirmed by Adam Koszary, Manager of Social Media & Editorial Content at the Royal Academy. Shortly after the press release was published on the RA website, Kaszary tweeted this:

“Google, define: performative”

I have to say, I admire his presentation. The powerful punctuation rounded off by the omission of the oh-so-dated full stop. It’s almost poetic. But that’s this man’s job. He co-ordinates social media for the RA, and sets up the strategy for editorial content. Does his tweet has the approval of the higher echelons of the RA? Who knows?

Either way, you can bet he felt pretty damn pleased with himself when he pressed that ‘tweet’ button.

But surely nobody’s surprised at Adam‘s little strop, masquerading as wit. We know the apology was performative! We all know the RA aren’t really sorry.

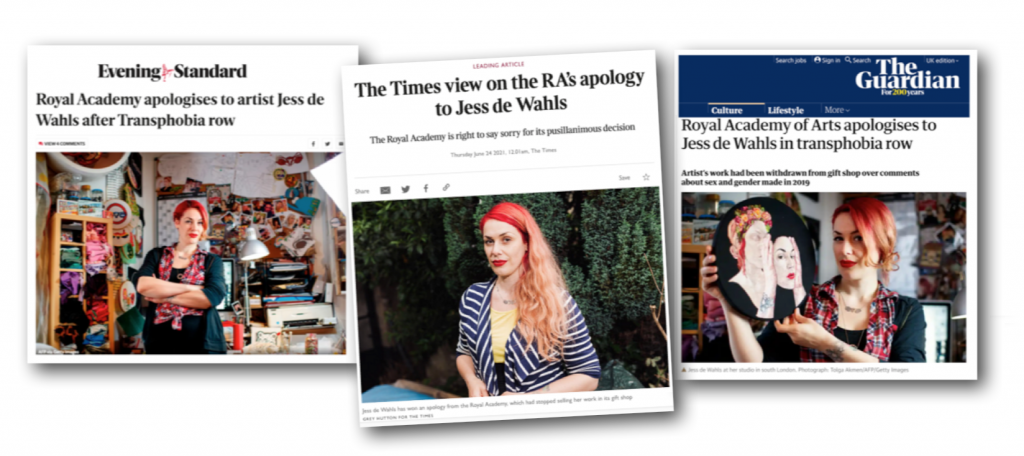

The Times calls the RA’s statement ‘welcome’ as it called the original decision to ‘cancel’ Jess ‘pusillanimous’ and speculated as to “why the academy ever imagined that suppressing a conscientious and thoughtful point of view was its prerogative”.

“The academy had been accused of breaching the Equality Act by removing from sale the embroidered flowers by Ms de Wahls.” reported the Standard.

“I think it’s important for an institution like that to stay out of these things,” de Wahls told the Guardian. “I hope that all the other institutions are watching, and learn a lesson. I hope this brings it back to a place where disagreement can happen without assuming hate.”

So yes, Adam Koszary did get in his snidey little tweet – but the RA did have to apologise to Jess de Wahls, and that’s the win.

Google ‘bad loser’, Adam

De Wahls believes the apology to have been genuine, and perhaps she’s right.

As she has pointed out, she’s the one who was talking to them.

I hope she’s right.

