Recently there has developed a fashion for rewriting the lives of certain non-conformist women to claim them as transgender. Joan of Arc, Jennie Hodgers, James Barry; even Queen Elizabeth I has not escaped the suggestion that the wearing of men’s clothing or living a lifestyle usually inaccessible to women was the result of such a brain/body mismatch, almost as if to suggest that women really are incapable of such achievements unless they ‘identify’ as men.

Recently there has developed a fashion for rewriting the lives of certain non-conformist women to claim them as transgender. Joan of Arc, Jennie Hodgers, James Barry; even Queen Elizabeth I has not escaped the suggestion that the wearing of men’s clothing or living a lifestyle usually inaccessible to women was the result of such a brain/body mismatch, almost as if to suggest that women really are incapable of such achievements unless they ‘identify’ as men.

Whatever the reason these women wore men’s clothing or chose to present as male, the fact remains that they were women: often lesbian or bisexual women, women who stepped out of line, women who wouldn’t play the role men demanded they play, women who took on a male identity to protect themselves against rape, to fulfill academic or personal ambition, or for love.

To claim that these women were actually men is an insult to every female who has ever experienced exasperation with the confines of a world that tells her ‘no’, from the little girl not allowed to climb a tree to the would-be surgeon who had to hide her sex all her life.

They are our wild women.

We need them;

future generations of girls need them,

and NO, YOU CAN’T HAVE THEM.

It’s easy to forget how far we’ve come in such a short time and how few options were open to the women before us.

The Brontë sisters, by Sir Edwin Landsee

Take literature. The Brontë sisters felt obliged to publish their work under male pseudonyms in 1846. Mary Ann Evans published her novel Middlemarch in 1871 under the name George Eliot. We like to think things have changed, yet 126 years later Joanne Rowling published the ‘Harry Potter’ series using the initials JK as her publishers thought, so her website blithely and unashamedly tells us, “a book by an obviously female author might not appeal to the target audience of young boys.”

I recently bought the Penguin Classic ‘English Romantic Verse’ which is one of the most popular poetry texts for this year’s Edexcel ‘A’ level syllabus. It contains 340 pages of verse by male poets. At the end of the book there are just eight pages given over to verse by Emily Brontë. No other woman features. Another text used by the same board, ‘The Great Modern Poets’ contains just seven women out of fifty selected poets.

So. Possibly we haven’t come so very far after all.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, c.1888

Take medicine. Elizabeth Garret Anderson qualified as a doctor in England in 1865 via a legal loophole which was immediately closed behind her. She had to start her own practice because as a woman, she was not allowed to practise in a hospital. Frances Hoggan qualified as a doctor in 1870- but only by getting her degree from a Swiss University, where she completed the six-year course in three years, going on to specialise in women’s and children’s diseases. Prior to this the only woman to qualify was Margaret Ann Bulkley who was obliged to change her name to James Barry and attend university as a man in order to qualify as a doctor in 1812 – she went on to perform the first successful Caesarian section in Africa. (More on her later.) It was 1880 before the first few women were awarded a BA degree by a British university.

Thank goodness that’s all changed, right? Well, yes and no. Although in 2016 a huge 58% of students accepted on to medicine courses were women, just 11% of consultant surgeons in England were female. Across Britain as a whole, there are still nearly twice as many male registered doctors as female.

Let’s have a look at some more ‘firsts’ for women in the UK, using examples from more recent times.

1914 – Edith Smith became Britain’s first female police officer with powers of arrest.

1919 – Constance Markievicz became the first woman elected to the House of Commons.

1922 – Ivy Williams became the first woman called to the bar.

1956 – Rose Heilbron became the first woman judge.

1976 – Mary Langdon became the first female fire fighter.

1979 – Margaret Thatcher became Europe’s first female elected head of state.

1991 – Helen Sharman became the first female British astronaut

1992 – Betty Boothroyd became first female Speaker of the House of Commons

1995 – Pauline Clare became the first female chief constable.

2001 – Clara Furse became the first woman CEO of the London Stock Exchange

2002 – Carolyn Kirby became first female President of The Law Society.

2006 – Margaret Becket was the first woman to become Foreign Secretary.

2009 – Carol Ann Duffy became the first female poet Laureate.

2012 – Sarah West became the first woman to command a warship in the Royal Navy.

2015 – Libby Lane became first female Bishop to the Church of England.

2017 – Cressida Dick became first female Commissioner to the Metropolitan Police.

2018 – Minette Batters became the first woman President of the National Farmers Union.

Why do you think women weren’t doing these jobs and reaching these positions of influence and power earlier? Was it because of their innate sense of gender identity? A sort of inner knowledge that these professions were perhaps not becoming to a real lady? Was it because they just didn’t want to? I think it’s pretty fair to assume that women were not achieving these things because men stopped them- and that men stopped them because of their female bodies, not because of their inner sense of gender. That men stopped them because they were women.

For most women it was impossible or impractical to overcome this hurdle. Some had no desire to do so and that’s fair enough. For others, like the Brontë sisters, and Mary Ann Evans it needed anonymity and a name change. As Evans said, “The important work of moving the world forward does not wait to be done by perfect men.”

But for those who wanted to fight battles, live openly with other women, feed their families in times of poverty or enter male-only professions there was only one possibility. Masquerade as a man.

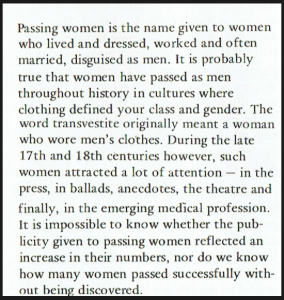

At the Feminist Library Christmas Fair in December, I was lucky enough to purchase a 1985 copy of the feminist magazine ‘Trouble and Strife’, containing Lynne Freidli’s article ‘Women Who Dressed as Men – Cross Dressing in the 18th century’.

Lynne Freidli – Women Who Dressed As Men

In it she observes that there were usually three categories of ‘passing women’, the rich eccentric (exempt from prosecution due to class), the soldier or sailor (often given an honourable discharge if discovered) and the lower class women who ‘lived, worked and often married as men, and if discovered were variously punished by imprisonment and whipping or pilory’. One such was the unfortunate Mary Hamilton, who was convicted of fraud after marrying a woman. She was first imprisoned, then ‘publicly whipped in four towns’ before being released.

Hannah Snell

Hannah Snell- ‘drawn from life’ by I.P. Boitard

In the 1740s, after her marriage broke down and her baby died, Hannah Snell from the English West Midlands renamed herself James Gray, disguised herself as a man and served in the exclusively-male Royal Navy for four years. When shot in the groin in the battle of Pondicherry, she dug the bullet out herself rather than be exposed. On return to England after the war she became semi-famous, appearing in theatres and singing patriotic songs on stage. She managed to persuade the army to give her a pension, and when she died in Bedlam age sixty nine, she was buried with the other soldiers at Chelsea Hospital.

She was certainly not the first woman to follow this path. So many women disguised themselves as men in order to fight in the British civil wars of 1639-51 that King Charles I issued a proclamation banning women from wearing men’s military clothing.

“In 1645, Oliver Cromwell, then a lowly second in command, captured a royalist aristocrat, Lord Henry Percy, and a group of supporters. Cromwell noted “a youth of so faire a countenance, that he doubted of his condition; and to confirm himself, willed him to sing” – which the prisoner did “with such daintiness” that her true sex was revealed.”

It wasn’t until 2018 that the British army opened all combat roles to women.

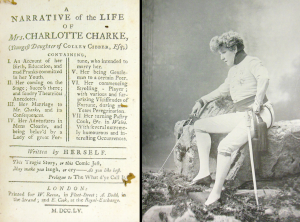

Charlotte Charke

Charlotte Charke of London, youngest of 12 children, worked primarily as an actor and playwright but also dabbled as a pastry cook, a pub owner and a hog merchant, among other professions. In the introduction to Charke’s 1755 autobiography ‘A Narrative of the Life of Mrs Charlotte Charke’, she promises the reader tales of “her adventures in men’s clothes, going by the name of Mr. Brown, and being beloved by a lady of great fortune, who intended to marry her.”

“From her earliest memories, Charlotte’s passions centered around riding, shooting, and emulating the males around her.” writes history blogger lifetakeslemons. “At age four, she had already cultivated an attachment to periwigs and male dress, stealing her brother’s and father’s clothes to strut in a ditch and bow to passersby.”

Charlotte married in her teens, reflecting that she ‘be(came) a wife before I had the proper understanding of a reasonable child.” Her husband, a gambler, soon fled abroad to avoid debtor’s prison.

Charke was primarily an actor, although also a playwright and she wore men’s clothing on, and later off, the stage. Freidli observes that she was unusual not in rejecting feminine norms but in her ‘determination to live as a man in spite of repeated obstacles and difficulties’. and ‘‘not only explores roles usually exclusive to men, but in doing so mocks the great mystery attached to them’.

Constantly in debt, Charke was estranged from her wealthy father who left her only five pounds in his will. After an action filled life Charke died in poverty, selling her memoir for ten pounds.

Because Charke left an autobiography, it isn’t possible for her to be claimed as a transman and posthumously transitioned. We know that she was quite aware that she wasn’t actually a man. Other women do not have the advantage of a voice from beyond the grave.

There is no doubt that there were many, many more women who disguised themselves as men in order to taste the excitement, challenges and liberty of ‘life as a man’.

“Women who dressed as men had, above all, access to jobs that were limited to males. They enjoyed more freedom of mobility, less fear of sexual attacks, better employment prospects with better pay. They were also free to have sexual relationships with other women and to avoid sex with men… Charging passing women with fraud meant that what was at issue was deception… not sexual practices, but their adoption of a male disguise”

Lynne Freidli

Jeanne d’Arc

Joan of Arc by Albert Lynch (1903)

Reports of the time make it clear that Jeanne adopted ‘men’s’ garb more for practicality in battle and to protect herself against rape, rather than from a inner sense of gender identity. The cords that tied men’s clothing gave a degree of protection which she sorely needed in prison and on the battlefield. One 15th century source recorded ‘“[when she climbs off her warhorse] she resumes her usual feminine clothing”.

While in prison she told a tribunal that her guards had tried to rape her and she didn’t feel safe wearing women’s clothing, saying that if they moved her somewhere she felt safe she was willing to dress as they prescribed. The tribunal made her sign a document stating she would no longer wear men’s clothing.

The trial bailiff remembered that in the end the English guards gave her no other choice but to put the male clothing back on: “When she had to get out of bed… her guards took away the female clothing which she had, and they emptied the sack in which the male clothing was, and tossed this clothing upon her.. they wouldn’t give her anything else… finally, she was compelled by the necessity of the body to leave the room and hence to wear this clothing; and after she returned, they still wouldn’t give her anything else [to wear] regardless of any appeal or request she made of them.”

The same day, the tribunal handed her over to the secular court for her punishment for breaking this rule: burning at the stake.

There is no suggestion in any text that I can find to suggest that Joan believed herself to be a man. Despite this transgender author Leslie Feinberg and many others claim Jeanne as trans.

“It might just turn out that every significant woman in history may have really been a man.” comments Sarah Stuart, wryly, on Twitter.

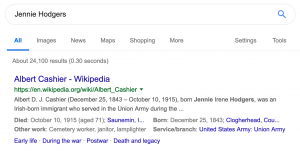

Jennie Hodgers

Google ‘Jennie Hodgers’, an Irish born immigrant who served in the American civil war, and at first sight she seems to be… gone. The first hit you get is for her pseudonym and alter-ego, Albert Cashier and she is celebrated as a brave transgender man.

In her excellent article for Feminist Current, “Jennie Hodgers: A woman who bravely defied sexist norms” Julia Robertson suggests that in refering to Cashier as ‘assigned female at birth’ Adam Gabbatt “instead of celebrating the accomplishments and courage of a woman forced to fight sexist limitations under patriarchy… bolsters a current narrative, taking away one of the few pages women have in history books.”

Jennie Hodgers

More than 400 women disguised themselves as men and fought in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War. Because they passed as men, it is impossible to know exactly how many women soldiers there were. Although both armies forbade women from serving, in 1862, Hodgers joined the Illinois Infantry where she served for three years.

“I am convinced that a larger number of women disguised themselves and enlisted in the service, for one cause or other, than was dreamed of. Entrenched in secrecy, and regarded as men, they were sometimes revealed as women, by accident or casualty.”

Mary Livermore, US Sanitary Commission 1888

At the time, recruits were only required to show their hands and feet at the most basic of medical examinations. After the war was over, Hodgers continued to pass as Albert Cashier, which has been taken by some to affirm her transgender identity. Robertson disputes this, observing that “unable to read or write, (Jennie) had passed as Albert in order to survive and work in fields she would not have been permitted to otherwise, as a woman. “

Hodgers’ secret was not discovered until she developed advanced dementia and was hospitalised.

““Unused to walking in the long, cumbersome garments deemed appropriate for her sex, she tripped and fell, breaking a hip that never properly healed. Bedridden and depressed, her health continued to decline, and she died on Oct. 11, 1915.”

Women in Trousers

The reasons women had for choosing to represent themselves as men have traditionally been based on the restrictions placed on them: not so much that they believed themselves to be men but that they believed they should be entitled to the same freedoms as men. To attempt to take those freedoms was likely to result in rape, incarceration or punishment. There is a chasm between the two ideas. One suggests that women should stay in their lane, that they belong there and that deviation from this norm is somehow a renunciation of womanhood. The other suggests that women can achieve… well, pretty much anything given the right circumstances.

Helen Hulick

It does seem astonishing that men would be so incredibly threatened by the idea of women wearing trousers. Yet in 1938 America, when 28 year old Helen Hulick, a witness to burglary, repeatedly showed up in court in trousers despite being ordered not to by a judge, he held her in contempt of court. She was given a five-day sentence (which she did not serve) and sent to jail.

But 1938 was ages ago, right? Things have changed, right? Maybe not so very much.

In 2018, Roberta Borsotti finally persuaded her daughter’s school to let the child wear trousers, but only after she threatened legal action.

“She now says she feels less worried about running around,” said Borsotti. “Before she was thinking more about what she was doing because the dress might get caught in something. She feels more free now.”

Borsotti is now bringing a legal challenge against the government’s uniform guidance, which she says is discriminatory. There are still plenty of schools in Britain which insist on girls wearing skirts or dresses to school, despite the concerns of many lawyers that this contravenes the Equality Act.

‘Trousers are smart and practical for the rigours of school life and there is no reason for girls to be prevented from wearing them. It’s vital that we encourage young people not to be limited by old-fashioned, stereotypical ideas on men and women’s roles in society, and dress codes play an important part in how we see ourselves.’

EOC Chairwoman Julie Mellor

However, one of the biggest reason for this change in policy seems to be to accommodate transgender students. It’s not so much the feeling that girls should be allowed to wear comfortable clothing, but that girls who are actually boys should be allowed to do so.

When Priory School in Essex changed its uniform policy to address ‘the current issues of inequality and decency’ after ‘a number of complaints about short skirts’, they decided to ban skirts altogether, starting with Year 7.

The Daily Mail reported that “teachers say the new attire is being imposed to stop girls dressing provocatively and to help the ‘small but increasing number’ of transgender pupils at the school.”

Headteacher Tony Smith told the Independent, “.. having the same uniform is important for them (transgender pupils).”

The BBC reports that Welsh Government guidance suggests “clothing choices should not be based on sex or gender, and flexibility is urged to help pupils undergoing gender reassignment.”

If it seems that I’m going a little off-topic, consider this. Not much has changed at all. Young girls wearing skirts is viewed as ‘provocative’ and uniform changes are been brought in, not out of consideration for girls but to support transgender pupils. Girls, stay in your lane.

Which brings us to a young woman who most certainly didn’t stay in her lane.

James Barry – the story of Margaret Anne Bulkley

“Was I not a girl I would be a Soldier!”

The second child of Jeremiah and Mary-Ann Bulkley was born in Cork, Ireland, in about 1790 and named Margaret Anne.

Margaret had an older brother, John, and a much younger sister about whom little is known. There is speculation that the sister, named Juliana, was actually Margaret’s own child, possibly born as a result of rape by her uncle. Margaret’s father Jeremiah spent time in a debtor’s prison, and her wastrel brother cost the family its little remaining money; after his marriage an impoverished Margaret moved to London with her mother Mary Ann.

“Margaret enjoyed little in the way of prospects and needed to complete her education to earn a living. With no fortune, and from her aspirational middle-class background, marriage would be difficult to achieve, especially as she was ‘unprotected’, having no influential male friend or relative.”

James Barry, Margaret’s uncle, whose name she would later take, is said to have discussed her educational options with friends, including a physician called Dr Edward Frye, and a Venezuelan revolutionary, General Francisco Miranda. Both men helped with her education. When her uncle died he left some money, and her uncle’s friends were each in a position to help her with her academic aspirations: Margaret was interested in a career in medicine but it was not possible for a woman to become a doctor in Britain in the early 19th century. It’s generally held that the General came up with the plan to put Margaret through medical school in Scotland, with a view to having her be part of his new vision for Venezuela, where women were allowed to practice medicine. As only men were allowed to attend medical school, Margaret would need to disguise herself convincingly in order to study. Who knows if it was his idea or Margaret’s? History, as we all know, is ever his-story: perhaps the plan was Margaret’s own, certainly she must have embraced it with enthusiasm in order to take on such a vastly adventurous deception. After all, this was the young woman who at 18 had chastised her wastrel brother in a letter with the words, “Were I not a girl, I would be a soldier!”

” The plan for Margaret’s education had… assumed the dimension of a conspiracy,” observes du Preez “If this construct is correct, the young doctor could have resumed her female identity once qualified and on her way to Caracas, Venezuela.”

“In late November,” writes historian Kathryn Kane, ” Margaret Anne Bulkley rose early one morning, put off her feminine clothing and donned her male garments. Her mother took a pair of shears to her long reddish-blond locks and cut them very short, in the windswept Corinthian style favored by young men of the period. When she peered into the looking glass, Margaret Anne saw James Barry looking back at her. Little did she know that morning, Margaret Anne was gone forever. She would live out the remainder of her life as James Barry, never to wear a skirt or corset again.”

So Margaret began studying medicine in Edinburgh. She was an excellent student. Only around 20% of medical students at Edinburgh at the time actually graduated, and in 1812, Dr James Barry became one of this elite few. There were costs to be paid, oral and written exams to be taken and a thesis to be both written and argued. Everything took place in Latin. This presented little problem for the ever enterprising and inspired Margaret, who pretended she was younger than her actual age in an attempt to explain away her height – she was only 5ft tall- hairless chin, slim build and high voice.

Unfortunately, around the time Margaret graduated General Miranda was betrayed and defeated, imprisoned until he died, and Margaret’s plans of practice in Venezuela were abandoned. Faced with the prospect of remaining in England, Margaret was left with a tough choice. Reveal herself to be a woman and face the consequences, or continue to masquerade as a man. She chose the latter, pulling it off brilliantly for over half a century. Thereafter she was to be known as Doctor James Miranda Steuart Barry, a tribute to both the uncle who funded her education, and the General who helped fulfill her dream.

After working briefly at Guys and St Thomas’ hospitals. Dr James Barry joined the army, which raises the question of how Margaret managed to pass the medical examination without her sex being discovered.

“Rutherford” writes du Preez “offers the credible explanation… that the new recruit had presented letters from an eminent surgeon and a well- known physician to confirm that he was in good health, thereby avoiding the routine army physical examination.”

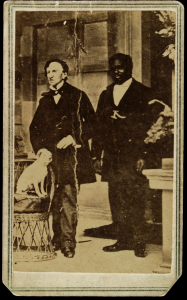

Barry with servant John, and dog Psyche.

Barry was notorious for being a bad-tempered eccentric. Often teased by colleagues for having a high pitched voice, tormentors were challenged to duels and at least one man was shot. Famously, Florence Nightingale was once told off in public by Barry, who she described as “the most hardened creature I ever met throughout the army”.

Yet Barry was also known to be a talented surgeon who treated everyone equally: soldiers and civilians, rich and poor, free men and slaves alive. Known for having an obsession with hygiene, clean water and good ventilation, Barry was ahead of her time in realising the importance of sanitation.

While serving in Cape Town, South Africa, Barry proved her skill by performing one of the first successful Caesarian sections- both mother and baby, named James Barry Munnik in the doctor’s honour, survived. The only remaining portrait of Barry from the time remains in the Munnik family today.

While serving in Cape Town, South Africa, Barry proved her skill by performing one of the first successful Caesarian sections- both mother and baby, named James Barry Munnik in the doctor’s honour, survived. The only remaining portrait of Barry from the time remains in the Munnik family today.

“How fitting that the surgeon was a woman – a woman who had herself once given birth, and was therefore the only surgeon then living who knew first-hand what childbirth was like,”

Jeremy Dronfield.

After Barry’s death

After Barry’s death in 1865, word got out that the famous surgeon had actually been a woman. A representative of the General Register Office wrote to McKinnon, Barry’s doctor, asking why he had named Barry as male on the death certificate. McKinnon did some blustering about how it was none of his business what sex Barry was, and speculated that perhaps she had been a hermaphrodite.

After Barry’s death in 1865, word got out that the famous surgeon had actually been a woman. A representative of the General Register Office wrote to McKinnon, Barry’s doctor, asking why he had named Barry as male on the death certificate. McKinnon did some blustering about how it was none of his business what sex Barry was, and speculated that perhaps she had been a hermaphrodite.

However, McKinnon was honest enough to share a conversation which he had with Sophia Bishop, the woman who cleaned and dressed Barry’s body after her death. The fact that he shared this conversation suggests that while he had been willing to sign that Barry was male on the death certificate, he was not averse to sharing the true story as long as his own back was covered.

By his own report Bishop told him ‘that Dr Barry was a female and that I was a pretty doctor not to know this and she would not like to be attended by me… that she had examined the body, and Barry was ‘a perfect female’ ‘.

Sophia Bishop also insisted that Barry had given birth when very young. McKinnon inquired as to why she thought so and she pointed to her lower stomach, saying:

‘… from marks here. I am a married woman and the mother of nine children and I ought to know.’

After Barry’s death, her travelling trunk was sold as a curiosity, and the new owner discovered, pasted to the inside of the lid, a collage of fashion plates cut from women’s magazines of the time. Was this significant? Some biographers claim it was, Jeremy Dronfield going so far as to suggest that:

“Here, in this secret shrine, ‘James’ had collected and lovingly, longingly, glued images of all the gowns and bonnets, ribbons and shawls, slippers and coiffures that he had never had the chance to wear.”

Du Preez observes accurately that “Dr Barry is remembered for this sensational fact (that of being a woman) rather than the real contributions she made to improve the health and the lot of the British soldier, as well as civilians”.

Nowhere is the truth of this observation clearer than in some of the recent pieces that have sprung up claiming Barry as transgender, such as ‘Reimagining the Queer Life of Dr. James Barry’ where Jessica Kirwan suggests:

“instead of looking to Barry’s life to reaffirm hegemonic sexual binaries as so many writers have done, Barry’s story should be reclaimed in the promotion of what Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner call queer world-making.”

Did Margaret spend so long – fifty years no less – masquerading as a man that she felt herself to actually be one? Or did she, as Dronfield somewhat romantically suggests, yearn for the gowns and adornments of her time? Did she leave orders that her body should not be examined out of concern for her gender identity, or because she wanted to be remembered for her great work and not ridiculed and mocked by the men who had been her peers?

We will never know the answers to these questions but to claim that Margaret achievements as James were because she actually had a ‘man’s brain’ is absurdly insulting not just to the remarkable woman herself, but to every female who has ever attempted to overcome the confines of a world that tells her ‘no’.

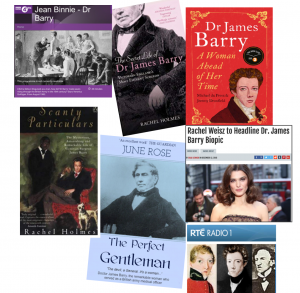

In 1977, June Rose wrote a life of Barry entitled ‘A Perfect Gentleman’. Jeanne Binnie’s radio play ‘Dr Barry’ was first broadcast in 1982. In 2003, Rachel Holmes published ‘Scanty Particulars’ and in 2007 ‘Secret Life of Dr James Barry: Victorian England’s Most Eminent Surgeon’. In 2011, Irish RTE Radio produced a podcast titled ‘Amazing James Barry, The woman who became a man so she could become a doctor’. In 2016 it was announced that a film about Barry would be made by Maven pictures, starring Rachel Weisz in the title role. A YouTube video about Barry has nearly 18,000 hits. Clearly her legacy intrigues people even a hundred and fifty years after her death.

It is only recently that claims that Barry was transgender have arisen. When du Preez and Dromfield’s somewhat romanticised biography ‘A Woman Ahead of her Time’ was first published in 2016, the Guardian printed a review referring to Barry’s life as ‘an exquisite story of scandalous subterfuge’.

It is only recently that claims that Barry was transgender have arisen. When du Preez and Dromfield’s somewhat romanticised biography ‘A Woman Ahead of her Time’ was first published in 2016, the Guardian printed a review referring to Barry’s life as ‘an exquisite story of scandalous subterfuge’.

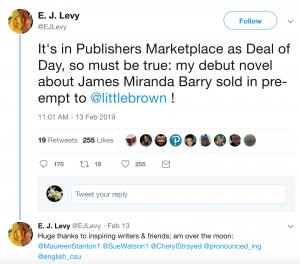

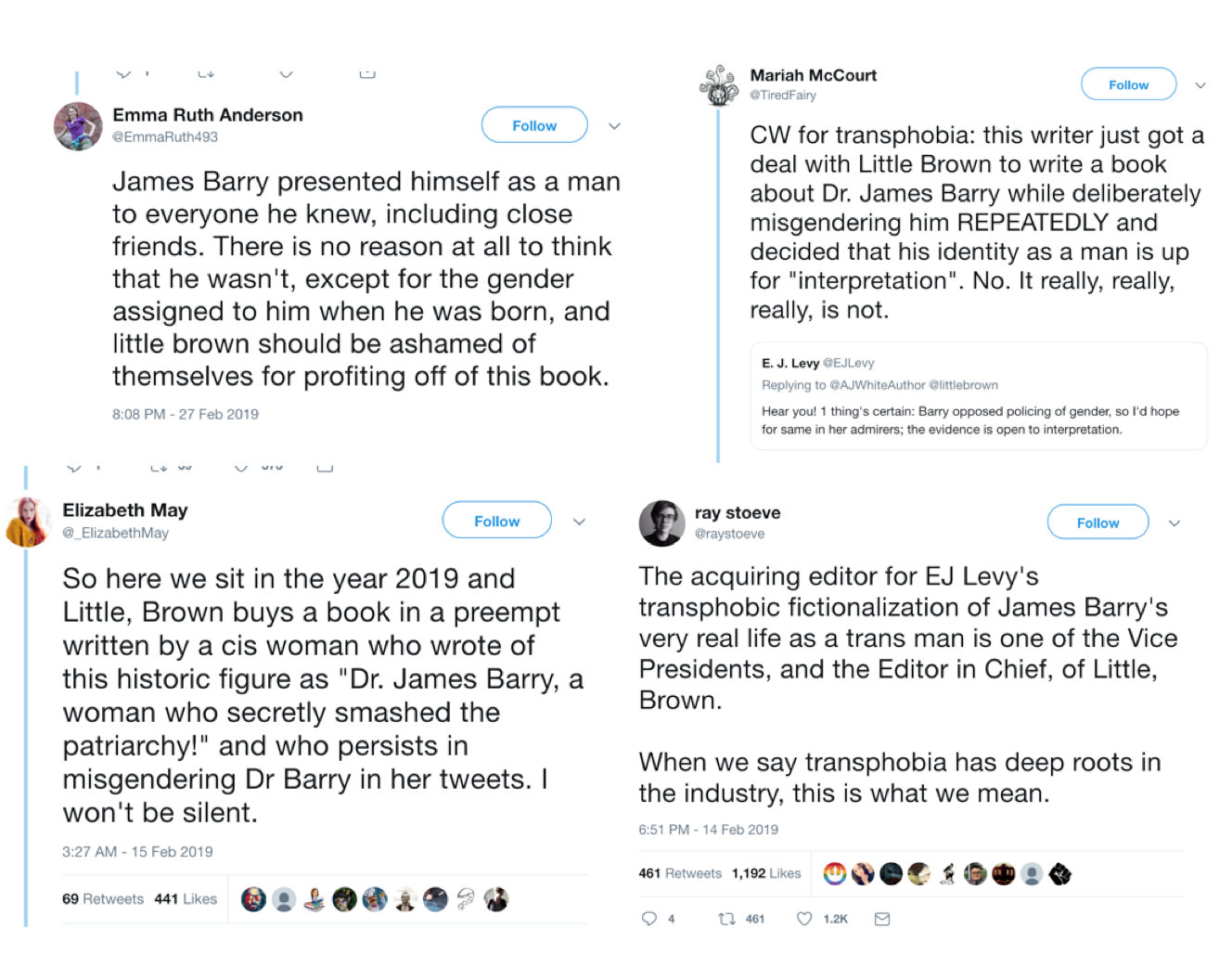

Yet when writer E. J. Levy announced in February 2019 that the publishing house Little, Brown & Co would be publishing her novel about Barry, Twitter recoiled in shock and horror at her use of female pronouns.

Yet when writer E. J. Levy announced in February 2019 that the publishing house Little, Brown & Co would be publishing her novel about Barry, Twitter recoiled in shock and horror at her use of female pronouns.

Calls were made for the publishing house to drop the author, who was accused of ‘undermining transness’ called sickening and transphobic, accused of ‘horrific misgendering’, ‘attacking trans people’ and ‘changing history to suit her own wants’.

A petition was even started to stop publication of the book.

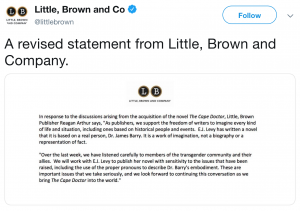

Did Little, Brown & Co rally to support their new author? Did they fuck. Instead, they issued this rather astonishing statement, suggesting that they had ‘listened to the transgender community‘ and that they would ‘work with the author to publish her novel with sensitivity to the issues that have been raised’.’

Did the Guardian write an article defending the author? No, of course not. They wrote this instead.

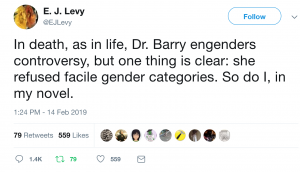

Levy was left to defend herself, which she did with dignity.

The future of Levy’s novel remains to be seen. The lack of support from her publishing house is disappointing but entirely unsurprising. Deceased women who did ‘manly’ things now seem to be fair game for transactivists, and amidst accusations of ‘cis privilege’ and transphobia, feminists, historians and writers are expected to comply with their posthumous transition.

There is an irony in the claim that Levy was ‘changing history for her own wants’. There is little doubt that Barry wished to be remembered as a man. This was made clear in her request that she should be buried in the clothes she died in, without her body being washed. But we don’t get to rewrite history to suit our own wants, or at least we shouldn’t be able to. Fact and fiction may have thin boundaries but they are boundaries none the less. Barry was not a man, nor is there any suggestion that she believed herself to be one.

There seems to be little to support the idea that any of these rebel women believed themselves to be men. While both literature and history have many heroines who lamented that they were not born men, I have not come across one prior to the start of this century who actually genuinely believed herself to be a man.

We need to celebrate these wonderful, wild, inspired, outlier women for what they were – fearless pioneers who refused to be bound by the confines put upon their SEX, not transmen who were able to break boundaries because of their gender identity.

They are our wild women; they are the role models for future generations of young women. We need them.

Our daughters need them.

They were not men.

You can’t have them.

POSTSCRIPT 27/2/19

On 26th March, just two days after I published this article, the Washington Post issued an announcement concerning a Tweet from the day before.

“We’ve deleted this tweet and corrected the podcast episode about Civil War veteran Albert Cashier to remove it from the series about women who won wars and make some corrections to pronoun usage to adhere to Post style.”

Yes, that is correct, the Washington Post no longer recognises Jennie Hodgers as a woman. They have deleted their Tweet about her; removed the podcast about her from a series on women in war and they now refer to her as a man. Hodgers the rebel woman has been erased and replaced with Cashier the transman.

Yes, that is correct, the Washington Post no longer recognises Jennie Hodgers as a woman. They have deleted their Tweet about her; removed the podcast about her from a series on women in war and they now refer to her as a man. Hodgers the rebel woman has been erased and replaced with Cashier the transman.

Here’s a link to Julia Robertson’s article about Jennie/Albert and the Washington Post incident at ‘The Velvet Chronicle’

Thank you Lily

So much information to respond to those being drwan into the Transgender whirlpool and unable to substantiate their concerns.