A

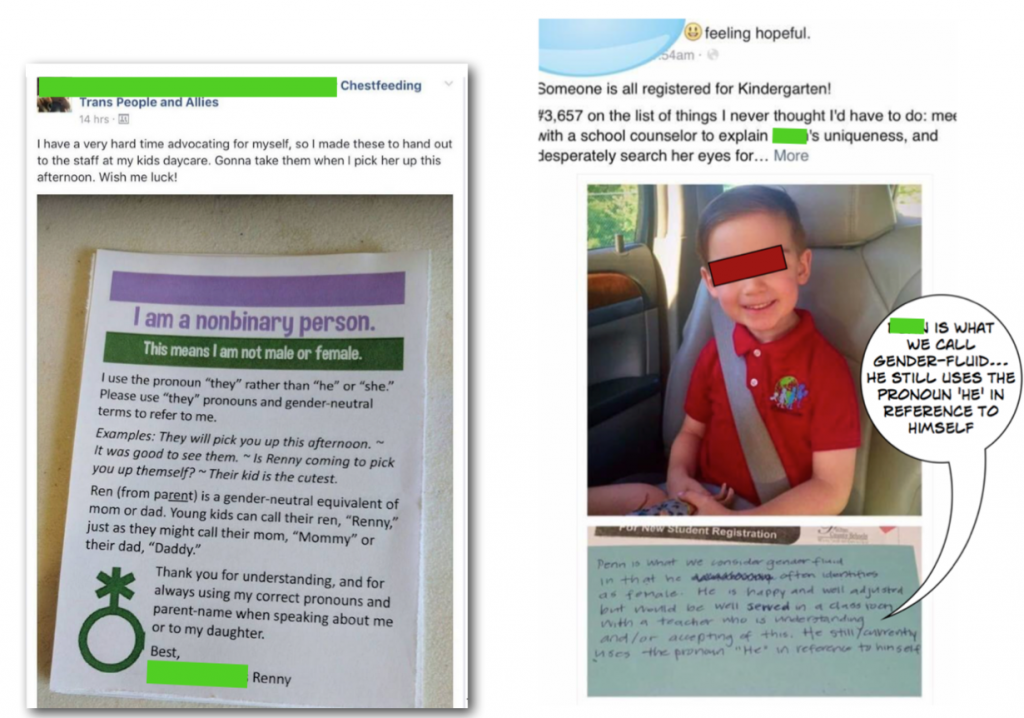

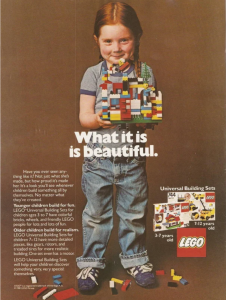

A

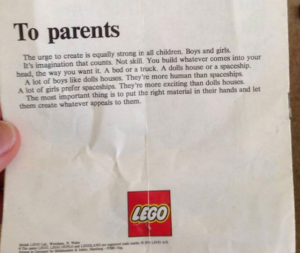

Lego has recently released an ‘everyone is awesome’ box set for Pride 2021. It features mini figures in the pink blue and white colours which are now the symbols of the trans movement – white symbolises the enbys. There the figures are, all lined up in a neat little row. If the kids don’t like stereotypes, there’s another box they can fit themselves into.

Lego has recently released an ‘everyone is awesome’ box set for Pride 2021. It features mini figures in the pink blue and white colours which are now the symbols of the trans movement – white symbolises the enbys. There the figures are, all lined up in a neat little row. If the kids don’t like stereotypes, there’s another box they can fit themselves into. Yes, Lego, probably the 20th century’s most inclusive toy- now celebrates the idea of the Enby.

Yes, Lego, probably the 20th century’s most inclusive toy- now celebrates the idea of the Enby.

The

The  “A new teaser of the upcoming Disney+ series, Loki, has confirmed that the God of Mischief is part of the gender-fluid community!” gushed International News this week (June 2021), in a short article headlined ‘Loki’s non-binary identity confirmed in new Disney+ teaser’.

“A new teaser of the upcoming Disney+ series, Loki, has confirmed that the God of Mischief is part of the gender-fluid community!” gushed International News this week (June 2021), in a short article headlined ‘Loki’s non-binary identity confirmed in new Disney+ teaser’.  Now I’m all for ‘cannon’ and I am a massive comic book fan. I made myself highly unpopular on social media recently by trying to explain to a group of feminists who had never read the series that Desire in Sandman was literally non-binary.

Now I’m all for ‘cannon’ and I am a massive comic book fan. I made myself highly unpopular on social media recently by trying to explain to a group of feminists who had never read the series that Desire in Sandman was literally non-binary.

Perhaps we should start a middle-aged non-binary revolution. After all, the best way to get kids to stop doing something they think is cool and edgy is for the grown ups to start doing it too. The older the better! After all, ageism is the last -ism that is still culturally acceptable.

Perhaps we should start a middle-aged non-binary revolution. After all, the best way to get kids to stop doing something they think is cool and edgy is for the grown ups to start doing it too. The older the better! After all, ageism is the last -ism that is still culturally acceptable. The homepage asks the question ‘Am I neutrois?’ with the quick reply:

The homepage asks the question ‘Am I neutrois?’ with the quick reply: